Dark secrets of Korea’s famous Wolseong palace complex are unearthed

Korea JoongAng Daily reports that a young woman’s remains have been unearthed at the site of Wolseong, a Silla Dynasty (57 B.C.–A.D. 935) palace complex in eastern South Korea.

Until 2017, the legend of Koreans’ practice of human sacrifice during large-scale construction to pray for the building to stand firm for a long time, remained a horrific myth. However, the archaeological discovery of human remains in Wolseong, a palace complex of the Silla Dynasty (57 B.C.-A.D. 935) located in Gyeongju, North Gyeongsang, turned this myth into fact.

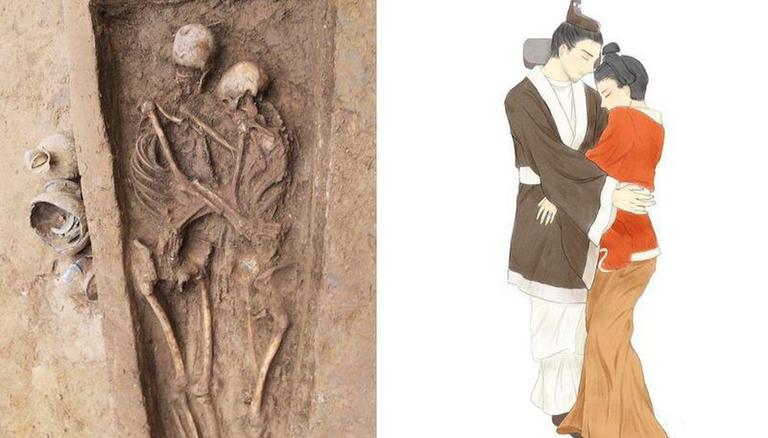

Remains from two people from the fifth century were discovered near the west entrance of Wolseong, throwing the nation into a state of shock. One was of a male and the other was a female. It was the country’s first archaeological evidence that proved that human sacrifice may have been a common practice for Silla people.

Remains of another female adult have been discovered, just 50 centimetres (1.64 feet) above the area where the couple was found in 2017, the Gyeongju National Institute of Cultural Heritage announced on Tuesday.

“Like the remains discovered in 2017, the recently discovered remains of a female adult showed no sign of struggle,” said Jang Ki-myeong, a researcher at Gyeongju National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage.

The woman, like the other two bodies, was laid to face the sky and is believed to have been in her 20s when she was sacrificed. The couple found in 2017 were in their 50s.

“The first thing we do when we find human remains is figuring out the gender and age,” said Kim Heon-Seok, another researcher from the institute. “Though her remains were also in good condition, her pelvis, which we use to find out the gender, was damaged, so we had to look at other things like her physique and height to figure it out.”

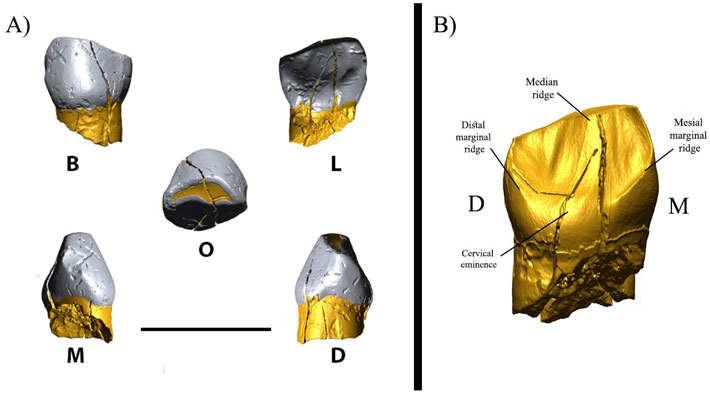

Like the two Silla people discovered in 2017, researchers believe the sacrificed humans are probably from lower-ranking class as they were “all quite undersized and had nutrition imbalances as seen from their teeth.”

Intact pottery was also discovered next to her head. Back in 2017, four pieces of pottery were found next to the feet of the sacrifices.

