Archaeologists Found 12th Century Medieval Castle in England

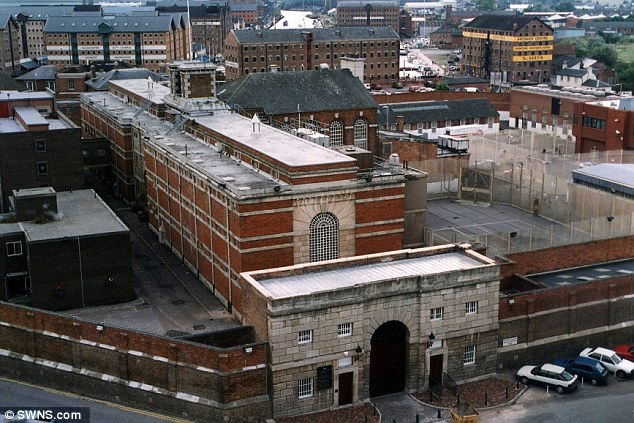

The greatest archeological and historical discoveries are often found in the most unlikely of places. This was the case in December, when construction laborers were left in awe while renovating a men’s prison in Gloucester, England.

Back around the year 1110, the rulers of Gloucester built an impressive castle ”similar to the Tower of London,” It had 3 chapels, 2 drawbridges, and walls that were a solid 12 feet wide.

During the 15th century reign of Richard III (the hunchback ruler with a bad reputation who was recently found buried under a parking lot), the castle became a country jail.

For the next 200 years or so, it served as a makeshift lockup until, in 1787, it was knocked down to make way for a dedicated Jail. This prison, which closed in 2013 after many updates to the buildings, is now in the process of being renovated.

When the old basketball court was dug up, an archaeological group found a wall from the original castle just two feet beneath the ground. It’s not clear yet what this discovery means for the future of the site.

It was slated for redevelopment of some sort, but as one local planner told the Gloucester Citizen, “you can not just ignore that there is a castle there.”

Intending to tear down and replace the old facility, the team was forced to halt the project when they unearthed pieces of near ancient history. So just what, exactly, was down there? Would you believe it was a medieval castle?

They believe the castle was built between 1110 and 1120, and “was a large structure, with the keep, which we have now located in our work, an inner bailey and stable.

The keep was surrounded by a series of concentric defences which comprised curtain walls and ditches, with the drawbridge and gatehouse lying outside the current site toward the north.”

The keep is believed to have been 30 metres in length and 20 metres wide, and had walls as thick as 12 feet. Neil Holbrook, chief executive of Cotswold Archaeology, told the Western Press Daily, “I am surprised by what we Discovered.

I knew there was a castle however I had expected more of it to have been destroyed.” He added the size and design would have been similar to the Tower of London.

“It would have been a powerful symbol of Norman architecture engineering,” he said. “As you came to Gloucester you would have seen the cathedral and the castle, which is representative of how important the city was in Norman Britain.”

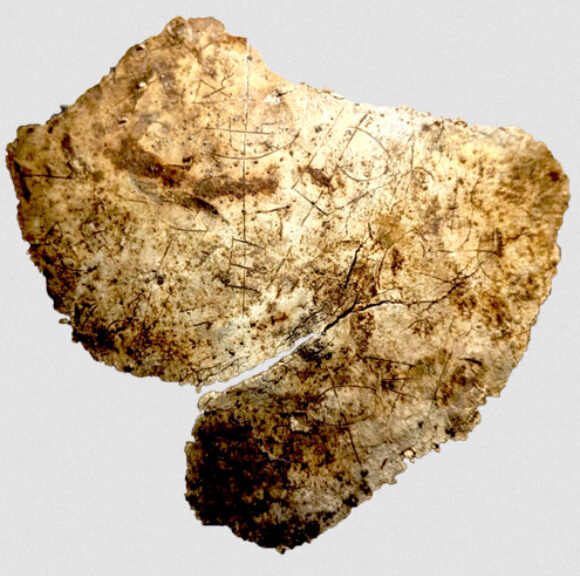

The archaeologists have so far discovered nearly 900 objects, including medieval pottery and a 6-sided die made of bone. It was believed that the castle had been destroyed in the eighteenth century when a prison was built on the site, however, it seems that the gaol was built over the medieval structure.

The jail was in use until 2013 and is set for redevelopment. News of the discovery is leading to calls that the site is protected. Paul James, Leader of Gloucester City Council explained to the Gloucester Citizen, “Whatever is done on-site needs to be sensitive to the heritage of both the castle and the listed buildings there.

We are blessed that we have a designer that cares about the heritage of the site. Having glass flooring above it, allowing visitors to see through might be a possibility. The most important matter is to preserve it well, the walls have been here for many years and we want them here for hundreds more.”