Researchers stumbled upon a box of human bones that had been missing for 100 years

The long-lost bones of a Viking nobleman have been found in the archives of the Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, more than 50 years after the remains were mislabeled and vanished into museum storage.

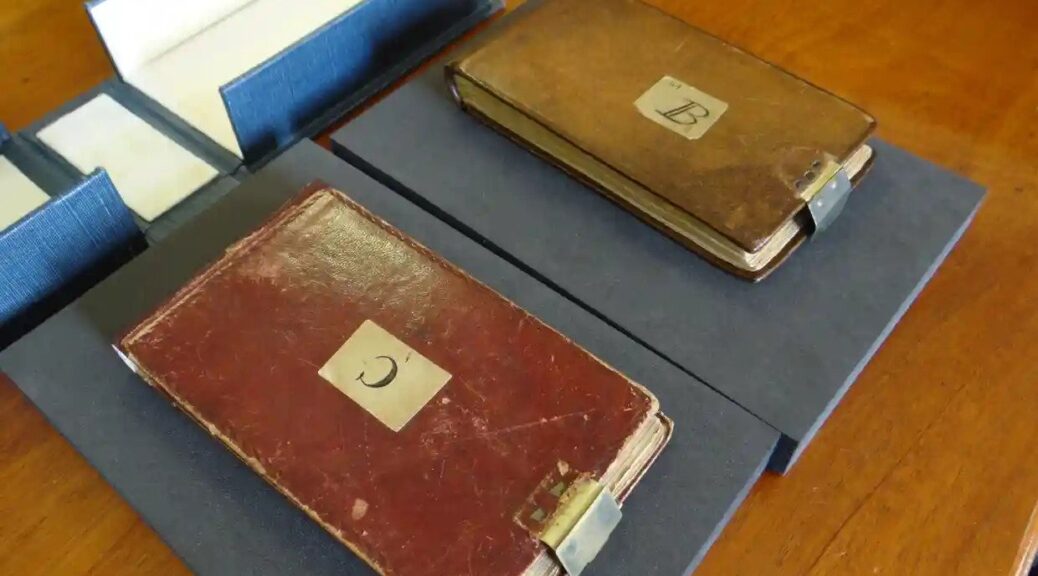

These artefacts came from the burial of a wealthy Viking man in Bjerringhøj, Denmark, dating to around A.D. 970, and they were excavated in 1868. Researchers brought the artefacts and remain to the Museum of Denmark for analysis, but the bones were misplaced sometime during the 20th century.

Archaeologists recently found the missing bones among artefacts and remain from another Danish Viking Age burial site, in Slotsbjergby; the mixup between the two graves likely happened “between the 1950s and 1984,” according to a new study. New analyses of the bones and fabric confirmed that the remains belonged to an older man who was likely rich and important, as he was buried in a very fancy pair of trousers, the study authors reported.

