A 4,000-Year-Old Writing system that finally makes sense to Scholars

You could be forgiven for never having heard of the civilization of Elam. Elam flourished in southern Iran, in the modern state of Khuzestan, about four or five thousand years ago. The Elamites had close cultural ties to the Mesopotamian civilizations to the west, like the Babylonians; they built ziggurats, for instance (via Britannica).

They had a number of unique customs, though, including royal succession, and possibly property rights being passed down matrilinearly, from mothers to sons (instead of fathers to sons), which suggests that Elamite women enjoyed a degree of importance. The Elamites were eventually swallowed up by other cultures, and their capital, Susa, would become the home of the kings of Persia.

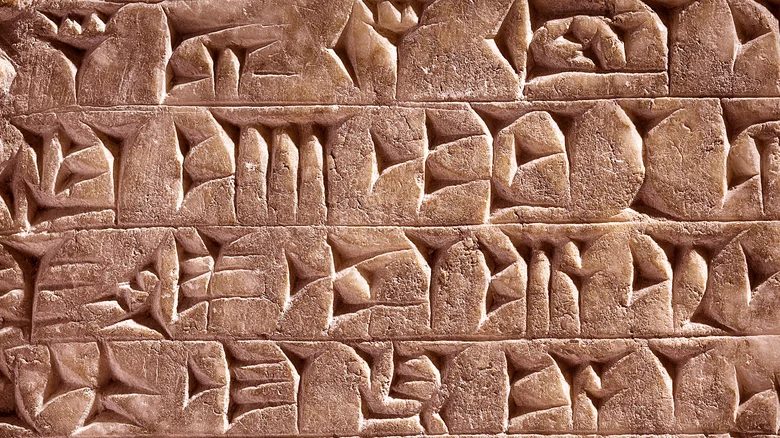

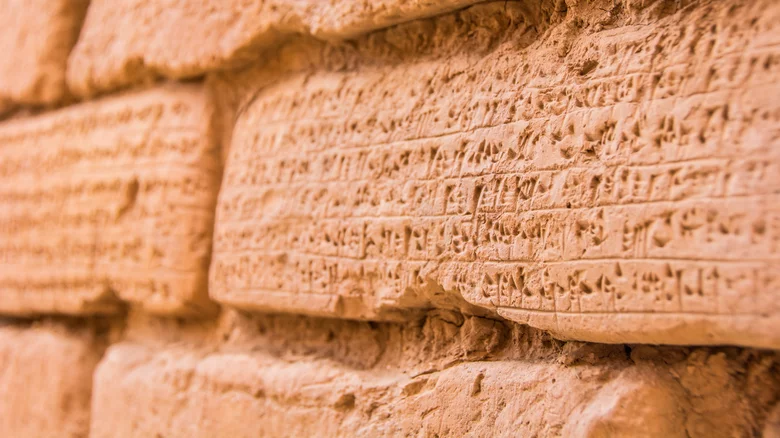

But what vexed archaeologists and philologists for centuries was the Elamite language. They simply couldn’t read it. According to Smithsonian, the earliest Elamite script looked like Mesopotamian cuneiform, but no one could quite decode it.

