Archeologists discover 2000-year-old Roman coins on the deserted Swedish island of Gotska Sandön

Archaeologists found 2,000-year-old Roman coins on the Swedish deserted island of Gotska Sandön.

Previously, ancient Roman coins were discovered on the Swedish island of Gotland. Finding similar ancient items on the deserted island of Gotska Sandön, on the other hand, is unusual. Because of its location, it is a unique discovery.

The coins stem from the time of Emperor Trajan, who ruled the Roman Empire in the years 98-117, and Antoninus Pius, who ruled between 138 and 161.

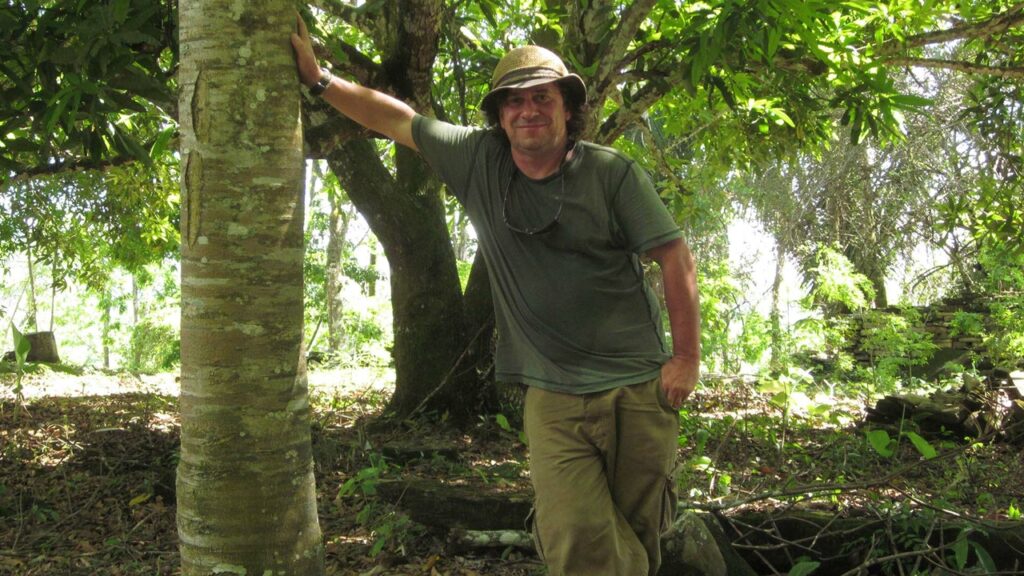

The discovery was made by a team of experts from Södertörn University and the Gotland Museum.

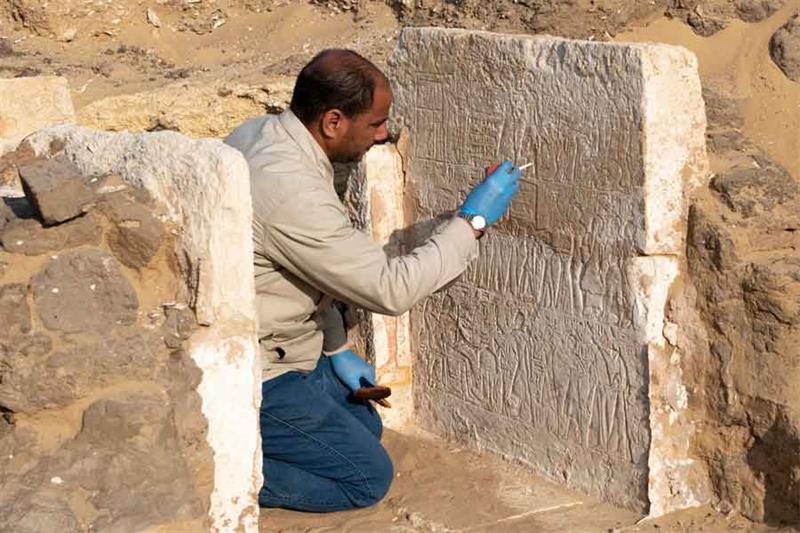

Archaeologists, to this day, have not been able to identify the historical role of the island within the Baltic region’s different historical eras. The island has been inhabited since the Stone Ages, as seal bones, slaughter remains from cows, and a battle glove was previously excavated.

In a statement, Johan Rönnby, professor of marine archeology at Soderon University, which runs the excavations in collaboration with the Gotland Museum, stated that “These are exciting finds that raise several questions.”

Archaeologists are now debating whether the discoveries are shipwreck remains strewn across the beach. A large number of hearths and fireplace remains have been discovered along the island’s coast. Another theory is that the coins are somehow related to these activities.

A local lighthouse keeper claimed to have discovered a Roman coin on the island in the late 1800s, which was met with skepticism. The recent discoveries may vindicate him.

“Finds of Roman silver coins are not unusual for Gotland, but are for Gotska Sandon. What makes this find interesting is precisely the location,” Daniel Langhammer of the Administrative Board in Gotland County said.

Gotland, Sweden’s largest island and a key point in the Baltic Sea maritime trade, is rich in medieval treasures.

The number of Arab dirhams discovered on the island, in particular, is astounding, dwarfing any other site in Western Eurasia. These coins made their way north along the Silver-Fur Road through trade between Rus merchants and the Abbasid Caliphate.

The 9-km long and 6-km wide Gotska Sandon island is part of Gotland County and has been a national park since 1909.