Human ‘bog bones’ discovered at a Stone Age campsite in Germany

Archaeologists in northern Germany have unearthed 10,000-year-old cremated bones at a Stone Age lakeside campsite that was once used for spearing fish and roasting hazelnuts, major food sources for groups of hunter-gatherers at that time.

The site is the earliest known burial in northern Germany, and the discovery marks the first time human remains have been found at Duvensee bog in the Schleswig-Holstein region, where dozens of campsites from the Mesolithic era or Middle Stone Age (roughly between 15,000 and 5,000 years ago) have been found.

Hazelnuts were a big attraction in the area because Mesolithic people could gather and roast them, Harald Lübke, an archaeologist at the Center for Baltic and Scandinavian Archaeology, an agency of the Schleswig-Holstein State Museums Foundation, told Live Science.

The campsites changed over time, the research shows. “In the beginning, we have only small hazelnut roasting hearths, and in the later sites, they become much bigger” — possibly a consequence of hazel trees becoming more widespread as the environment changed.

The burial was found during excavations earlier this month at a site first identified in the late 1980s by archaeologist Klaus Bokelmann and his students, who found worked flints there not during a formal excavation, but during a barbecue at a house on the edge of a nearby village, Lübke said.

“Because the sausages were not ready, Bokelmann told his students that if they found anything [in the bog nearby], then he would give them a bottle of Champagne,” he said. “And when they came back, they had a lot of flint artifacts.”

Ancient lake

The burial site is near at least six Mesolithic campsites, which would have been on the shores of the ancient lake at Duvensee, Lübke said.

The first sites investigated by Bokelmann in the 1980s were on islands that would have been near the western shore of the lake, which has completely silted up over the last 8,000 years or so, and formed a peat bog, called a “moor” in Germany.

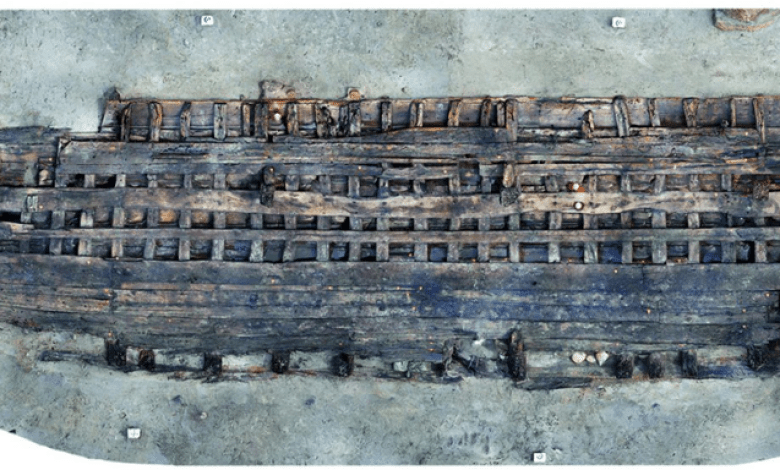

Archaeologists have discovered mats made of bark for sitting on the damp soil, pieces of worked flint, and the remains of many Mesolithic fireplaces for roasting hazelnuts, but they haven’t unearthed any burials at the island sites.

“Maybe they didn’t bury people on the islands but only at the sites on the lake border, which seem to have had a different kind of function,” Lübke said.