LINEAR ELAMITE

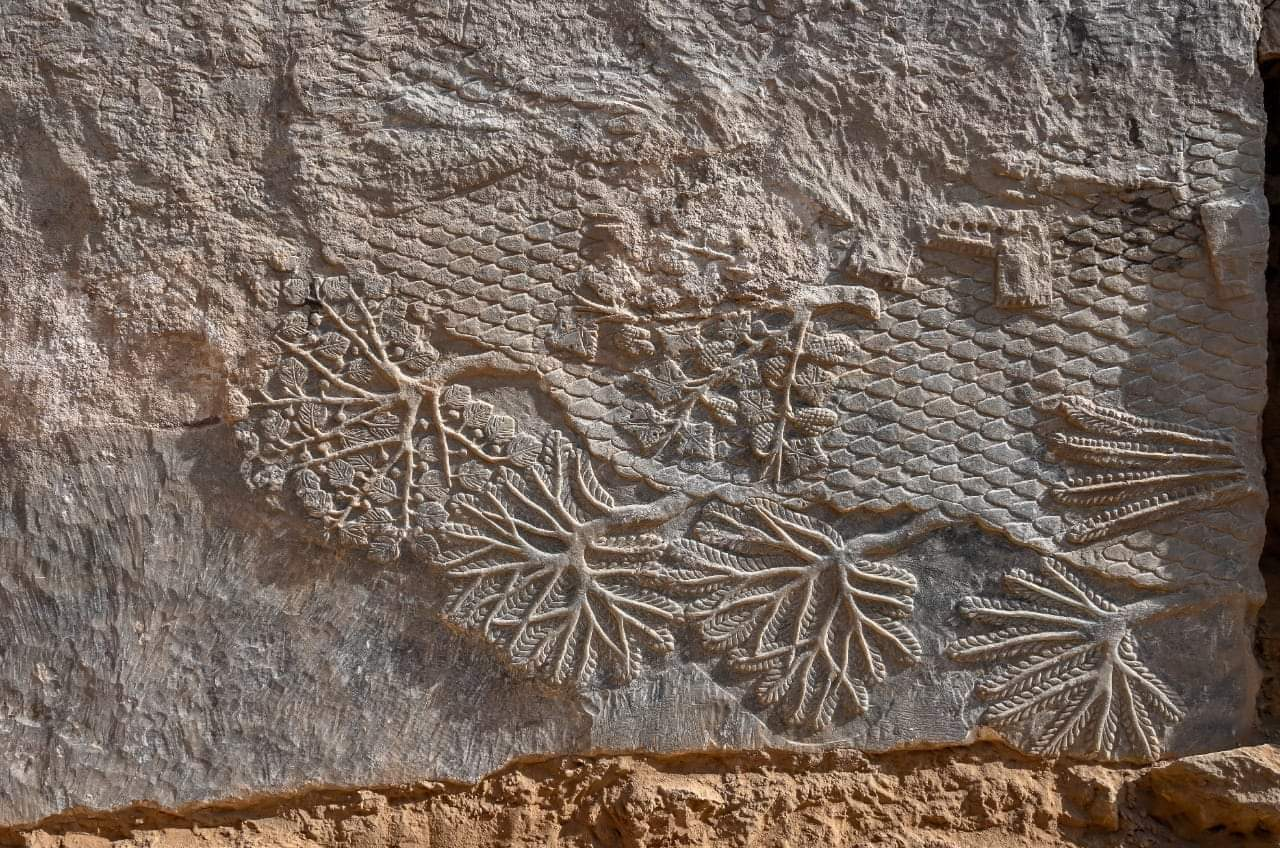

Smithsonian notes that only 43 examples of this early script, called Linear Elamite, have ever been discovered. It had fallen out of use by about 1800 B.C., replaced by western forms of cuneiform and then by Greek. It wasn’t clear whether the words expressed or depicted by Linear Elamite were words of the same language as the later, readable texts. Perhaps it was a different language altogether.

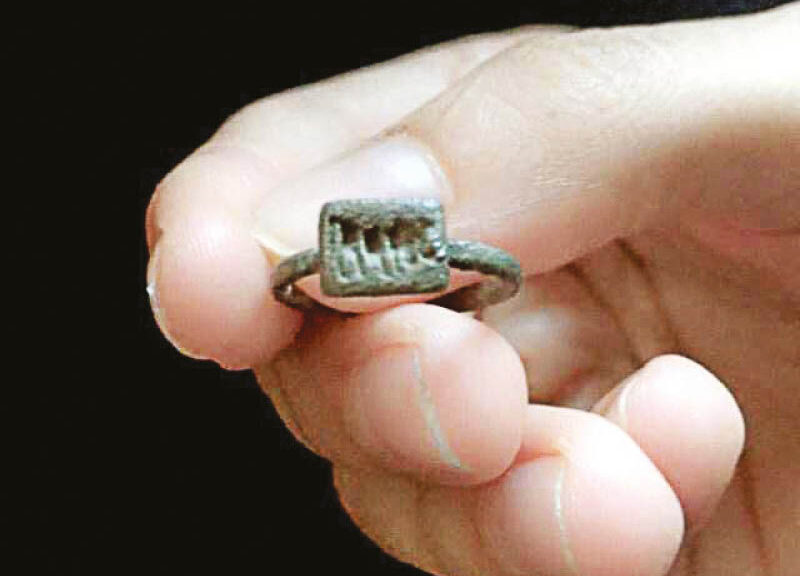

In 2015 came a breakthrough. A certain François Desset, professor of archaeology at the University of Teheran, was curious about the inscriptions on a collection of silver beakers once thought to be a hoax to fleece collectors, but recently confirmed as genuine.

On many of them, he found two parallel inscriptions: one in the familiar Elamite language, and another in Linear Elamite. He had found the key to the puzzle.

