Secret doorway in Parliament leads to a historical treasure trove

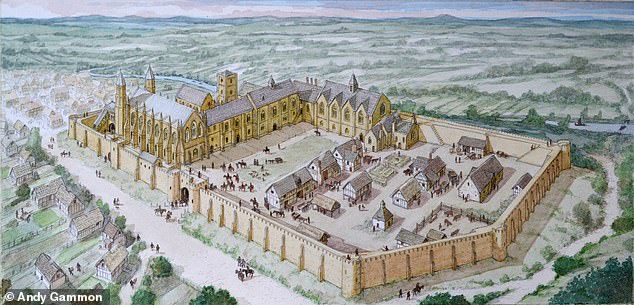

Renovation workers have uncovered a forgotten passageway in the UK’s Houses of Parliament. Built over 1,000 years ago, the historic seat of government in central London has seen kings and queens, prime ministers and foreign dignitaries come and go time and again over the centuries.

While it might seem as though all of the building’s secrets would have been found by now, this week there was a surprise in store when renovation workers uncovered a secret door leading to a hidden passageway that dates back over 360 years.

Believed to have been originally built for the coronation of Charles II in 1660, the passageway would have enabled guests to attend a celebratory banquet in the neighboring Westminster Hall. It went on to be used by countless MPs before eventually being blocked up and concealed. It was even rediscovered briefly in the 1950s before being sealed up again.

“To say we were surprised is an understatement – we really thought it had been walled-up forever after the war,” said Mark Collins, Parliament’s Estates Historian.

Liz Hallam Smith, the historical consultant to Parliament’s architecture and heritage team, said: “I was awestruck because it shows that the Palace of Westminster still has so many secrets to give up. “It is the way that the Speaker’s procession would have come, on its way to the House of Commons, as well as many MPs over the centuries, so it’s a hugely historic space.”

The current occupant of the Speaker’s chair, Sir Lindsay Hoyle, said: “To think that this walkway has been used by so many important people over the centuries is incredible. I am so proud of our staff for making this discovery.”

A brass plaque, erected in Westminster Hall in 1895, marks the spot where the doorway once was but, says Dr. Hallam Smith, “almost nothing was known about it”. It lay behind thick masonry, on the hall side, and wooden panelling, running the full length of a Tudor cloister, on the other side.

Up until three years ago, the cloister had been used as offices by the Labour Party, and before that, a cloakroom for MPs. It was Dr. Hallam Smith who discovered evidence of a small, secret access door that had been set into the cloister’s panelling, during Parliament’s last major renovation in 1950.

“We were trawling through 10,000 uncatalogued documents relating to the palace at the Historic England Archives in Swindon when we found plans for the doorway in the cloister behind Westminster Hall.

“As we looked at the panelling closely, we realized there was a tiny brass key-hole that no-one had really noticed before, believing it might just be an electricity cupboard.” The team turned to Parliament’s locksmith for help and, with some difficulty, he was able to open the wood panel door, to reveal a tiny, stone-floored chamber, with a bricked-up doorway on the far wall.

They discovered the original hinges for two wooden doors 3.5m high, that would have opened into Westminster Hall. They also found graffiti dating back to the rebuilding of Parliament, in a neo-Gothic style, following the fire in 1834 which destroyed much of the medieval palace.

The scrawled pencil marks, left by men who helped block the passageway on both sides in 1851, read: “This room was enclosed by Tom Porter who was very fond of Ould Ale.” It then names the witnesses of “the articles of the wall” – evidently architect Sir Charles Barry’s masons who had joined bricklayer’s labourer Thomas Porter in a toast to mark the room’s enclosure. The men can be traced in the 1851 census returns as Richard Condon, James Williams, Henry Terry, Thomas Parker, and Peter Dewal.

Finally, the graffiti notes: “These masons were employed refacing these groines…[ie repairing the cloister] August 11th, 1851 Real Democrats.”

This reference to “real democrats” suggests the group were part of the Chartist movement, which campaigned for every man aged 21 to have a vote, and for would-be MPs to be allowed to stand even if they did not own property.

“Charles Barry’s masons were quite subversive,” said Dr. Hallam Smith.

“They had been involved in quite a few scraps as the Palace was being built. I think these ones were being a little bit bolshie but also highly celebratory because they had just finished the first major restoration of these beautiful Tudor cloisters.”

The team are keen to trace the descendants of Tom Porter and his colleagues and have already discovered that the workers lived in lodgings near Parliament. There was another surprise for the team when they entered the passageway – they were able to light the room.

A light switch – probably installed in the 1950s – illuminated a large Osram bulb marked ‘HM Government Property’. The team is eager to learn more about the history of this hardy bulb. Dr. Collins said further investigations made him certain the doorway dated back at least 360 years.

Dendrochronology testing revealed that the ceiling timbers above the little room dated from trees felled in 1659 – which tied in with surviving accounts that stated the doorway was made in 1660-61 for the coronation banquet of Charles II.

This is in contrast to the words on the brass plaque in Westminster Hall, which state the passageway was used in 1642 by Charles I when he attempted to arrest five MPs, which the researchers believe is not accurate. Dr. Collins said the plans that led to their discovery will now be digitized as part of the Parliament’s Restoration and Renewal program.

“The mystery of the secret doorway is one we have enjoyed discovering – but the palace no doubt still has many more secrets to give up,” he added.

“We hope to share the story with visitors to the palace when the building is finally restored to its former glory, so it can be passed on down the generations and is never forgotten again.”