Magnificent 2 Meters Tall Marble Apollo Statue And Other Artifacts Found In San Casciano dei Bagni, Italy

Archaeologists excavating at Bagno Grande in San Casciano dei Bagni, Italy, have all reasons to celebrate. The 2023 excavation campaign that lasted three months resulted in many new and exceptional discoveries.

Located 110 km southeast of Florence and 70 km southeast of Siena, Bagno Grande, San Casciano dei Bagni, Tuscany is of great historical and archaeological importance.

Famous for its numerous springs of sulfurous waters spread throughout its territory, the San Casciano dei Bagni village has long attracted visitors from all over Europe.

As previously reported on Ancient Pages, archaeologists have been excavating at the site for a long time, and their work has been rewarding. Among the many finds, one can mention an extraordinary Etruscan and Roman treasure trove unearthed last year. Equally interesting are two dozen amazingly well-preserved bronze statues discovered in the thermal baths of San Casciano dei Bagni.

Thanks to the mud that protected them, the two dozen figurines and other bronze objects were found in perfect conservation, bearing delicate facial features, inscriptions, and rippled tunics. Alongside the figures were 5,000 coins in gold, silver, and bronze.

These are only a few fabulous archaeological finds at the site. The Italian archaeology team has now encountered an Etruscan structure beneath the temple with the large sacred Roman.

The thermal water that flows in the heart of the temple, with over 25 liters of hot water per second, is increasingly confirmed as the ritual and cultic engine of the sanctuary. Scientists are now also occupied with documenting the ancient inscriptions on the bronze statues.

The information will explain how the Etruscans and Romans used the temple and sacred basin. One of the most intriguing unearthed inscriptions is bilingual Etruscan-Latin.

It is a rare example of bilingual inscriptions ever found, currently examined by Adriano Maggiani and Gian Luca Gregori. Etruria has around thirty bilingual inscriptions, but most are funerary inscriptions. In this case, the monumental donation has a public character and mentions the sacred and hot source in Etruscan and Latin.

This is an extraordinary document that confirms the coexistence of different people at the sanctuary still at the beginning of the 1st century AD, with the need for divinity to be understood by all.

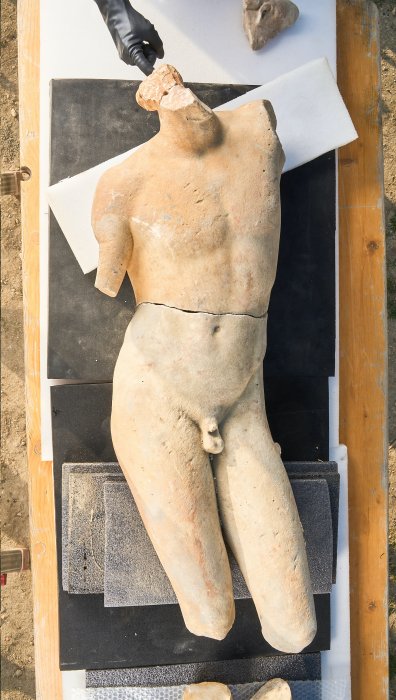

One of the most surprising discoveries occurred when archaeologists excavating inside the temple stumbled upon broken parts of a marvelous marble statue of a beardless, young Apollo with lizards.

The statue was broken when the sanctuary was closed at the beginning of the 5th century AD. In fact, this is when the entire place of worship was ritually closed, probably as a result of the widespread Christianization of the territory.

While the votive deposit was protected with the deposition of the large travertine columns that decorated the temple portico, the cult statue of Apollo was broken and fragmented.

The pieces were almost scattered and then covered by the embankments of the site’s abandonment. In parallel with what we still know and observe today – the “contestation of the statue” coincides with a moment of profound transformation and significant political and social questions.

Many examples of Apollo cults have been linked to thermal waters since archaic times. Apollo appears in San Casciano dei Bagni starting from 100 B.C. if we think of the dancing bronze statue with a bow placed in the oldest basin and exhibited in the Quirinale Palace.

