Bronze Age logboat remains found at Faversham boatyard

In a Cambridgeshire quarry in the suburbs of Peterborough, a group of eight ancient vessels, including a float about nine meters long. The boats, all purposely sunk more than 3,000 years ago, are the largest group of vessels in the Bronze Age in the same UK, most of whom are remarkably well preserved.

One is covered inside and out with decorative carving described by conservator Ian Panter as looking “as if they’d been playing noughts and crosses all over it”.

Another has handles carved from the oak tree trunk for lifting it out of the water. One still floated after 3,000 years and one has traces of fires lit on the wide flat deck on which the catch was evidently cooked.

Many had ancient repairs, including clay patches and an additional section shaped and pinned in where a branch was cut away. They were preserved by the waterlogged silt in the bed of a long-dried-up creek, a tributary of the River Nene, which buried them deep below the ground.

“There was huge excitement over the first boat, and then they were phoning the office saying they’d found another, and another, and another, until finally, we were thinking, ‘Come on now, you’re just being greedy,'” Panter said.

The boats were deliberately sunk into the creek, as several still had slots for transoms – boards closing the stern of the boat – which had been removed.

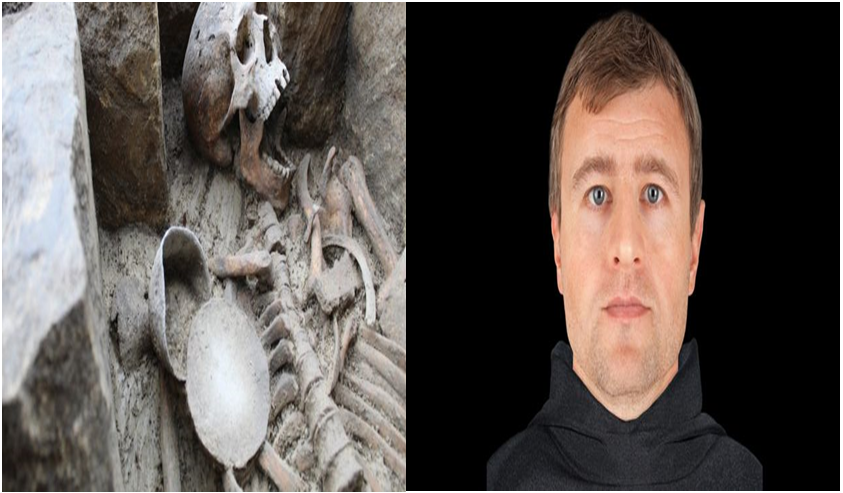

Archaeologists are struggling to understand the significance of the find. Whatever the custom meant to the bronze age fishermen and hunters who lived in the nearby settlement, it continued for centuries. The team from the Cambridge Archaeological Unit is still waiting for the results of carbon 14 dating tests but believes the oldest boats date from around 1,600 BC and the most recent 600 years later.

