Oldest Known Spearthrowers Found At 31,000-Year-Old Archaeological Site Of Maisières-Canal

The hunter-gatherers who settled on the banks of the Haine, a river in southern Belgium, 31,000 years ago were already using spearthrowers to hunt their game. This is the finding of a new study conducted at TraceoLab at the University of Liège.

The material found at the archaeological site of Maisières-Canal permits establishing the use of this hunting technique 10,000 years earlier than the oldest currently known preserved spearthrowers.

This discovery, published in the journal Scientific Reports, is prompting archaeologists to reconsider the age of this important technological innovation.

The spearthrower is a weapon designed for throwing darts, which are large projectiles resembling arrows that generally measure over two meters long. Spearthrowers can propel darts over a distance of up to 80 meters.

The invention of long-range hunting weapons has had significant consequences for human evolution, as it changed hunting practices and the dynamics between humans and their prey, as well as the diet and social organization of prehistoric hunter-gatherer groups.

The date of invention and spread of these weapons has therefore long been the subject of lively debate within the scientific community.

“Until now, the early weapons have been infamously hard to detect at archaeological sites because they were made of organic components that preserve rarely,” explains Justin Coppe, researcher at TraceoLab.

“Stone points that armed ancient projectiles and that are much more frequently encountered at archaeological excavations have been difficult to connect to particular weapons reliably.”

Most recently published claims for early use of spearthrowers and bows in Europe and Africa have relied exclusively on projectile point size to link them to these weapon systems.

However, ethnographic reviews and experimental testing have cast serious doubt on this line of reasoning by showing that arrow, dart, and spear tips can be highly variable in size, with overlapping ranges.

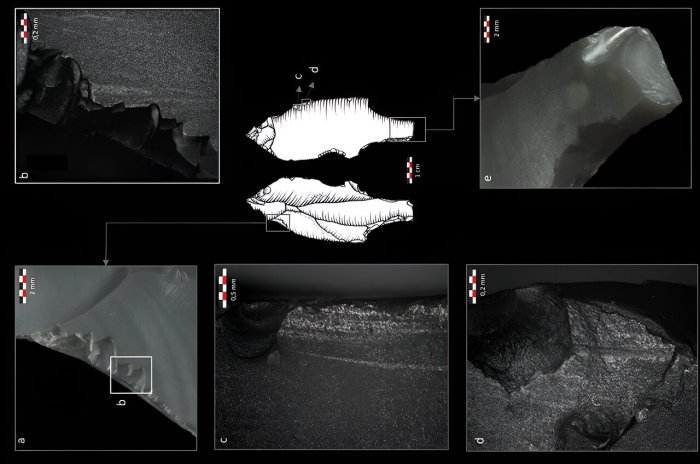

The innovative approach developed by the archaeologists at TraceoLab combines ballistic analysis and fracture mechanics to gain a better understanding of the traces preserved on the flint points.

“We carried out a large-scale experiment in which we fired replicas of paleolithic projectiles using different weapons such as spears, bows and spearthrowers,” explains Noora Taipale, FNRS research fellow at TraceoLab.

“By carefully examining the fractures on these stone points, we were able to understand how each weapon affected the fracturing of the points when they impacted the target.”

Each weapon left distinct marks on the stone points, enabling archaeologists to match these marks to archaeological finds. In a way, it’s like identifying a gun from the marks the barrel leaves on a bullet, a practice known in forensic science.

The excellent match between the experimental spearthrower sample and the Maisières-Canal projectiles confirmed that the hunters occupying the site used these weapons.

This finding encourages archaeologists to apply the method further to find out how ancient long-range weaponry really is. Future work at TraceoLab will focus on adjusting the analytical approach to other archaeological contexts to help reach this goal.