“When we did an x-ray of the pottery, we found a smaller bowl inside the jar. It looks like the larger pottery carried alcohol or some kind of liquid. It was buried together with the body,” said Jang. “This is not a common feature you witness in ancient tombs, but something similar was found at the 2017 site.”

When the remains of the two bodies were discovered, some raised the possibility that their deaths could have been accidental. But, the Cultural Heritage Administration concluded that the evidence — the remains showing no signs of struggle and the discoveries of animal bones and objects used for ancestral rites in the same area — clearly points that the pair died as part of a sacrificial ceremony.

“Now with the additional discovery, there’s no denying Silla’s practice of human sacrifice,” said Choi Byung-Heon, professor emeritus of archaeology at Soongsil University, adding that the specific location of where the remains were discovered is also important. According to Choi, the remains of three Silla people were laid on top of the bottommost layer of the fortress’s west wall, right in front of where the west gate would have been located.

“After finishing off the foundation and moving onto the next step of building the fortress, I guess it was necessary to really harden the ground for the fortress to stand strong. In that process, I think the Silla people held sacrificial rites, giving not only animals but also humans as sacrifices,” said Choi.

Geology Professor Lee Seong-Joo of Kyungpook National University also said there are records of human sacrifices in neighbouring China, by people of the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 B.C.) when constructing large buildings and these sacrifices were commonly found near entrances.

“Historical records say such rituals were carried out before making the gates or just before engaging in the most important part of the construction process,” Lee said.

“Samguksagi,” or “The Chronicles of the Three States” states that Wolseong was built in year 101 and was used for 800 years as the residence of Silla kings until Silla gave way to the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392). But by studying the pieces of pottery unearthed from the fortress, researchers predicted the date of its construction to be somewhere between the fourth and fifth centuries.

There’s been a clear gap between the two, and debates among researchers. The Gyeongju National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage said it has managed to settle the debate by scientifically proving that the construction period began in the early fourth century and it took about 50 years to complete.

“By analyzing the data collected through a newly adopted technology known as AMS [Accelerator Mass Spectrometer] and cross-checking with the existing data we have, we were able to provide a more reliable construction period,” said Jang from the institute.

Does that mean there are factual errors in Korea’s historical documents?

Jang says it’s better to approach the issue as, “Why is it recorded as 101?”

“We should further the research on Wolseong and try to find out what may have resulted in making such a record,” Jang added. “Wolseong is a vast research area not only in terms of its literal size but also academically and historically.”

The official excavation research of Wolseong began in December 2014.

Literally translated as “moon castle” in English, Wolseong, which is also listed at Unesco World Heritage, measures more than 200,000 square meters and is considered one of the most important historical sites in Korea as it was the seat of the Silla Dynasty. Compared to its historical weight, the Wolseong area had been left largely unexplored.

The government previously conducted several different inspections and excavations, which resulted in the discovery of the remains of 20 Silla people, just 10 meters away from the site where the recent remains were discovered, during two separate inspections in 1985 and 1990. Researchers at the Gyeongju National Institute of Cultural Heritage believe the discoveries are of great significance but have yet to conclude if the remains were part of sacrificial rites.

“As for the remains of the 20 people, only three people’s remains were in good condition while the rest were just scattered across a vast area with animal bones,” said Jang. “It is certain that they are related to Wolseong but we need to conduct more research to find out if they were human sacrifices.”

Researchers believe they may discover more human remains in Wolseong, but more importantly, “so much more about the unknown 1,000 years of Silla,” said Jang.

“We’ve discovered the method of building Wolseong, which mainly used soil,” said Ahn So-Yeon, a researcher from the institute. “We’ve discovered how Silla people mixed stones, pieces of wood, seeds of fruits and grains with soil to make the fortress stronger.”

Professor Lee from Kyungpook National University said Silla had built the strongest and highest fortress compared to Goguryeo and Baekje.

“The fundamental power of unification can also be found in the fortress. A more specific time period and the revealed methodology are significant to the researchers of this field,” Lee said.