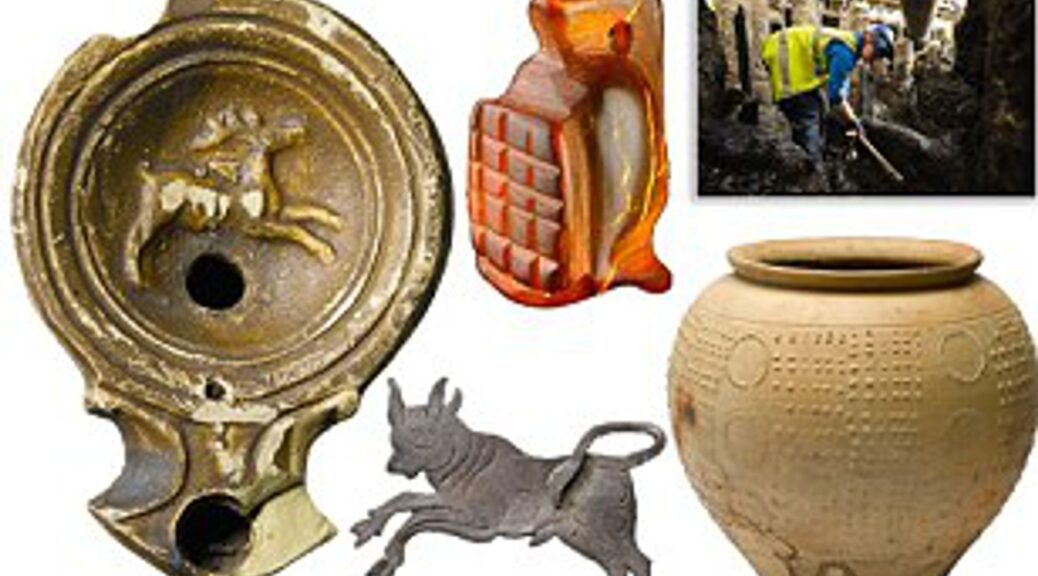

They already knew the creek had great significance – probably as a rich source of fish and eels – as in previous seasons at the Much Farm site they had found ritual deposits of metalwork, including spears.

The boats themselves may have been ritual offerings or may have been sunk for more pragmatic reasons, to keep the timber waterlogged and prevent it from drying out and splitting when not in use – but in that case it seems strange that such precious objects were never retrieved.

Some of the boats were made from huge timbers, including one from an oak which must have had a meter-thick trunk and stood up to 20 meters tall. This would have been a rare specimen as sea levels rose and the terrain became more waterlogged, creating the Fenland landscape of marshes, creeks, and islands of gravel.

“Either this was the Bermuda Triangle for bronze age boats, or there is something going on here that we don’t yet understand,” Panter said.

Kerry Murrell, the site director, said: “Some show signs of long use and repair – but others are in such good condition they look as if you could just drop the transom board back in and paddle away.”

The boats were all nicknamed by the team, including Debbie – made of lime wood, and therefore deemed a blonde – and French Albert the Fifth Musketeer, the fifth boat found. Murrell’s favourite is Vivienne, a superb piece of craftsmanship where the solid oak was planed down with bronze tools to the thickness of a finger, still so light and buoyant that when their trench filled with rainwater, they floated it into its cradle for lifting and transportation.

Because the boats were in such striking condition, they have been lifted intact and transported two miles, in cradles of scaffolding poles and planks, for conservation work at the Flag Fen archaeology site – where a famous timber causeway contemporary with the boats was built up over centuries until it stretched for almost a mile across the fens.

“My first thought was to deal with them in the usual way, by chopping them into more manageably sized chunks, but when I actually saw them they just looked so nice, I thought we had to find another way,” Panter, an expert on waterlogged timber from York Archaeological Trust, said. “I think if I’d arrived on the site with a chainsaw, the team would have strung me up.”

Must Farm, now a quarry owned by Hanson UK, which has funded the excavation, has already yielded a wealth of evidence of prehistoric life, including a settlement built on a platform partly supported by stilts in the water, where artifacts including fabrics woven from wool, flax, and nettles were found. Instead of living as dry-land hunters and farmers, the people had become experts at fishing: one eel trap found near the boats is identical to those still used by Peter Carter, the last traditional eel fisherman in the region.

The boats will be on display at Flag Fen, viewed through windows in a container chilled to below 5c – funded with a £100,000 grant from English Heritage which regards their discovery as of outstanding importance – built within a barn at the site. At the moment conservation technician Emma Turvey, dressed in layers of winter clothes, is spending up to eight hours a day spraying the timbers to keep them waterlogged and remove any potentially decaying impurities. They will then be impregnated with a synthetic wax, polyethylene glycol, before being gradually dried out over the next two years for permanent display.

Murrell is convinced there is more to be found down in the silt.

“The creek continued outside the boundaries of the quarry, so it’s off our site – but the next person who gets a chance to investigate will find more boats, I can almost guarantee it.”