Medieval Church Excavated in Sudan’s Northern State

Science in Poland reports that researchers led by Artur Obłuski of the University of Warsaw have found the remains of a large medieval church in the centre of Old Dongola, Northern State, Sudan.

According to, Assist. Prof. Artur Obłuski, the head of the Dongola expedition and the director of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw (PCMA UW), this discovery changes not only our knowledge about the city itself but also the way we reconstruct the history of the Nubian church.

Dongola was the capital of Makuria, one of the three Christian Nubian kingdoms. Archaeologists from PCMA UW have been working there since 1964, continuing the research initiated by Prof. K. Michałowski after the success of his work in another Nubian centre – Faras, the capital of Nobadia.

Since 2018, work in Dongola has been carried out under the European Research Council (ERC) grant “UMMA – Urban Metamorphosis of the community of a Medieval African capital city”, headed by Assist. Prof. Obłuski.

In 2021, archaeologists cleaned the wall of the church’s apse, together with an adjacent wall and the nearby dome of a large tomb. The structures are located in the very centre of the city.

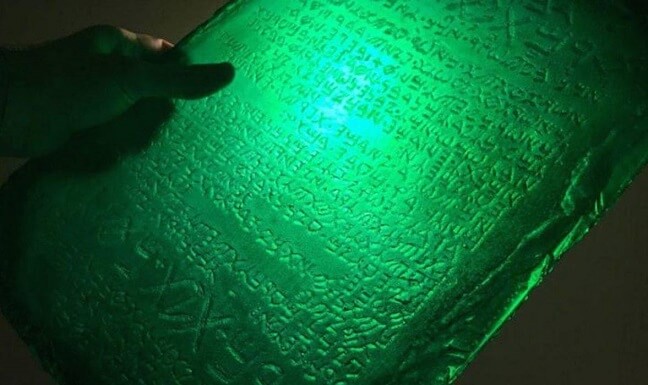

The walls of the apse, which was the most sacred place in the church, are decorated with paintings depicting two rows of monumental figures. It is the largest apse so far discovered in Nubia: it has a diameter of 6 m, and the width of the church to which it belonged is approx. 26 m.

“If our estimates based on the known dimensions are confirmed, it is the largest church discovered so far in Nubia,” – says Obłuski, adding – “Its size is important, but so is the location of the building – in the heart of the 200-hectare city, the capital of the combined kingdoms of Nobadia and Makuria. Just to the east of the apse, a large domed building was added.

We have a great analogy for such an architectural complex: Faras. There too, the cathedral stood in the centre of the citadel, and to the east of it was the domed tomb of Joannes, the bishop of Faras. However, there is a major difference in the scale of the buildings. The dome over Joannes’ tomb is 1.5 m in diameter, while the dome over the Dongolese building is 7.5 m.”

Archaeologists assume that, just like in Faras, the large church in Dongola served as a cathedral, next to which a tomb of dignitaries, probably bishops, was erected. The confirmation of this hypothesis will have significant consequences for Nubiology.

Until now, another church located outside the citadel was considered to be Dongola’s cathedral, a building whose features would influence the religious architecture of Nubia over the centuries. “If we are right, it was a completely different building that set the trends,” – says Obłuski.

The newly discovered building stands in the middle of the citadel that is surrounded by a wall about 10 m high and 5 m thick.

The excavations have shown that this was the heart of the entire kingdom in the Makurian period as all structures uncovered there were of a monumental character: churches, a palace, and large villas belonging to a church and state elites. Test trenches dug in the building have yielded promising results.

“The sounding in the apse is approx. 9 m deep. This means that the eastern part of the building is preserved to the impressive height of a modern three-storey block of flats. And this means there may be more paintings and inscriptions under our feet, just like in Faras,” – says the archaeologist.

Therefore, among the team members are conservators from the Department of Conservation and Restoration of Works of Art of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, working under the supervision of Prof. Krzysztof Chmielewski. Their immediate task is to secure the discovered paintings on an ongoing basis, and in the long term, to prepare them for display. Unlike at Faras, they can be left on the church walls.

“In order to continue the excavations, the weakened and peeling wall plaster covered with painting decoration must be strengthened, and then carefully cleaned of layers of earth, dirt and salt deposits that are particularly harmful to the wall paintings.

See Also: MORE ARCHAEOLOGY NEWS

When a suitable roof is erected over this valuable find, it will be possible to start the final aesthetic conservation of the paintings,” – explains Prof. Chmielewski, adding that this type of rescue conservation requires the involvement of considerable resources, time, and skilled specialists.

The next excavation seasons in Dongola are planned for the fall of this year and the winter of 2022.