How did the ancient Egyptians drill through granite?

A question that has always intrigued archaeologists is how past civilizations made their objects and monuments. Works such as the exquisite staircases of Machu Picchu, the geoglyphs of Acre, and the pyramids of Egypt raise questions about the use of technologies and tools.

The lack of understanding usually leaves room for hypotheses about contact with aliens or the idea that these people were beyond their time; dangerous arguments when it comes to a faithful understanding of the past.

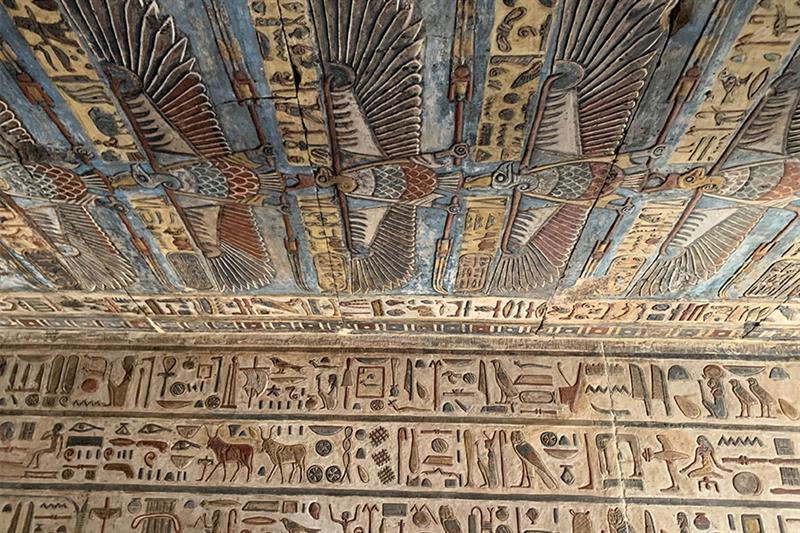

The ancient Egyptians, known for their temples, pyramids, and hieroglyphic writing, have always been a challenge for researchers.

And a skill that still intrigues many people is the ability to carve objects in granite – rock much harder than limestone or sandstone.

So, what tools did they have to hand? How long did the carving process take? Had they been helped by fantastic beings? Check out some of the possibilities below.

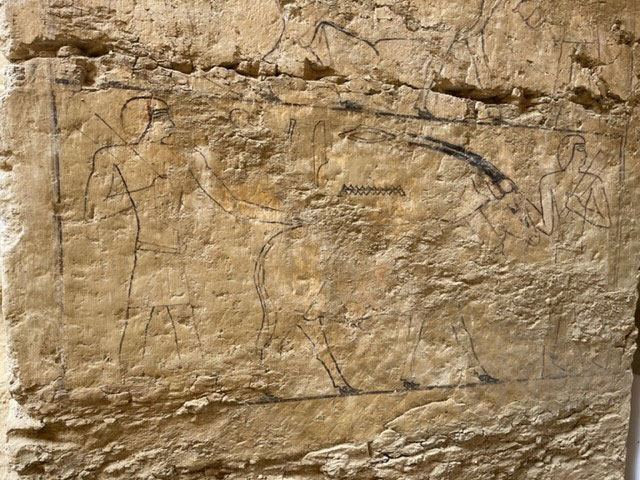

Egyptian artisans, the working class responsible for all the grandeur that has come to us, used instruments depicted in paintings that resisted time, showing the use of axes, saws, and bows, among others.

The most accepted theory is that these builders used wooden, bronze, and copper tools to carve the granite, mastering strict rules that allowed a good job.

Around 3500 BC, many copper tools were used, adding to the skills of the artisans, which made it possible to carry out any and all work with accuracy.

But would wooden tools be enough to carve granite? That was the main question during the nineteenth century when archaeologists came across artefacts like these.

Only later studies, not focusing on the objects themselves but on the way in which they were used, came closer to a solution.

