Hominin Bone in Israel Dated to 1.5 Million Years Ago

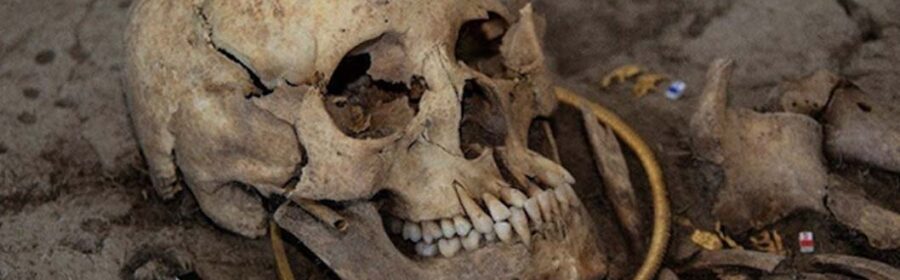

Archaeologists have discovered the earliest evidence of ancient man in Israel, a 1.5 million-year-old vertebra found at the prehistoric site of ‘Ubeidiya in the Jordan Valley. The international team of researchers say this adds growing ammunition to the theory that human dispersal out of Africa happened in successive waves, rather than a single event.

The research is published today in Scientific Reports.

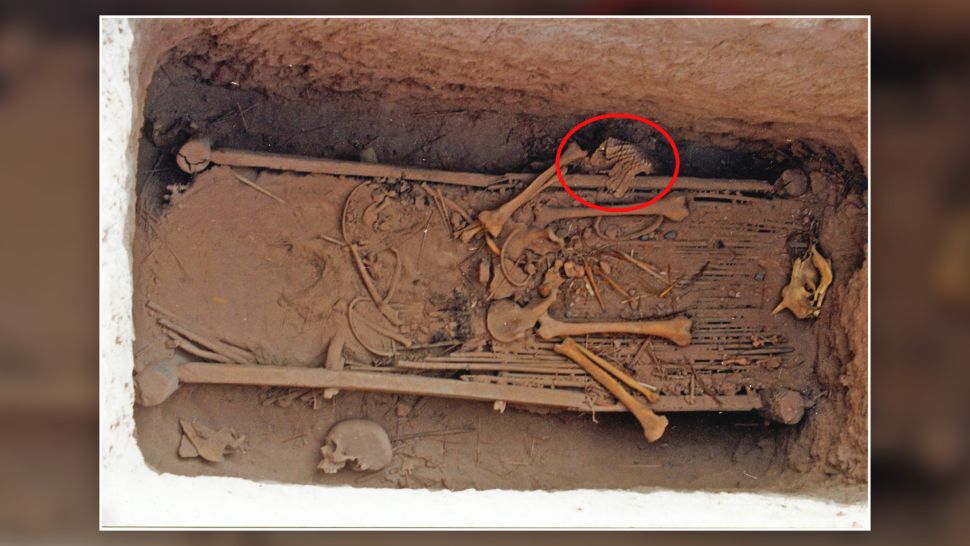

‘Ubeidiya is one of the oldest archaeological sites outside of Africa, with a rich record of finds including stone artefacts and the bones of extinct creatures such as sabre-toothed tigers and mammoths.

The site has been under investigation since the 1960s, but this latest work, funded by a grant from the US National Science Foundation, sought to use new dating methods to refine age estimates for these ancient human traces and to better understand the ecology and climate of the site as it was millions of years ago.

Who did the ‘Ubeidiya vertebra belong to?

The vertebra the team analysed likely belonged to a young male, 6-12 years old, who was particularly tall for his age.

“Had this child reached adulthood, he would have reached a height of over 180cm,” says Ella Been, a palaeoanthropologist at Ono Academic College, Israel, and an expert in spinal evolution.

Been says that makes the ‘Ubeidiya boy similar in size to other particularly tall ancient hominins found in East Africa, and this differs markedly from some of the other oldest human remains outside Africa, like the relatively diminutive people who lived at Dmanisi in Georgia some 1.8 million years ago.

What does this find tell us about our human story?

Human evolution research may seem to be an endless conveyor belt of new “oldest” and “earliest”, but that’s kind of the point: the more small pieces of the human puzzle we uncover, the more we learn about the epic story of our evolution and dispersal around the globe.

The prevailing scientific wisdom is that our ancestors evolved in Africa some six million years ago, and began to spread around the globe roughly two million years ago, according to the Out of Africa theory. But the routes are taken, the timing of the dispersal, and whether this dispersal was one singular event or a series of events, are all still up for debate.

“Due to the difference in size and shape of the vertebra from ‘Ubeidiya and those found in the Republic of Georgia, we now have unambiguous evidence of the presence of [at least] two distinct dispersal waves,” says study lead-author Alon Barash, of the Azrieli Faculty of Medicine at Bar-Ilan University, Israel.

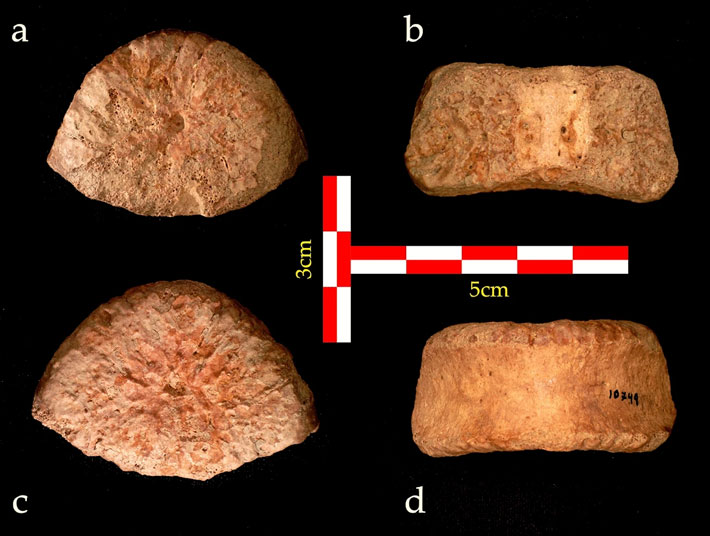

And the authors say that the humans who lived at Dmanisi and ‘Ubeidiya were technologically different, producing markedly different stone tools: the Dmanisi hominins were making Oldowan-style stone tools (some of the earliest stone-tool types found in Africa), while the ‘Ubeidiya hominins were making stone tools like those found in Acheulean assemblages, involving more complex types of tools.

The researchers think their discovery cements the evidence that successive waves of differently evolved hominins moved out of Africa at different times, and in response to different pressures.

“One of the main questions regarding the human dispersal from Africa were the ecological conditions that may have facilitated the dispersal,” explains Miriam Belmaker, study co-author from the University of Tulsa, US. “Previous theories debated whether early humans preferred an African savanna or new, more humid woodland habitat.

“Our new finding of different human species in Dmanisi and ‘Ubeidiya is consistent with our finding that climates also differed between the two sites,” Belmaker says. According to the study findings, ‘Ubeidiya is more humid and compatible with a Mediterranean climate, while Dmanisi is drier with savannah habitat.

This, according to Belmaker and team, is further evidence that we’re dealing with two different hominins.

“It seems, then, that in the period known as the Early Pleistocene, we can identify at least two species of early humans outside of Africa,” says Barash. “Each wave of migration was that of different kinds of humans – in appearance and form, technique and tradition of manufacturing stone tools, and ecological niche in which they lived.”