Archaeologists discovered an enigmatic complex of rooms, the interiors of which were covered with figural scenes unique to Christian art

Archaeologists of the Polish Center of Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of Warsaw discovered an enigmatic complex of rooms made of sun-dried brick, the interiors of which were covered with figural scenes unique to Christian art.

The discovery was made at the Old Dongola medieval monastery on the banks of the Nile, more than 500 km north of Khartoum.

Old Dongola (Tungul in Old Nubian) was the capital of Makuria, one of the most prominent medieval African states. It had converted to Christianity by the end of the sixth century, but Egypt was conquered by Islamic armies in the seventh century.

An Arab army invaded in 651 but was repulsed, and the Baqt Treaty was signed, establishing relative peace between the two sides that lasted until the 13th century.

The discovery was made during the exploration of houses dating from the Funj period (16th-19th century CE). Within the main monastic complex, the Polish mission unearthed now a second, well-preserved church with vivid mural paintings and inscriptions in Greek and Old Nubian.

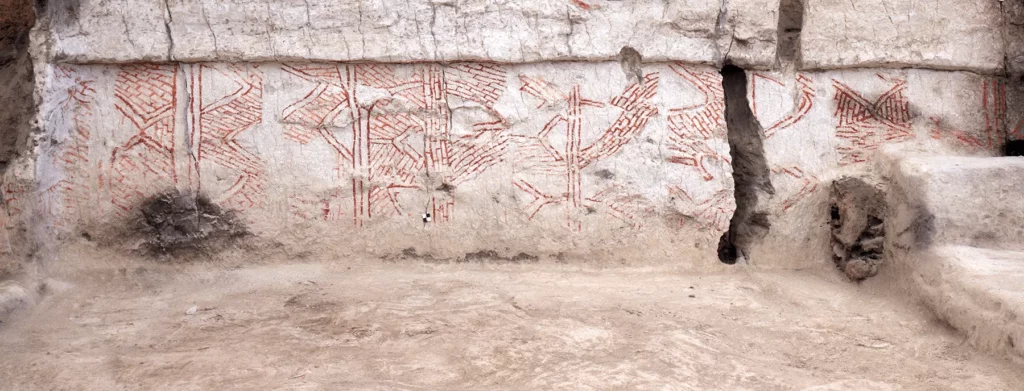

Surprisingly, beneath the floor of one of the houses was an opening leading to a small chamber with walls decorated with unique representations.

The paintings inside depicted the Mother of God, Christ, and a scene with a Nubian king, Christ, and Archangel Michael. This was not, however, a typical depiction of a Nubian ruler under the protection of saints or archangels.

The king bows and kisses the hand of Christ, who is seated in the clouds. The ruler is aided by Archangel Michael, whose spread wings protect both the king and Christ. Such a scene finds no parallels in Nubian painting.

The representation’s dynamism and intimacy contrast with the hieratic nature of the figures depicted on the side walls. Similarly, the figure of the Virgin Mary on the north wall of the chamber does not fit into the standard repertoire of Mary depictions in Nubian art.

The Mother of God is dressed in dark robes and strikes a dignified pose. She has a cross and a book in her hands. On the opposite wall, Christ is depicted. His right hand is shown in a blessing gesture, and his left hand is holding a book, which is only partially preserved.

Dr. Agata Deptua of PCMA UW is currently studying the inscriptions that accompany the paintings. A preliminary reading of the Greek inscriptions revealed that they were texts from the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts.

The main scene is accompanied by an inscription in Old Nubian that is extremely difficult to decipher. The researchers learned from a preliminary reading by Dr. Vincent van Gerven Oei that it contains several references to a king named David as well as a prayer to God for the protection of the city.

The city mentioned in the inscription is most likely Dongola, and the royal figure depicted in the scene is most likely King David. David was one of Christian Makuria’s last rulers, and his reign signaled the beginning of the kingdom’s demise. For unknown reasons, King David attacked Egypt, which retaliated by invading Nubia, resulting in Dongola being sacked for the first time in its history.

Researchers think that the painting may have been made while the Mamluk army was approaching or the city was under siege.

The complex of rooms where the paintings were discovered, however, is what stumps people the most. The actual spaces, which are made of dried brick and covered in vaults and domes, are quite small. Although the painted room that depicts King David is seven meters above the medieval ground level, it looks like a crypt.

The structure is next to a sacred structure known as the Great Church of Jesus, which was likely Dongola’s cathedral and the most significant church in the Makurian kingdom.

According to Arab sources, the Great Church of Jesus instigated King David’s attack on Egypt and the capture of the ports of Aidhab and Aswan.

These and other inquiries about the enigmatic structure may be answered by further excavations. However, safeguarding the distinctive wall paintings was the main goal for this season. Following the discovery, conservators got to work under the supervision of Magdalena Skaryska, MA.

The Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, the University of Warsaw, and the Department of Conservation and Restoration of Works of Art of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw collaborated to operate the conservation team.