Iznik Archaeology Museum reveals 2,500-year-old love letter

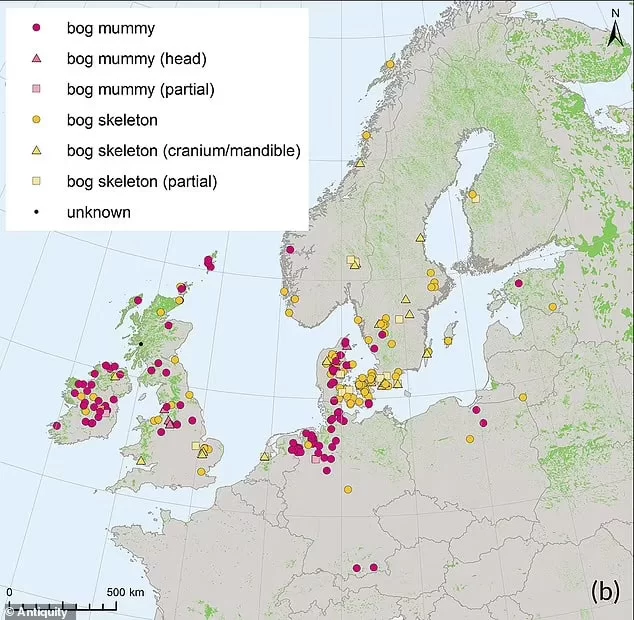

Iznik is an ancient habitation that hosts various civilizations due to its fertile lands, trade routes, and many other reasons.

Ancient Nicaea, now called İznik, is a farming town surrounded by massive medieval walls set on the shore of a broad lake 39 miles (63 km) southeast of Yalova. Two Christian ecumenical councils were held here, the 1st in 325, and the 7th in 787.

The seventh council took place at the Hagia Sophia Church, which is located in the heart of the city.

The historical city of Iznik, which has been the capital of four civilizations and a contender for UNESCO’s preservation list, is getting ready to open its Iznik Archaeology Museum and host special exhibitions of priceless antiquities.

