Guatemalan family uncovers ancient Mayan murals on their kitchen walls during a home renovation

Home renovations in a Guatemalan mountain village in 2003 unearthed “unparalleled” Maya murals, according to researchers. Now, reports broadcast network RT, a new analysis published in the journal Antiquity has revealed additional insights on the wall paintings, which date to the 17th or 18th century and blend Spanish colonial influences with local indigenous culture.

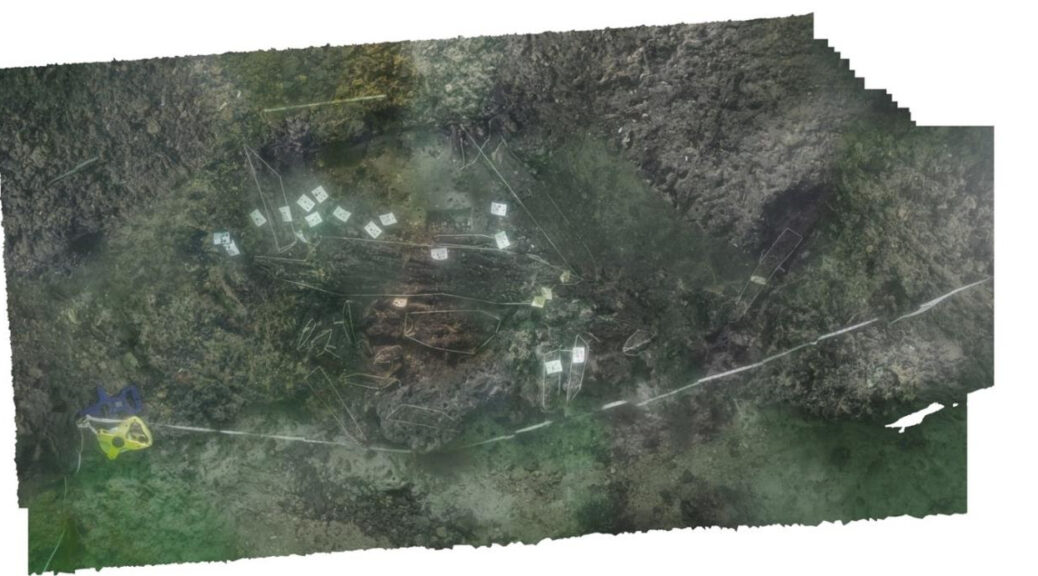

Local historian and study co-author Lucas Asicona Ramírez found the murals while renovating his kitchen in Chajul, a rural town in Guatemala’s highlands, reported Mike McDonald for Reuters in 2012.

Several houses in Chajul, including Asicona’s, date to the colonial era (1524 to 1821); other locals have discovered similarly historic artworks behind the plaster in their homes.

The majority of Guatemala’s colonial-era murals are found in houses of worship. Centered on Christian themes, these religious artworks were used by the Spanish to assert their dominance over the Maya people, writes Tom Fish for Express. In contrast, the Chajul wall paintings appear inside private homes—and, most tellingly, contain distinct flourishes of indigenous culture.

“We consider these murals to be very unique,” Ivonne Putzeys, an archaeologist at the University of Guatemala in San Carlos, told Reuters. “It’s a tangible heritage that represents [s] real scenes from history.”

In 2015, an international team of researchers started preserving and studying the murals in collaboration with a Maya community indigenous to Guatemala: the Ixil. This group formed the bulk of the roughly 200,000 people killed during the Guatemalan Civil War, which lasted from 1960 to 1996.

As the experts write in the paper, conducting interviews and consultations with the Ixil was essential to understanding the art’s cultural context.

Many of the friezes feature dancers and musicians. Jaroslaw Źrałka, an archaeologist at Jagiellonian University and first author of the new study, tells Ancient Origins’ Ed Whelan that dance played an important role in the Maya civilization, both recording and relaying history and cultural practices. The dance was so important to the Maya that Spanish missionaries used it as a conversion tool, says Źrałka.

Through interviews with the Chajul Ixil community, the researchers were able to identify specific murals as depictions of known dances from the colonial era.

One mural shows tall, bearded conquistadors playing drums as they encounter a dancer dressed in a traditional feathered costume. This scene may illustrate the Dance of the Conquest, which details Spain’s invasion and attempts to convert the Maya to Christianity.

Another mural may show the Dance of the Moors and the Christians. Introduced by the Spaniards, this performance tells the story of Spain’s seizure of lands occupied by Muslim kingdoms, according to Express.

The researchers note that the wall art may also feature dances now lost to history. Many were forgotten when the government prohibited the performance of indigenous dances in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Chemical analysis of the paintings revealed the use of natural clay pigments typical in Maya art, suggesting the murals were indeed created by indigenous artists, reports Ancient Origins. The artworks’ style hews closely to local traditions, showing few signs of foreign influences.

The researchers suggest that the houses in which the murals were found once belonged to key community members—perhaps members of what was known as the cofradías, or brotherhood.

These groups organized religious events connected to both Christian and pre-Hispanic Maya traditions. The houses featuring the friezes may have served as meeting places or venues for rituals and dances.

Per the paper, the murals’ blending of Maya and European imagery could mean that local culture, as revived by the cofradías, was making a defiant comeback as Spain’s influence and control over the region faded.