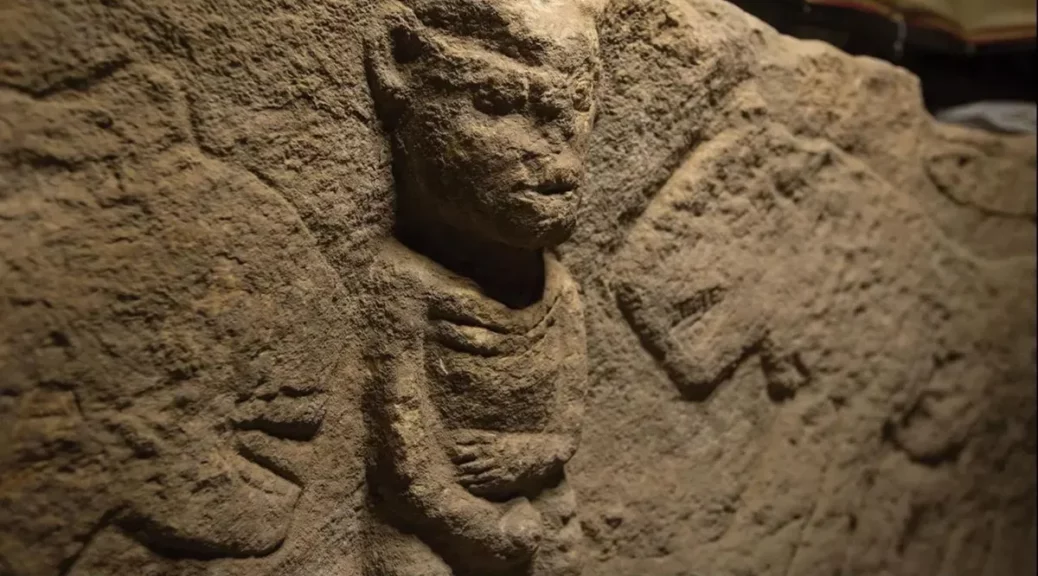

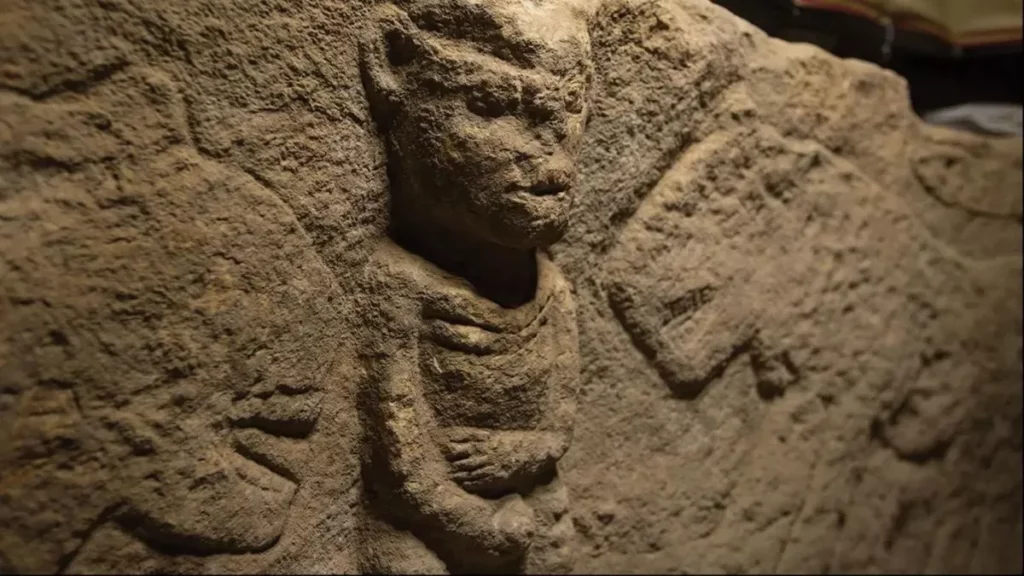

Unlike during the later Mesolithic era, when specific areas were set aside for the burial of the dead, at this time it seemed the dead were buried near where they died, he said. Significantly, the body was cremated before its burial at the Duvensee site, like other burials of approximately the same age near Hammelev in southern Denmark, which is about 120 miles (195 kilometers) to the north.

