Paleolithic ‘art sanctuary’ in Spain contains more than 110 prehistoric cave paintings

Archaeologists have discovered more than 110 prehistoric cave paintings and engravings dating to at least 24,000 years ago near Valencia, Spain.

The Paleolithic, or Stone Age, rock art is “arguably the most important found on the Eastern Iberian Coast in Europe,” the team said in a statement about the finding.

Locals and hikers have long known about Cova Dones (also spelled Cueva Dones), a 1,640-foot-long (500 meters) cave in the municipality of Millares. Although Iron Age finds were known from the cave, the Paleolithic artwork wasn’t documented until researchers discovered it in 2021.

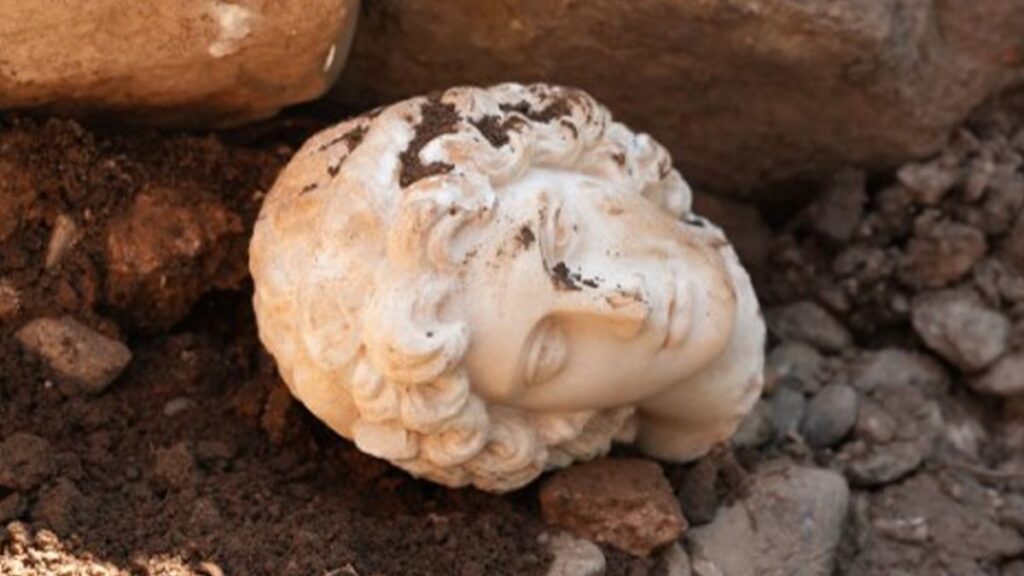

At first, the team found four painted motifs, including the head of an aurochs (Bos primigenius), an extinct cattle species. Additional work in 2023 revealed the site as a “major Palaeolithic art sanctuary,” the researchers wrote in a study published Sept. 8 in the journal Antiquity.

“When we saw the first painted auroch[s], we immediately acknowledged it was important,” Aitor Ruiz-Redondo, a senior lecturer of prehistory at the University of Zaragoza in Spain and a research affiliate at the University of Southampton in the U.K., said in the statement.

Spain has the most Paleolithic cave-art sites in the world, including the up to 36,000-year-old cave art at La Cueva de Altamira, but most are found in the northern part of the country, making the location of the new find unique. “Eastern Iberia is an area where few of these sites have been documented so far,” Ruiz-Redondo said.

The Paleolithic compositions stand out due to the sheer number of motifs and techniques used to make them.

The cave may even exhibit the most Stone Age motifs of any cave in Europe; the last big discovery of this kind was the finding of at least 70 cave paintings from up to 14,500 years ago at Atxurra in Spain’s northern Basque Country, in 2015.

In the new study, the researchers documented at least 19 depictions of animals, including horses, hinds (female red deer), aurochs and a stag.

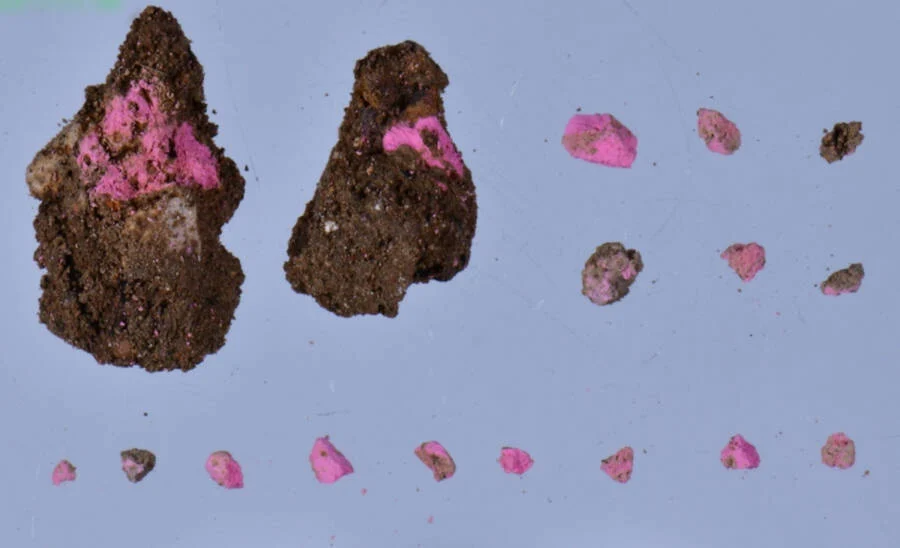

The other art includes signs like rectangles, isolated lines and “macaroni” shallow-groove lines made by dragging fingers or tools across a soft surface. Many of the motifs were made using red, iron-rich clay — a technique rarely seen in Paleolithic art, the researchers said.

“Animals and signs were depicted simply by dragging the fingers and palms covered with clay on the walls,” Ruiz-Redondo said.

The cave’s humid environment helped the paintings dry slowly, “preventing parts of the clay from falling down rapidly, while other parts were covered by calcite layers, which preserved them until today,” he said.

Some of the engravings were crafted by scraping limestone on the cave’s walls, the team added.

The investigations of the “rich graphic assemblage” are still in the early stages, as there are still more areas of the cave to survey and panels to document, the researchers wrote in the study.