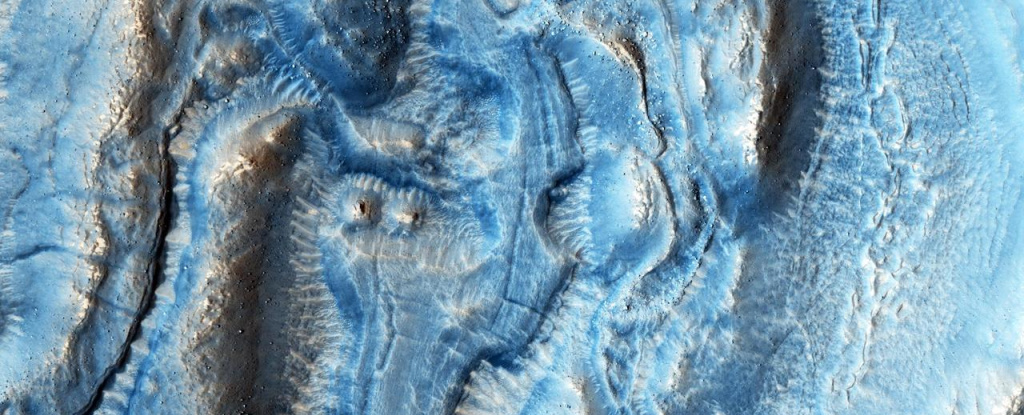

Ancient Glaciers on Mars Flowed So Slowly, We Can Barely Tell They Flowed at All

On Earth, shifts in our climate have caused glaciers to advance and recede throughout our geological history (known as glacial and inter-glacial periods).

The movement of these glaciers has carved features on the surface, including U-shaped valleys, hanging valleys, and fjords. These features are missing on Mars, leading scientists to conclude that any glaciers on its surface in the distant past were stationary.

However, new research by a team of the US and French planetary scientists suggests that Martian glaciers did move more slowly than those on Earth. The research was conducted by a team of geologists and planetary scientists from the School of Earth and Space Exploration (SESE) at Arizona State University (ASU) and the Laboratorie du Planétologie et Géosciences (LPG) at Nantes Université in France.

The study was led by Anna Grau Galofre, a 2018 Exploration Fellow with the SESE (currently at the LPG), who was a postdoc at ASU when it was conducted.

The study, titled “Valley Networks and the Record of Glaciation on Ancient Mars,” recently appeared in the Geophysical Research Letters.

According to the USGS definition, a glacier is “a large, perennial accumulation of crystalline ice, snow, rock, sediment, and often liquid water that originates on land and moves downslope under the influence of its own weight and gravity.”

The key word here is moves, resulting from meltwater gathering below the ice sheet and lubricating its passage downwards across the landscape. On Earth, glaciers have advanced and regularly retreated for eons, leaving boulders and debris in their wake and carving features into the surface.

For the sake of their study, Grau Galofre and her colleagues modelled how Martian gravity would affect the feedback between how fast an ice sheet moves and how water drains below it. Faster water drainage would increase friction between the rock and ice, leaving under-ice channels that would likely persist over time.

The absence of these U-shaped valleys means that ice sheets on Mars likely moved and eroded the ground under them at extremely slow rates compared to what occurs on Earth.

However, scientists have found other geologic traces that suggest that there was glacial activity on Mars in the past. These include long, narrow, winding ridges composed of stratified sand and gravel (eskers) and other features that could be the result of subglacial channels.

Said Grau Galofre in a recent AGUNews press release:

“Ice is incredibly non-linear. The feedback relating to glacial motion, glacial drainage, and glacial erosion would result in fundamentally different landscapes related to the presence of water under former ice sheets on Earth and Mars.

Whereas on Earth you would get drumlins, lineations, scouring marks and moraines, on Mars you would tend to get channels and esker ridges under an ice sheet of exactly the same characteristics.”

To determine if Mars experienced glacial activity in the past, Grau Galofre and her colleagues modelled the dynamics of two ice sheets on Earth and Mars that had the same thickness, temperature, and subglacial water availability.

They then adapted the physical framework and ice flow dynamics that describe water drainage under Earth’s sheets to Martian conditions. From this, they learned how subglacial drainage would evolve on Mars, what effects this would have on the velocity at which glaciers slid across the landscape, and the erosion this would cause.

These findings demonstrate how glacial ice on Mars would drain meltwater much more efficiently than glaciers on Earth. This would largely prevent lubrication at the base of the ice sheets, which would lead to faster sliding rates and enhanced glacial-driven erosion.

In short, their study demonstrated that lineated landforms on Earth associated with glacial activity would not have had time to develop on Mars.

Said Grau Galofre:

“Going from an early Mars with presence of surface liquid water, extensive ice sheets and volcanism into the global cryosphere that Mars currently is, the interaction between ice masses and basal water must have occurred at some point.

It is just very hard to believe that throughout 4 billion years of planetary history, Mars never developed the conditions to grow ice sheets with presence of subglacial water, since it is a planet with extensive water inventory, large topographic variations, presence of both liquid and frozen water, volcanism, [and is] situated further from the Sun than Earth.”

In addition to explaining why Mars lacks certain glacial features, the work also has implications for the possibility of life on Mars and whether that life could survive the transition to the global cryosphere we see today.

According to the authors, an ice sheet could provide a steady water supply, protection, and stability to any subglacial bodies of water where life could have emerged. They would also protect against solar and cosmic radiation (in the absence of a magnetic field) and insulation against extreme variations in temperature.

These findings are part of a growing body of evidence that life existed on Mars and survived long enough to leave evidence of its existence behind. It also indicates that missions like Curiosity and Perseverance, which will be joined by the ESA’s Rosalind Franklin rover and other robotic explorers in the near future, are searching in the right places.

Where water once flowed in the presence of slowly-retreating glaciers, microbial life forms that emerged when Mars was warm and wet (ca. 4 billion years ago) might have persisted as the planet became colder and desiccated. These findings may also bolster speculation that as this transition progressed and much of Mars’ surface water retreated underground, potential life on the surface followed.

As such, future missions investigating Mars’ extensive deposits of aqueous minerals (recently mapped out by the ESA) could be the ones that finally find evidence of present-day life on Mars!