The most dangerous place on Earth 100 million years ago

The world feels like a scary place these days, but a recently published paleontology study helps put things in perspective. A review of 100 years of fossil evidence reveals that 100 million years ago a portion of the Sahara Desert was arguably the most dangerous place on the planet, with a concentration of large predatory dinosaurs unmatched in any comparable modern terrestrial ecosystem.

The analysis of fossils from the so-called Kem Kem beds — rock formations in southeastern Morocco, near the Algerian border, dating back to the Cretaceous period — shows the presence in the area of large scale carnivorous dinosaurs, flying predatory reptiles, and crocodile-like hunters, all living together in what was at the time a river system full of very large fish, rather than a desert.

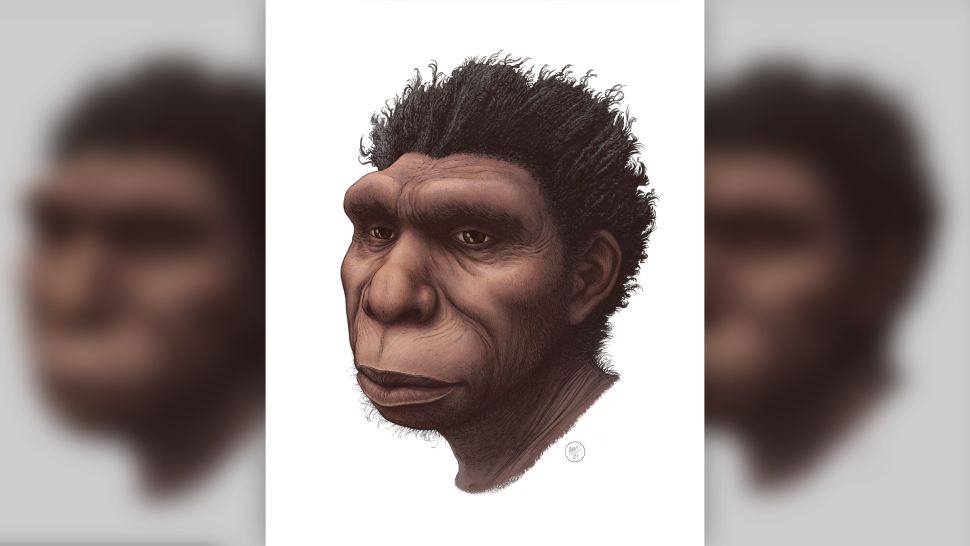

The creatures found in the Kem Kem beds roamed the Earth some 95 million years before early humans appeared on the planet, but “if you had a time machine and could travel to this place, you probably wouldn’t last very long,” said palaeontologist Nizar Ibrahim, lead author of the study.

Ibrahim told CNN that the Kem Kem ecosystem was “a really mysterious place, ecologically speaking,” since typical ecosystems present a larger number of plant-eating animals than predators, and predators themselves will come in a variety of sizes, with one larger predator being dominant.

In the Kem Kem, fossils of predators outnumber those of plant-eating dinosaurs, and several of the predators living together in the area, such as the Carcharodontosaurus, the Spinosaurus, the Abelisaur and the Deltadromeus, were as big as a Tyrannosaurus rex.

This is unusual “even for dinosaur standards,” according to Ibrahim, since the T. rex, which was present in North America tens of millions of years later, was “the undisputed ruler of its ancient ecosystem.”

An abelisaur, a predatory dinosaur, rests while several pterosaurs fight over leftovers from a carcass. Artwork by Davide Bonadonna, under the scientific supervision of Simone Maganuco and Nizar Ibrahim.

It is unlikely that the large predators in the Kem Kem ate one another.

What’s more realistic, according to Ibrahim, is that they ate the abundant and supersized fish present in the area — fish like coelacanths “the size of a car” and sawfish that could reach 25 feet in length.

What did some of the large predators in the Kem Kem ecosystem look like?

Matthew Lamanna, a palaeontologist and the principal dinosaur researcher at Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, said the meat-eating Carcharodontosaurus would resemble a Tyrannosaurus rex in shape and size, but “with a proportionally narrower head, somewhat longer arms, and three fingers (rather than two) on each hand.”

The even larger Spinosaurus would look somewhat like “the unholy love child of Carcharodontosaurus and a crocodile,” said Lamanna, with a crocodile-like skull and teeth and a body that is a mix of both, but with longer forelimbs. A fish-eating water creature, the Spinosaurus’ most distinctive feature is “a six-foot-tall sail running the length of its back.”

The Abelisaur would be smaller than a Spinosaurus, and “vaguely bulldog-faced,” according to Lamanna.

The Deltadromeus, known only from an incomplete skeleton, was also presumably similar in size to a T. rex, said Lamanna. According to Ibrahim, the Deltadromeus presents very slender proportions in its legs and a very long tail, and it remains mysterious in the absence of fossil evidence of its neck and skull.

Among the other species present in the Kem Kem were “predatory crocodiles that would be at least as big as any that are alive today” and flying reptiles like Pterosaurs “that would dwarf any modern flying bird,” Lamanna told CNN.

The study of the Kem Kem beds carried out by Ibrahim and a group of international researchers across the US, UK, Europe and Africa draws attention to the importance of learning more about the palaeontology of Africa, among other areas of the Southern Hemisphere.

Forgotten continent

“Africa, in many ways, remains palaeontology’s forgotten continent,” said Ibrahim, and this study “addresses this bias.” Even though the accessibility of evidence and its degree of preservation in the African continent varies widely, there remains so much more to be discovered in Africa.

What the Kem Kem research shows is that African ecosystems “do not simply replicate the ones we know from North America, or Europe, or other better-known places,” and it also reveals clues about what happens to life when dramatic changes in climate come into play.

Evidence in the rock layers in the Kem Kem Group shows that the river system where predators and large fish thrived eventually became flooded with seawater, turning the area into a warm, shallow sea. Fast forward to today and that same area is in the largest hot desert in the world.

Palaeontology can help us understand “the long term consequences of biodiversity loss, which we are experiencing right now,” said Ibrahim.