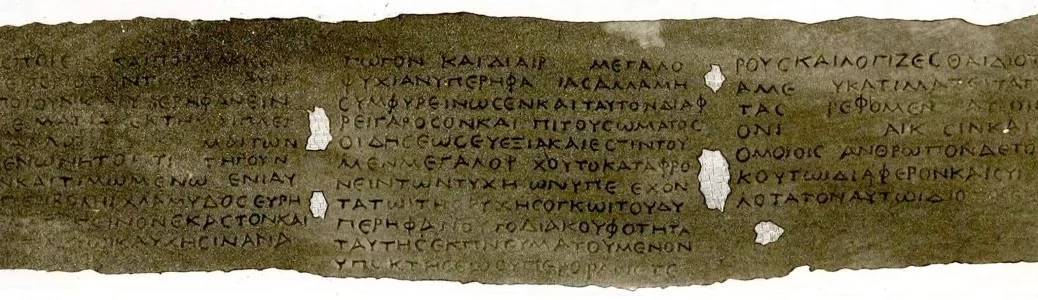

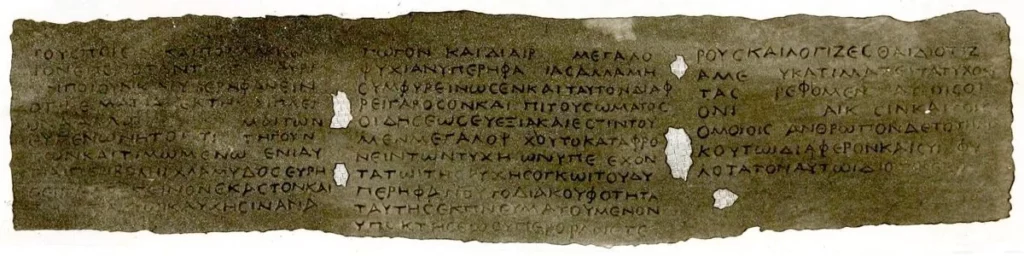

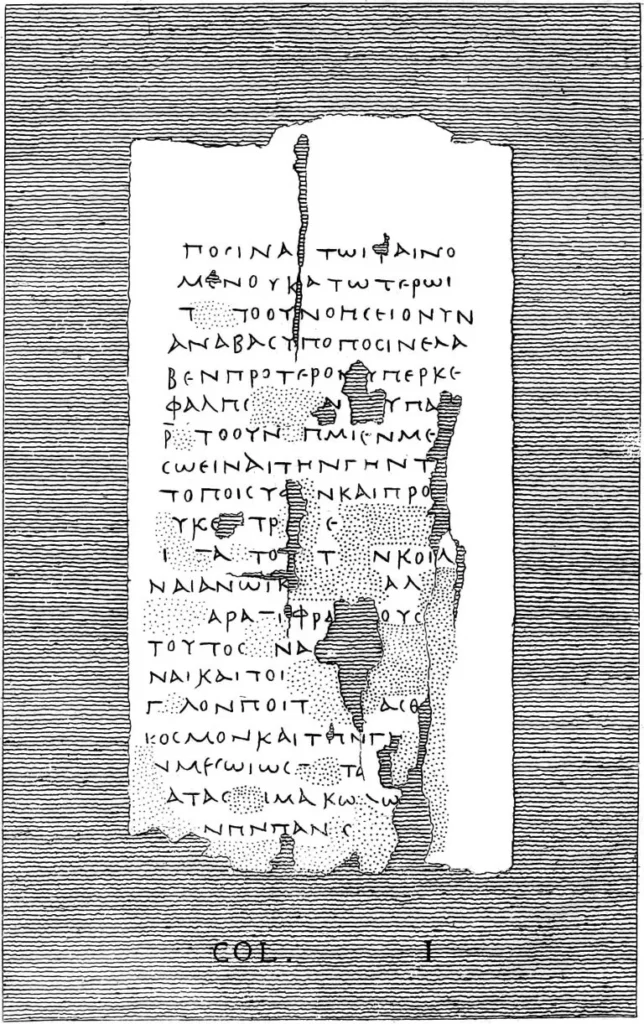

The museum has attracted the attention of many local and foreign tourists with its artifacts spanning a 5,000-year-old history. In particular, an ancient message engraved on the sarcophagus of Antigonus I, one of the generals of Alexander the Great, has aroused particular interest around the world.

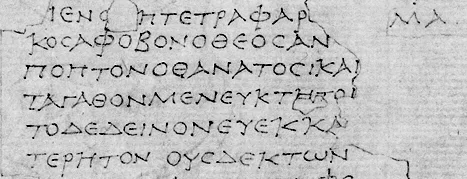

The emotional 2,500-year-old message, translated by expert archaeologists, reveals the grief over Antigonos I’s death.

“I, the sad Arete, cry out with all body and soul from the tomb of Antigonos. I pull my hair out from grief and I express myself by crying. This ill luck, the death, has captured me instead of emancipating this precious man,” the engraving reads.

Unsurpassed museum

The foundation of the Iznik Archaeology Museum was laid in 2020. With the completion of the construction, the museum’s inauguration ceremony is scheduled to take place shortly and surely will be one of the prominent museums of Europe with its rich data and ancient artifacts dating back to the Neolithic Age.

Speaking to Ihlas News Agency (IHA), former museum director and archaeologist Taylan Sevil said: “The new museum contains quite significant movable cultural assets.

There are artifacts of many civilizations from prehistoric times to the present. In that sense, the museum fills a huge gap here. It invites people to witness world civilization.”

The museum also has a marble board game from the Roman era, a sarcophagus of the Greek hero Achilles with spectacular engravings, and sarcophagi of Antigonos I and noble families with dazzling engravings.