Rare, 1,000-year-old Viking Age iron hoard found in a basement in Norway

A rare stash of 1,000-year-old ironwork, which sat for 40 years in a family’s basement in Norway, is now seeing the light of day after a woman discovered the hoard during some spring cleaning.

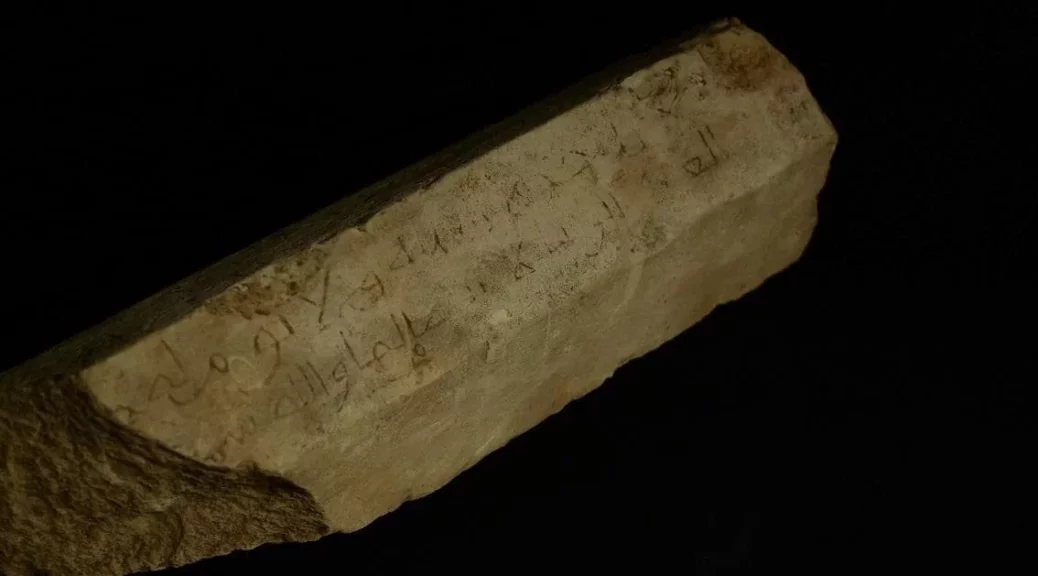

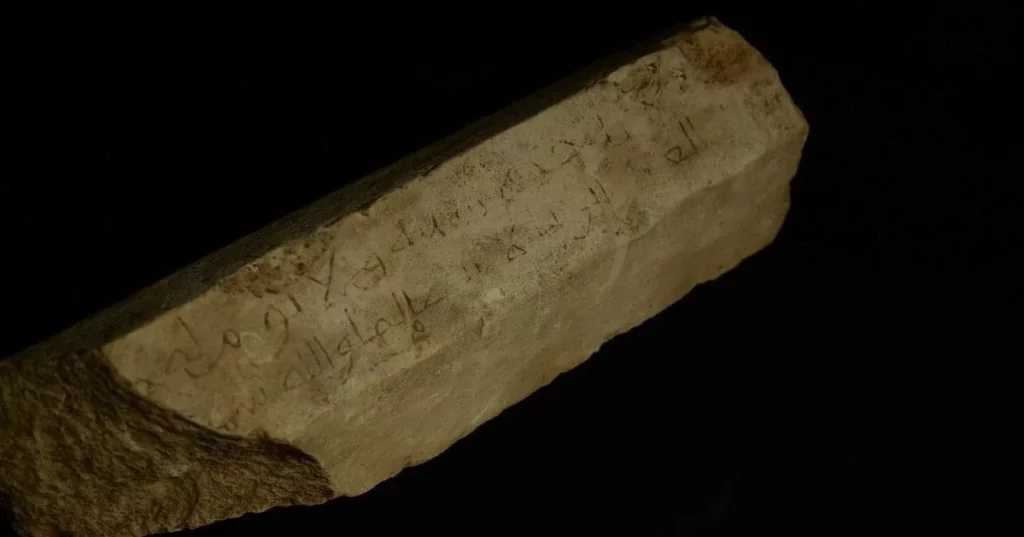

The hoard consists of 32 iron ingots that look like small spatulas and date back to the Viking Age (A.D. 793 to 1066) or the high Middle Ages (1066 to 1350). The rods are identical and weigh about 1.8 ounces (50 grams) each, prompting archeologists to think they may have been used as a form of currency and that someone probably buried them with the intention of coming back for the treasure later.

