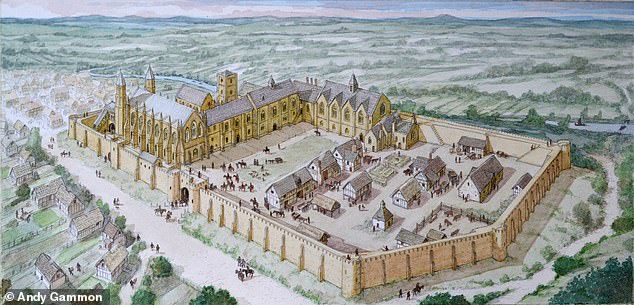

A stunning 14th-century medieval chapel is uncovered in County Durham, England

Archaeologists have really found considered one of medieval Britain’s most vital architectural works of arts– the long-lost church of north England’s only medieval leaders– the Prince-Bishops of Durham.

The precise space of the large 40- meter lengthy baronial church was unidentified for tons of years. Now archaeologists from Durham College in addition to a neighborhood historic activity have really found the church’s long-lost stays.

A lot, they’ve really found ultra-fine stonework from the church wall surfaces, a fragile rock rising from the ceiling, items of rock columns, beautiful discolored glass in addition to the church’s distinct black plaster flooring.

The locates have really allowed them to recreate an image of what the fantastic church will surely have resembled within the later middle ages The archaeologists have really likewise uncovered part of the enamel in addition to copper sacred dish utilized to carry the communion bread all through options held there by the Prince-Bishops within the 14th century.

They’ve really likewise found an image of a stooping monk– regarded as north-east England’s hottest medieval non-secular chief, St Cuthbert (whose vital temple continues to be in Durham Cathedral). It is without doubt one of the extraordinarily couple of medieval photographs of him ever earlier than found.

Larger than the Royal Chapel at Westminster (St Stephen’s in parliament) in addition to virtually as massive as St George’s Chapel, Windsor, it was developed by the Bishop in addition to Earl Palatine of Durham as part of his main out-of- group baronial citadel within the late 13th century.

So efficient was its contractor, Prince-Bishop Bek, that considered one of his distinguished authorities flaunted that there have been 2 majesties in England– the King in addition to the prince-bishop.

However in the end, three in addition to a fifty % centuries in a while, the fantastic baronial church, at Auckland Fortress, County Durham, was deliberately ruined with massive quantities of gunpowder by yet another megalomaniac– a callous anti-royalist that hungered for outright energy, detested the well-known church in addition to despised all diocesans.

The ultra-intolerant extremist was Sir Arthur Hesilrige, an aged legislator military chief that was one of many arch-republicans that, in 1649, approved King Charles I’s fatality warrant.

The church in addition to the citadel it developed part of had really remained in pro-royalist arms– in addition to had really been confiscated by parliament in addition to marketed to Hesilrige, the simplest republican politician in north-east England, known as, of a scriptural dangerous man, the “Nimrod of the North” by his challengers.

As an extreme Puritan, he despised the Church of England– in addition to maltreated its clergy, on one celebration kicking out a vicar in addition to his family from their home within the middle of the night, tossing their private belongings proper into the neighborhood graveyard.

Certainly, considered one of Civil Struggle England’s main left-wing democrats, John Lilburne, chief of the ultra-egalitarian Levellers, charged him of“traitorously subverting the elemental liberties of England and exercising an arbitrary and tyrannical authority over and above the regulation”

Hesilrige’s conduct– together with his procurement in addition to the purposeful injury of the church– is politically vital in English background since, along with comparable habits by varied different main Cromwellians, it aided fatally problem the rationale of republicanism in addition to therefore aided in its failure in addition to the restore of the monarchy.

Stained glass from the long-lost baronial church. This piece reveals a pelican pecking her very personal bust– a typical Christian signal standing for Christ’s self-sacrifice. (Durham College utilized with authorization of the Auckland Venture). The exploration of the church is of appreciable worth by way of the background of north England

“For hundreds of years it has been one of many nice misplaced buildings of medieval England,” said one of many essential archaeologists related to the excavation, John Castling, archaeology in addition to social background supervisor on the Auckland Venture, which has the citadel.

“Our excavation of this big chapel has shed extra mild on the immense energy and wealth of the Prince-Bishops of Durham – and has helped bolster Auckland Fortress’s fame as a fortress of nice significance within the historical past of England.”

A number of the brand-new explorations will definitely be positioned on present and inform at Auckland Fortress from the very early the following month.

The church was uncovered making use of superior distant noticing gadgets– consisting of ground-penetrating radar in addition to magnetometers– in addition to was moneyed by way of the custom of the late Mick Aston, the favored TELEVISION excavator in addition to the speaker of the Channel four historic assortment, TimeTeam

Referring to the excavation of the church, Durham College excavator, Chris Gerrard said: “That is archaeology at its best.”

“Professionals, volunteers, and Durham College students working collectively as a staff, to piece collectively clues from paperwork and previous illustrations, used the very newest survey methods to resolve the thriller of the whereabouts of this big misplaced construction,” he included.