Polish archaeologists co-discover ‘unique’ Roman military tower

A Polish-Maroconian team of archaeologists have discovered a Roman military observation tower in Volubilis, Morocco. ‘This is important for research on the system of Roman fortifications built on the outskirts of the empire’, says Maciej Czapski, an archaeologist from the University of Warsaw.

Similar military observation towers had been previously discovered during excavations in Scotland, Germany, and Romania, but never in Morocco.

From the 5th decade CE, Morocco was part of the Roman Empire, but since it was geographically isolated, from a scientific point of view little is known about this region and archaeologists treat it as a niche.

‘Based on satellite images, we have selected several sites that have a common feature: an oval plan with an inscribed rectangle or square. We have chosen this particular site because it is located farthest to the south. There are a few brief descriptions of this site in French publications indicating that the place could have been associated with the Roman army’, says Czapski.

The researcher adds that preparations for excavations included dozens of hours spent in libraries in Rimini and London but this and the analysis of satellite images did not guarantee success.

“We were lucky to have started digging in the right place. Just a 500-600 m shift of the starting point would have resulted in finding nothing. Our discovery is a significant contribution to the general state of research on the Roman limes – the system of Roman border fortifications, erected on the outskirts of the empire, especially vulnerable to raids’, says Czapski.

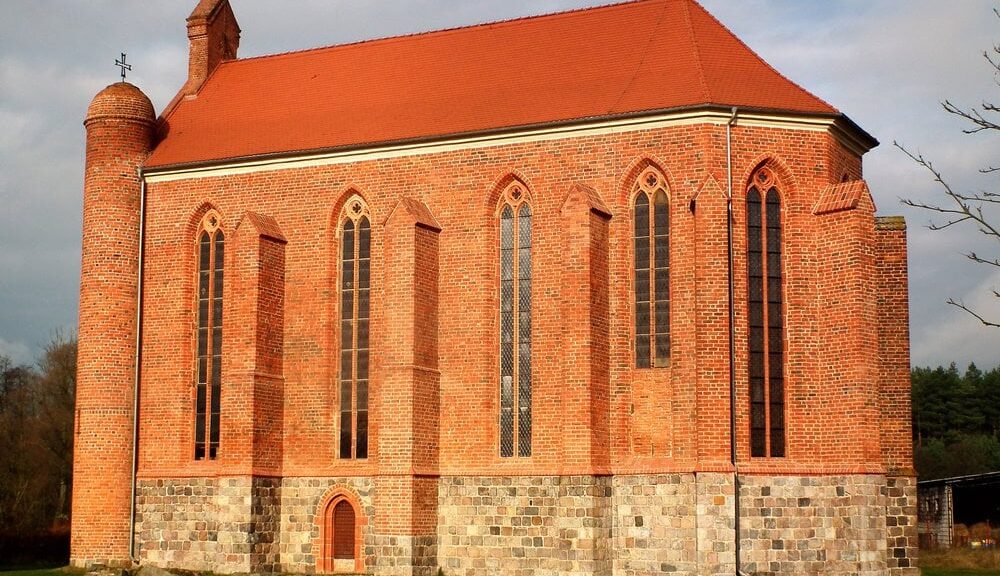

Included amongst the find were the foundations and fragments of walls preserved up to a height of approx. 80 cm. A fragment of the internal staircase and a fragment of cobblestones surrounding the building on the south side have also been preserved. The outer wall has not survived. Tile fragments are in very bad condition.