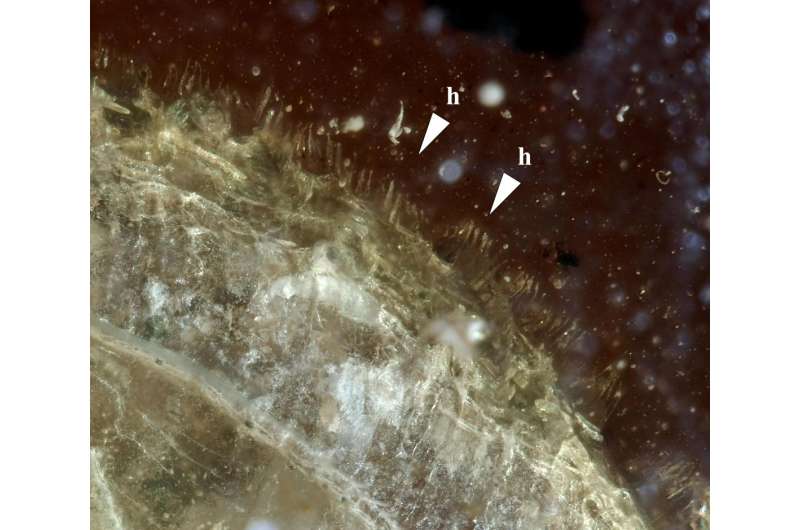

The Linear characters were pictograms, rather than alphabetical letters, which made them hard to translate, but Desset guessed from the context that some of them stood for names. Slowly the language revealed its secrets. Desset would translate 72 Linear characters, leaving only a handful still unclear.

LIKE THE ROSETTA STONE

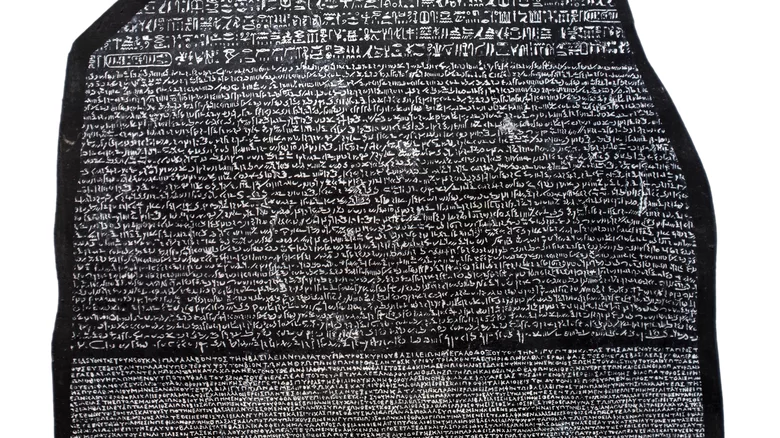

Desset’s work bears a remarkable resemblance to the translation of the Rosetta Stone.

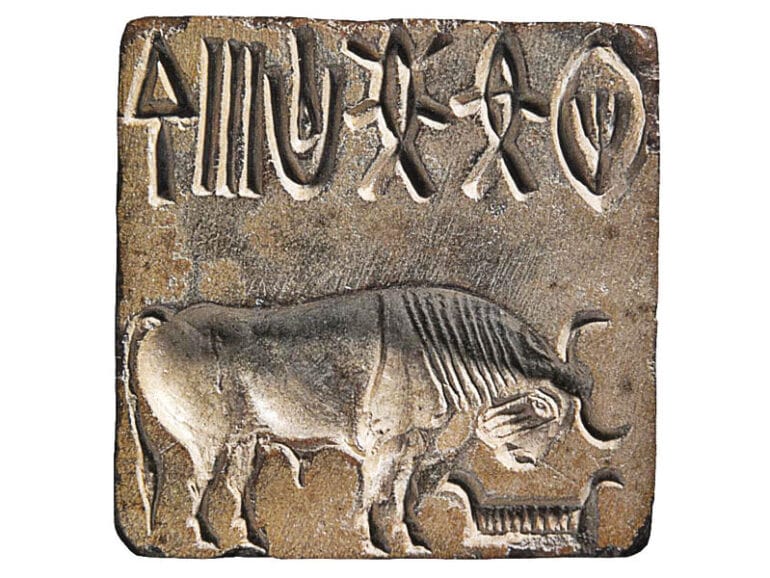

The first archaeologists could not decipher Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, with their suns and birds and abstract shapes instead of letters. But when Napoleon invaded Egypt, his men found a tablet inscribed with three languages (shown above) in the Nile mud near the town of Rosetta.

According to the British Museum, this was one of many “mass-produced” tablets from the year 196 B.C., a kind of public bulletin. It repeated the same message in three kinds of script: hieroglyphics, “demotic” Egyptian, and Greek.

A Frenchman named Champollion realized that the names of non-Egyptian people were recognizable in the jumble of hieroglyphics. Slowly, he began to pair Greek words and phrases with ancient Egyptian ones, eventually unravelling the code.

It is remarkable that another Frenchman, 200 years later, should use exactly the same method to decode Linear Elamite: recognizing names in the band of script and deducing the rest from there.