Vase Kept In Kitchen Turned Out To Be 250-Year-Old Relic, Auctioned For 1.5 Million Pounds

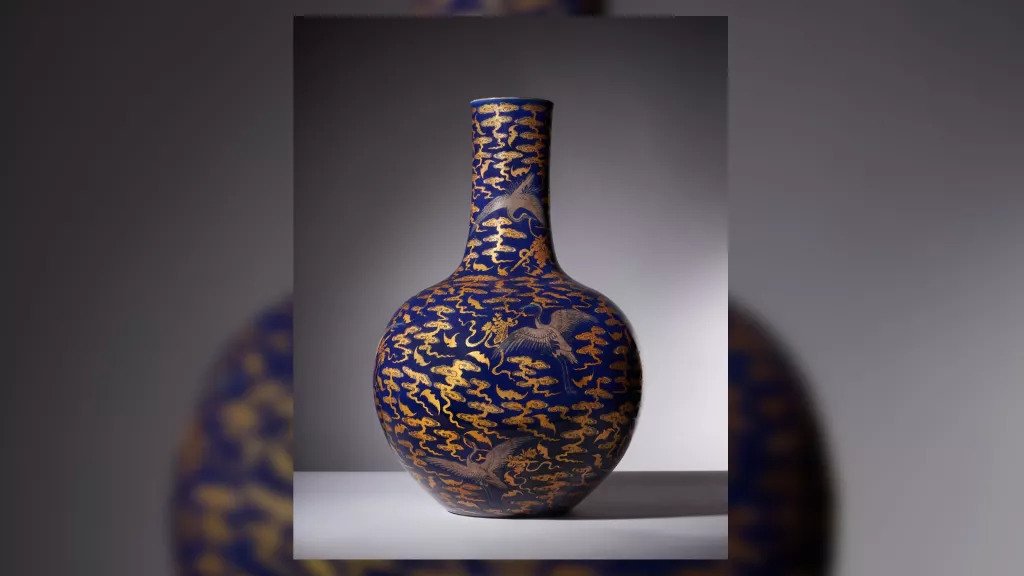

A royal blue 18th-century Chinese vase decorated with gold and silver, which sat in a U.K. kitchen for several years, just sold at auction for about $1.8 million after historians realized it had once belonged to an emperor.

However, the vase’s unclear history — combined with the looting of Chinese palaces in the 19th century — raises ethical concerns, according to an expert who was not involved with the sale.

The vase is large, about 2 feet (0.6 meters) tall, and it is marked with a symbol associated with the Qianlong emperor — the sixth emperor of the Qing dynasty, the country’s last imperial dynasty — who ruled China from 1735 to 1795, according to a statement released by the auction company Dreweatts, which sold the vase on May 18.

The vase is painted with a colour called “sacrificial blue” — so named because the same shade decorates parts of the Temple of Heaven in Beijing.

At this temple, the emperor of China would sacrifice animals in hopes that these sacrifices would ensure a good harvest.

The decorations on the vase are made of a mix of silver and gold, and they depict clouds, cranes, fans, flutes and bats — symbols of the emperor’s Daoist beliefs that are associated with a good and long life, said Mark Newstead, a specialist consultant for Asian ceramics and works of art with Dreweatts, said in a YouTube video.

The combination of silver and gold used on this vase is “technically very difficult to achieve and that’s what makes it so special and unusual,” Newstead said, noting that a man named Tang Ying (1682-1756), who was the supervisor of an imperial porcelain factory in the eastern city of Jingdezhen, is sometimes credited with the creation of the technique used on this vase.

This vase would likely have been placed in the Forbidden Palace — where the Chinese emperor resided — or in one of the emperor’s other palaces, Newstead said.

During the Qianlong emperor’s rule, the government had to put down a number of rebellions. Despite this unrest, the arts flourished in China, wrote historian Richard Smith in the book “The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture(opens in new tab)” (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2015).

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the political situation worsened as China lost a number of wars against Europe and America, and foreign troops looted a number of palaces.

Uncertain origins

Much about the history of this vase is unknown. The vase was owned by a surgeon who “we believe bought it in the early 1980s,” Newstead told Live Science in an email.

The surgeon “was a buyer in the country salerooms in the [English] Midlands from the 1970s onwards and that is all we know,” Newstead said. After the surgeon died, the vase was passed on to his son. Neither the surgeon nor the son realized the true value and the vase was placed in the son’s kitchen for some time, and Newstead first saw it in the late 1990s.

The vase’s unclear origins and the history of foreign troops looting palaces in the 19th century raise some ethical concerns that the vase was plundered by foreign troops in the 19th or early 20th century, an expert told Live Science.

“It could have been a gift from the emperor to one of his officials, and that official’s family could have sold it on the open market in the 20th century when they fell on hard economic times. And from there it would have been sold many more times. Or, it could be the product of the military plunder of 1860 or 1901, which would make its auction much more morally dubious,” Justin Jacobs, a history professor at American University in Washington, D.C., told Live Science in an email.

Jacobs has studied and written extensively about the pillaging of Chinese art in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

“We just don’t know [how the vase left China] and likely we never will,” Jacobs said.