Methods

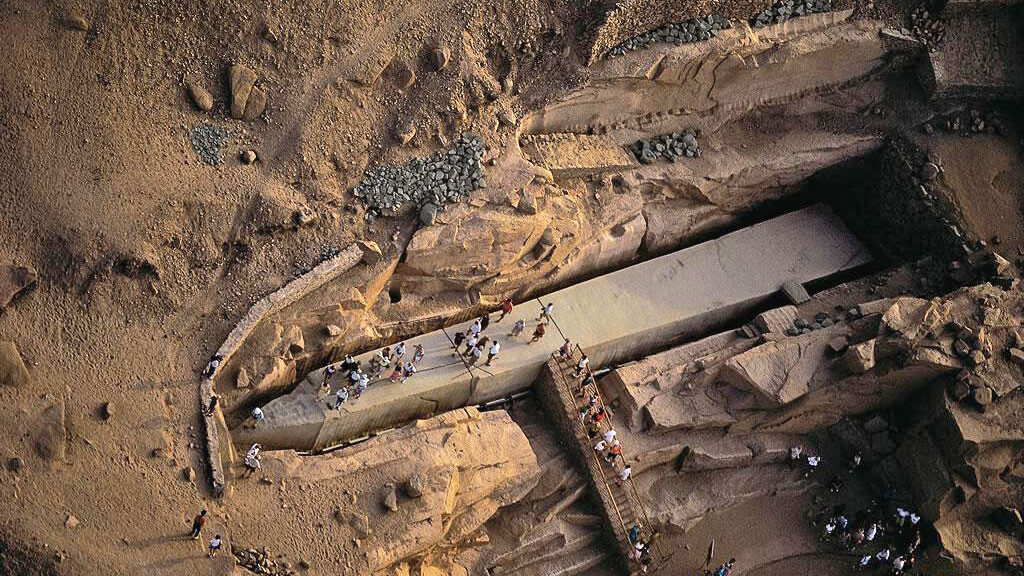

According to current archaeology, the ancient Egyptians drilled granite with a method that consisted of introducing wooden wedges into a natural crack in the rock and soaking them with water. As the wet wood expanded, the original crack widened, and after successive repetitions of the process, the rock split into smaller pieces.

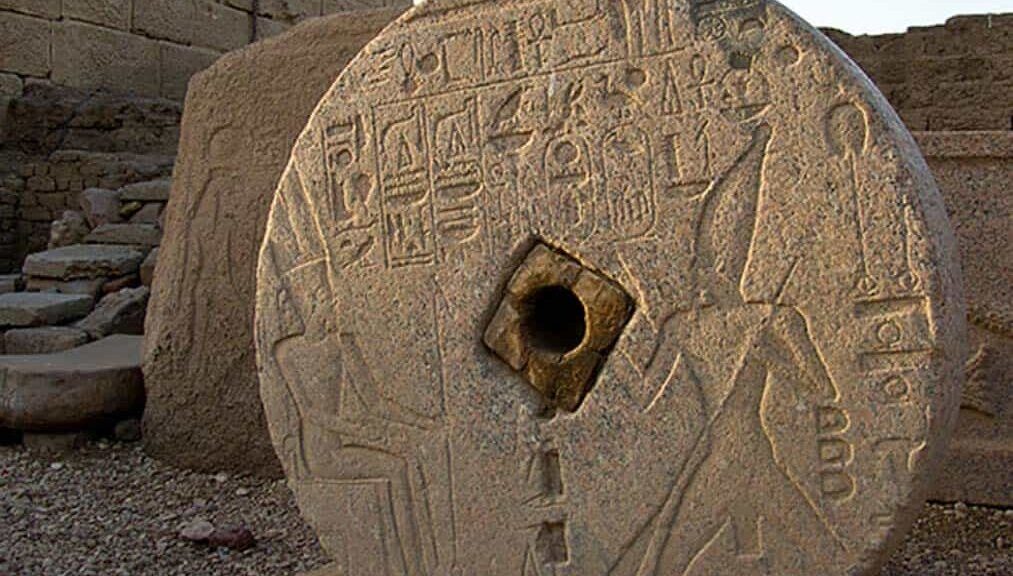

Stone artisans, ancient and modern, use this natural process based on weaker parts of the rock. Another method used was successive incisions in the stone with metal objects, which, little by little, carved lines and designs, intervening in different ways in the rock.

However, such methods do not seem to explain everything. The English engineer, Christopher Dunn, is one of the great promoters of these issues, and since 1977, he has been questioning himself about the use of technologies in Ancient Egypt.

Talking to Egyptologists and visiting sites, Dunn was not convinced by the wedge and water method alone.

According to him, “the quarry marks I saw did not convince me that the methods described were the only means by which the builders of the pyramids worked their rocks.”

The tools displayed as instruments for creating many artefacts are physically incapable of being reproduced. For the engineer, the artefacts would only have reached such a degree of precision with the use of saw blades and objects with a hardness comparable to that of a diamond.

Discussions like these are still current, and perhaps Egyptologists have yet to find tools that better explain the construction of these objects.

But what we must keep in mind is that maybe we are the limited ones, relying too much on our own technologies and applying contemporary ways of seeing the world to the past.