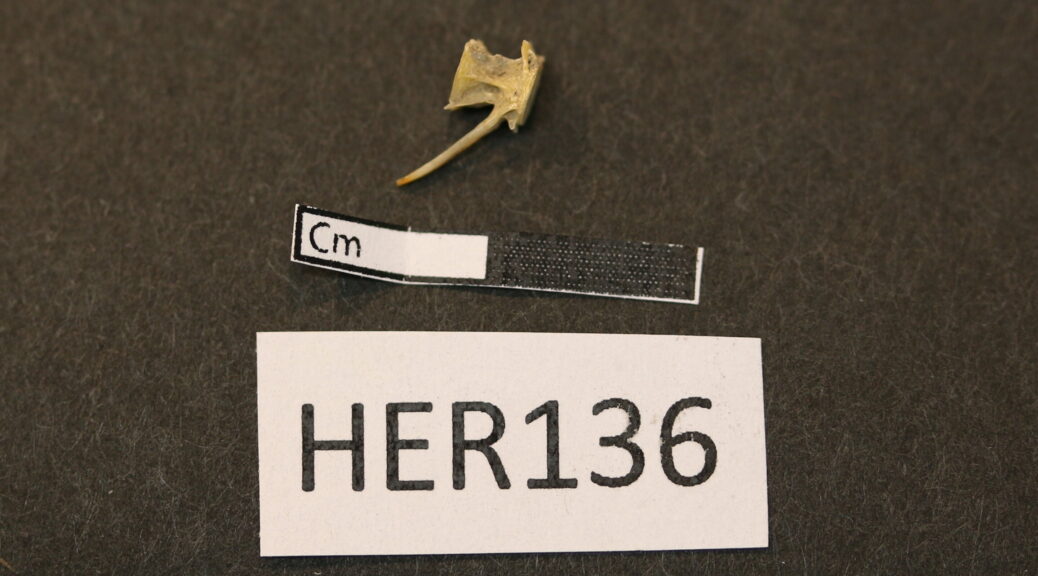

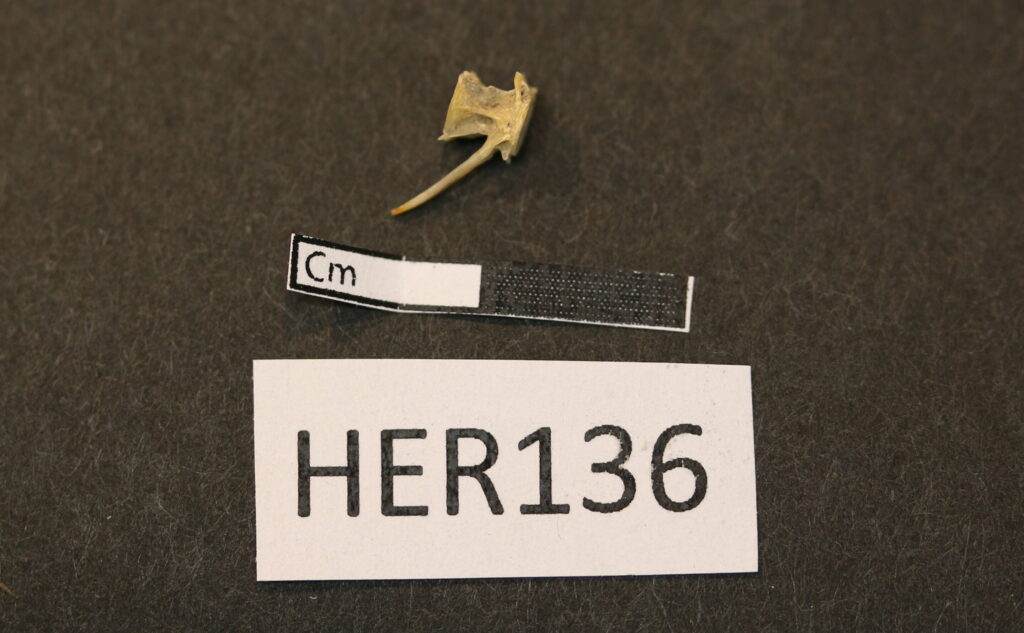

The researchers also found fragments of weapons and accessories of Roman legionnaires.

“We found fragments of javelins, nails from sandals of Roman legionnaires, fragments of ornaments typical for Roman military belts,” says Czapski.

“Until now, we had a very broad dating – we knew that there was a defence system of the Roman province between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE. We want to narrow down the chronology and explain whether it was a single system or different systems at different times. We have a hypothesis that the system we discovered existed during the reign of Antoninus Pius. We have some military finds dating back to this period, around the 2nd century CE,” says Czapski.

He adds that “a lot is known about the military and political situation of this region. We know that battles were fought, but we do not know the details – what their course was, whether they were very heavy, and to what extent. We know that in some cases it ended with signing treaties as a result of diplomatic activities, but we do not know the details.”

The main focus of the Polish-Moroccan team is determining how the Romans maintained the acquired territories and what were their contacts with the local population.

“We are dealing with the relations between the administration and the local population. We know that these relations were quite turbulent because epigraphic evidence confirms it. We want to find out how the Romans controlled the flow of people and goods, that is, how they controlled the border zone’, says Czapski.

The head of the Polish part of the research team Dr. Radosław Karasiewicz-Szczypiorski from the University of Warsaw, and the Moroccan team leader is Professor Aomar Akerraz from the National Institute of Archaeology and Cultural Heritage (INSAP) in Rabat. The team consists of 10 people.

In the near future, the researchers plan to complete the documentation and publish a report. Next year, after the end of Ramadan, they will begin field work at a different site. They hope to discover more towers, which would help to “complete the concept of the Roman defence system.

“Next year, at the turn of May, we will dig at a different site. The discovery of another tower should be easier. We now know where to dig and what to expect,” says Czapski.