“We call it a cache find because it is clear that someone has [buried it] to hide it,” Kjetil Loftsgarden, an archeologist and associate professor at the University of Oslo and the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo, told NRK News. Each ingot is pierced with a hole on one end, which suggests the ingots could have been tied together in a bunch, experts added.

While similar ironwork already exists in the museum’s collections, this discovery is rare because construction projects often destroy or damage buried treasures, Loftsgarden said. In this case, Grete Margot Sørum, who came across the treasure trove while clearing out her parents’ basement in Valdres, central Norway, told NRK News that she remembers her father finding the stash while he dug a well by the house in the 1980s. “But then he put them away in a corner,” Sørum said.

The last time someone unearthed a hoard of iron ingots in Valdres was 100 years ago, according to NRK News.

From the late Viking Age until the high Middle Ages, independent farmers in southern Norway produced iron on a massive scale, according to a 2019 study by Loftsgarden, published in Fornvännen, the Journal of Swedish Antiquarian Research.

The region was so productive that there was a surplus of iron, which traders sold to elites in the more populated coastal regions of Norway.

Sørum’s father unearthed the ingots from a site located along the Bergen Royal Road, known as Kongevegen, which served as a trade route between Oslo and Bergen 1,000 years ago.

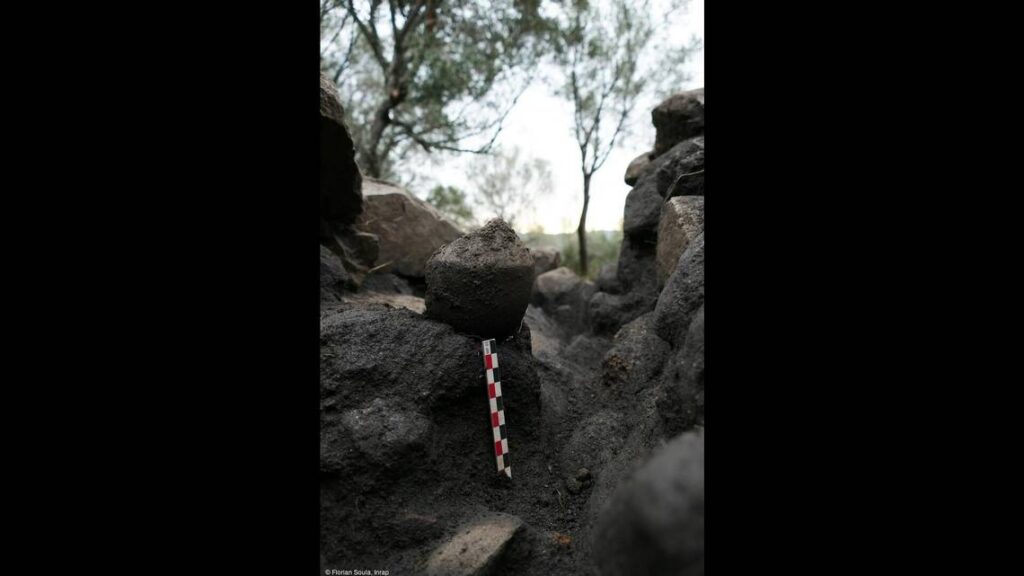

The area around the site was dotted with charcoal pits, which were indispensable to iron production for smelting during the Viking and Middle Ages, Loftsgarden wrote in the study.

Sørum notified the Valdres Folkemuseum in Fagernes, which then forwarded the iron collection to the Cultural Heritage section of the Innlandet county municipality. The iron hoard is now stored at the Cultural History Museum in Oslo, where archeologists will study and catalog the artifacts.

“Old finds that are handed into the archeologists provide new knowledge about the history of the Inland,” Anne Engesveen, unit leader for archeology at the Cultural Heritage section, said in a statement.

The discovery of the iron collection in the Sørum family basement is not the first Viking find from Norway in recent months. In November 2022, a metal detectorist stumbled across a Viking treasure hoard consisting of a pair of silver rings, fragments of a silver bracelet, and what look like chopped-up Arabic coins, among other buried artifacts.