The deity’s name occurs on at least two travertine altars from the Bagno Grande. Therefore, the marble statue adds a piece of the presence of the god but in a sanctuary which, at least from the 2nd century B.C. to the 3rd century A.D., was centered on the role of Apollo.

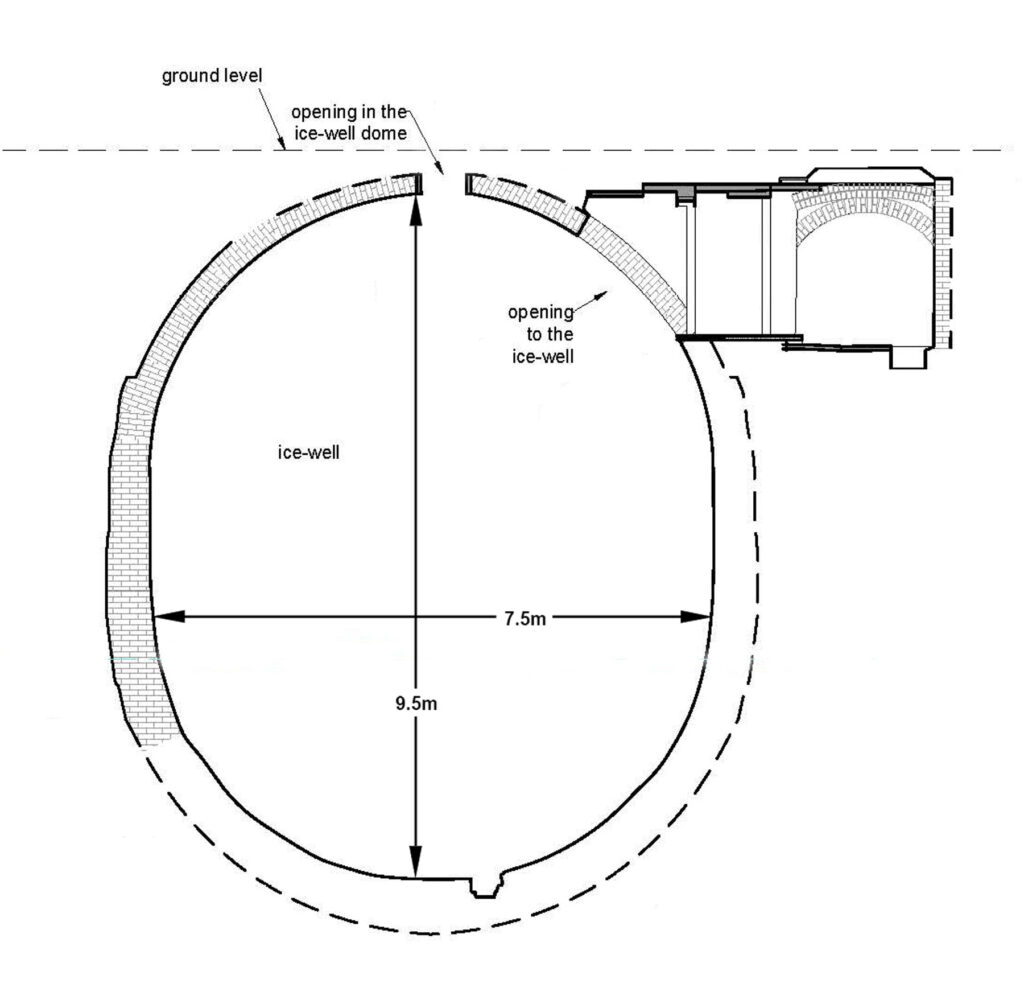

The archaeological excavation of the site covered approximately 400 m2, reaching a depth from the ground level in some points of over four meters.

Future digs will undoubtedly result in more exciting archaeological discoveries, shedding even more light on this fascinating ancient site.