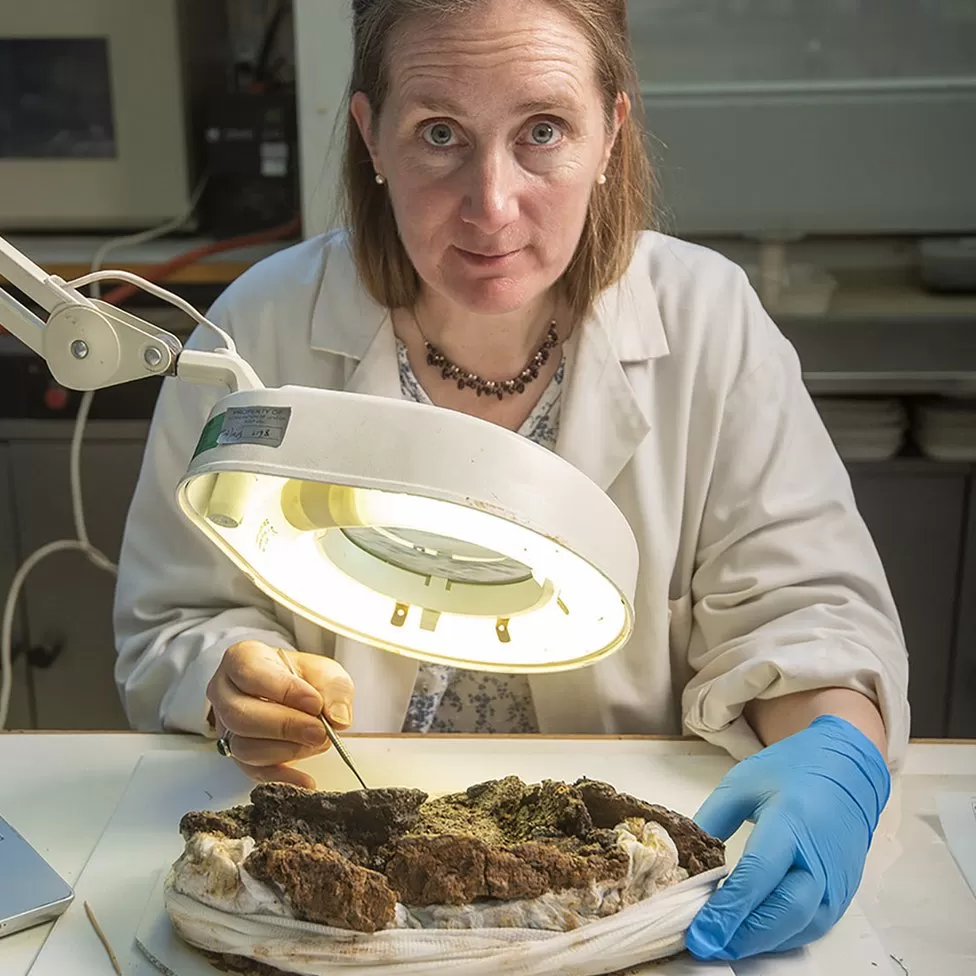

Only pieces of the largest bones were left after the cremation, and it’s not clear if they were wrapped in hide or bark before they were buried. In any case, “burning the body seems to be a central part of burial rituals at this time,” Lübke said.

Changing landscape

As well as roasting hazelnuts and burning bodies — both of which are activities utilizing fire — Mesolithic people used the lakeside campgrounds for spearing fish, according to the discovery of several bone points crafted for that purpose that were found at the site.

Flint fragments also have been found throughout the area, although flint doesn’t occur naturally there, suggesting that Mesolithic people repaired their tools and hunting weapons in this place during the annual hazelnut harvest in the fall, Lübke said.

The Mesolithic sites at Duvensee are about the same age as the Mesolithic site at Star Carr in North Yorkshire in the United Kingdom, and some of the artifacts found there are very similar, Lübke said.

From that time until about 8,000 years ago, the Schleswig-Holstein region and Britain were connected by a now-submerged region called Doggerland, and it’s likely that Mesolithic groups would have shared technologies, he said.

The researchers now plan to carry out further excavations at the site of the Mesolithic burial, to determine what other activities took place there.

Ulf Ickerodt, head of Schleswig-Holstein’s State Archaeology Department, said the latest find at Duvensee is of global significance.

“It speaks to the long tradition of archaeological research in Schleswig-Holstein in the expiration of moors and wetlands,” he told Live Science in an email. “The present find advances itself and the landscape around it to something spectacular.”

But he noted that the preservation of organic finds in the Duvensee region is threatened by climatic changes that could result in heavy rain and flooding, or dry periods.

Both types of changes could threaten archaeological features in the area, so archaeologists are working to recover any finds and to develop strategies for better managing the area in the face of a changing climate, Ickerodt said.