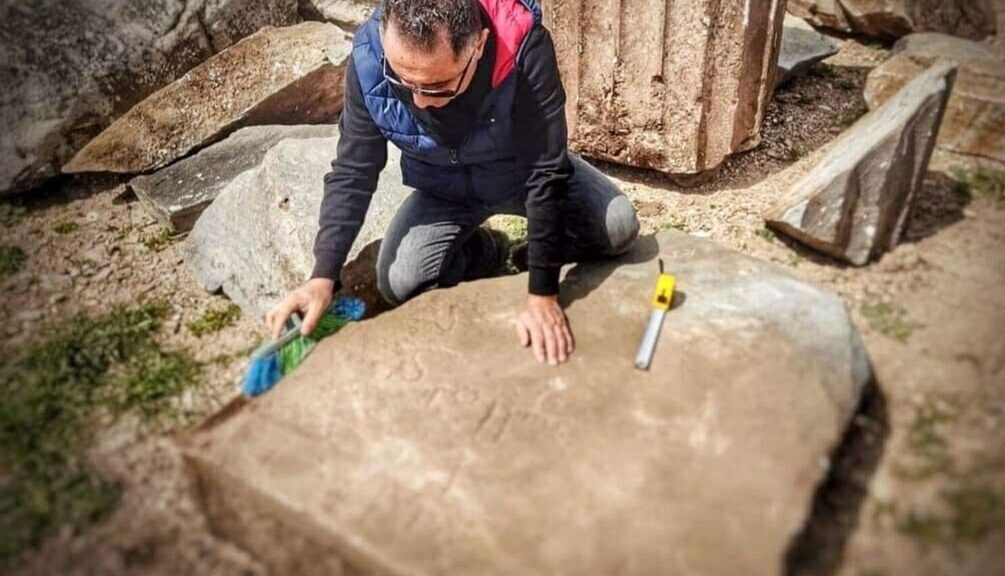

It wasn’t archaeologists who initially discovered the Bjerringhøj burial. Farmers in the village of Mammen unearthed the mound, finding a clay-sealed wooden chamber with a coffin inside; they then opened the chamber and generously “shared” its contents among their friends. Arthur Feddersen, a local schoolmaster with an interest in archaeology, heard about the find and travelled to Mammen, but by the time Feddersen got there, he found only “fragments of textiles, clumps of down feathers and human bones scattered in the soil” at the burial site, according to the study.

“The grave was more or less looted,” said study co-author Ulla Mannering, a research professor of ancient cultures of Denmark and the Mediterranean at the National Museum of Denmark.

Feddersen promptly visited the farmers’ homes to collect and catalogue all the objects; the mound was eventually identified as a high-status Viking burial. The man in the coffin wore garments that were decorated with silk and stitched with gold and silver thread, and he was placed on a layer of down feathers that may have been stuffed inside a mattress. He was also buried with two iron axes, one of which had silver inlay, and there was a beeswax candle attached to his coffin lid.

But after the bones were brought to the museum, their trail — somehow — went cold. During the late 19th century, human remains weren’t considered to be archaeological artefacts, and one possible explanation is that the bones were separated from the rest of the Bjerringhøj objects in the decades after they were discovered, Mannering told Live Science.

“It’s very likely that the bones were put aside, maybe awaiting some decision about how they were going to be recorded at the museum,” and they were never returned to their proper place, Mannering said.

Subsequent efforts to locate the bones met with failure; the remains weren’t found in 1986, during a search of the museum’s collection, nor did they turn up in 2009, in a search of the Anthropological Collection at the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Forensic Medicine, “where most of the human remains belonging to the National Museum of Denmark’s prehistoric collections are stored,” the study authors reported.

“It seemed that the bones had been lost forever,” the researchers wrote.

Who wears the pants?

Mannering first glimpsed the wayward remains in 2017 — though she didn’t know it at the time — while reviewing artefacts from another Viking burial site called Slotsbjergby, she told Live Science. Details in the textiles from one box differed dramatically from fabrics in the rest of the Slotsbjergby crates, “but my main focus was not the bones,” and so she didn’t investigate the box’s contents further, Mannering said.

However, when Mannering later embarked on a new project about fashion in the Viking Age, she remembered those textiles and revisited the alleged Slotsbjergby box. Pieces of the fabric in that box were wrapped around the ankle of the person’s leg bones, so the scientists determined that it was part of a cuff for a pair of long trousers. As the individual in the Slotsbjergby burial was a woman and trousers were only worn by Viking men, this strongly suggested that the bones came from a different burial.

The technique that shaped the pants cuff was also highly unusual. Small strips of fabric had been rolled and joined together, and the cuff was further decorated by a band that was woven on a tablet.

“This is a detail that hasn’t been seen before to my knowledge in any Viking Age find in Denmark,” Mannering said.

However, the structure of this peculiar rolled-fabric trouser cuff closely resembled that in a pair of well-preserved sleeve cuffs from the Bjerringhøj burial, whose occupant was male. The scientists verified their hypothesis by comparing the fabric and remains with objects from Bjerringhøj, using computed X-ray tomography (CT) scans and radiocarbon dating to examine the bones; they also analyzed fibres and dyes in the textiles.

“There can be no doubt that these bones are from the Bjerringhøj grave,” Mannering said.

Their analysis showed that the Bjerringhøj man was an adult, around 30 years old or possibly older when he died, and signs of inflammation around his knees may reflect an active lifestyle that included lots of horseback riding, study authors reported. Judging by the elaborateness of his fancy pants, this Viking noble may also have been a bit of a clothes horse.

“The design of the trousers is really exquisite, with silk, and silver and gold threads,” Mannering said. “There are lots of colours and very unusual details attached to his costume — he must have looked really fantastic.”

The findings were published online in the journal Antiquity.