Cosmic-Ray Muons Reveal Hidden Void in the Great Pyramid

Cosmic rays have revealed a hidden void inside the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt, scientists said Thursday. They don’t know what’s in it or what it was built for, but it does not look like a secret burial chamber.

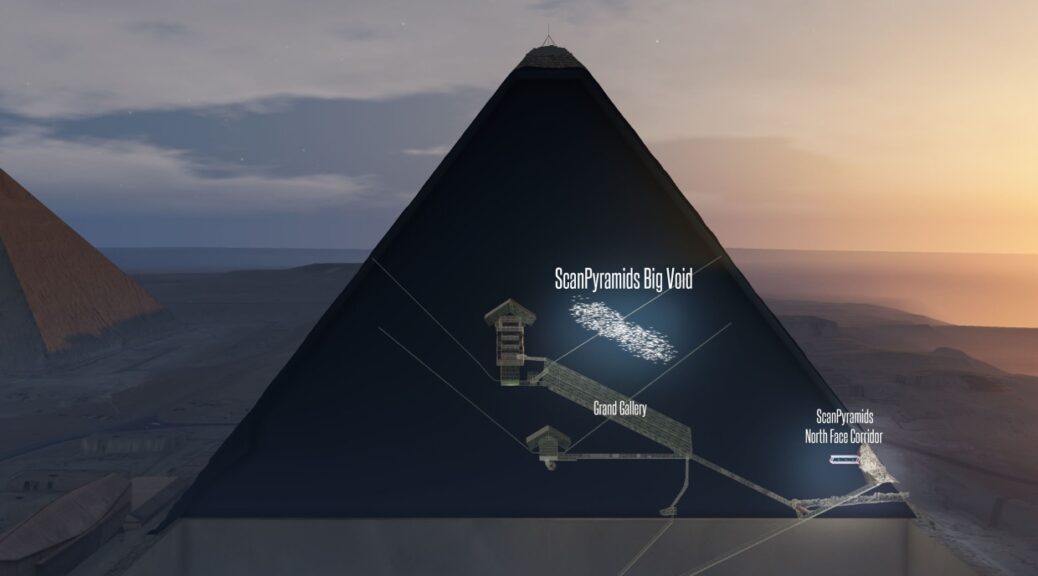

It’s shaped more like a 30-yard-long gallery or corridor, the international team of researchers reported in the journal Nature.

“We open the question to Egyptologists, architects and archaeologists: what could it be?” Hany Helal of Cairo University told reporters on a telephone briefing.

“We don’t know for the moment if it’s horizontal or inclined if it is made from one structure or several successive structures,” Mehdi Tayoubi, president of France’s Heritage Innovation Presentation (HIP) Institute, added.

“What we do know is that this void is there, that it is impressive, that it was not expected by any kind of theory.”

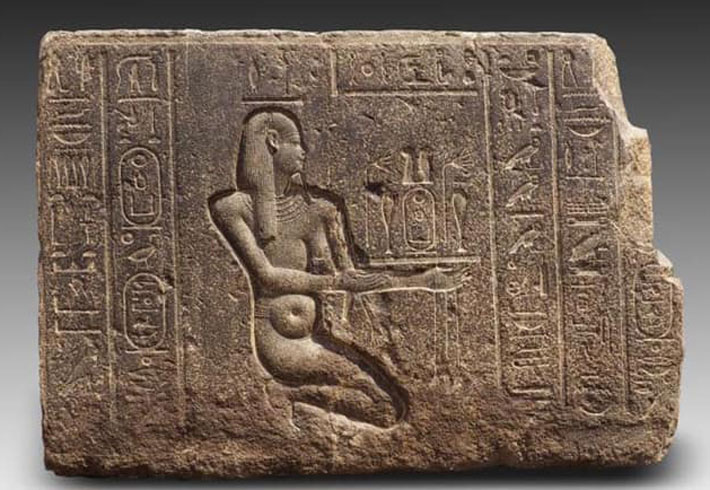

Rumours have abounded for centuries about hidden rooms in the pyramids at Giza. But it’s hard to get through the tons of stone blocks used to make the 455-foot-high great pyramid of Khufu (or Cheops.) Radar can’t do it well.

“A lot of people tried to dig some tunnels looking for chambers,” Tayoubi said. Tourists get in through the “robbers’ tunnel,” dug out centuries ago.

Visitors looking for mummies or treasure have been disappointed. The 4,500-year-old tomb was robbed millennia ago.

Yet archaeologists have long believed there is more to the inside than the three chambers, corridors and air shafts that have been discovered.

The international ScanPyramids team used special film plates to catch, over a period of months, particles called muons that are created when high-energy cosmic rays hit the upper atmosphere.

They are few and far between — that’s why it took months — but they can pass through the stone and collect on the plates.

They produced a fuzzy image of some kind of open space above what’s known as the Grand Gallery of the pyramid.

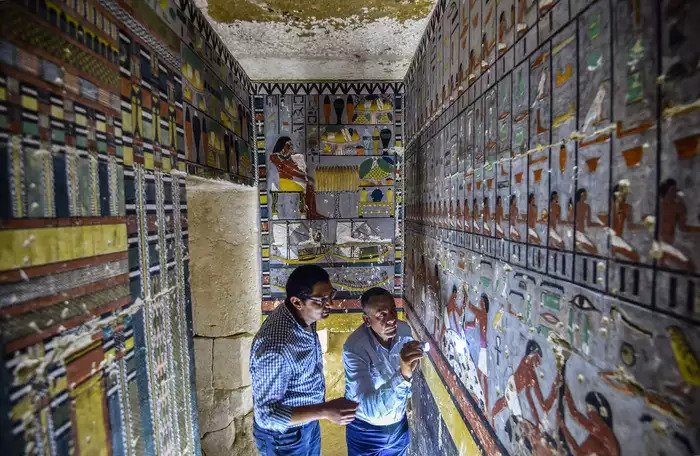

“These results constitute a breakthrough for the understanding of Khufu’s Pyramid and its internal structure,” the researchers wrote. “While there is currently no information about the role of this void, these findings show how modern particle physics can shed new light on the world’s archaeological heritage.”

It’s the “first major inner structure found in the Great Pyramid since the 19th century,” the team added.

Muon imaging has also been used to peer inside Fukushima’s nuclear reactor, at archaeological sites near Rome and into the Teotihuacan Pyramid of the Sun in Mexico.

Now the question is how to get a better look at what’s in there, but that would require drilling.

Nonetheless, Jean-Baptiste Mouret of France’s national institute for computer science and applied mathematics is working to design a small drone that could explore the space if the team gets permission from the Egyptian government.

Last year, the same team used muon detection and infrared measurements to image some kind of corridor right above the entrance to the pyramid.