The Guadeloupe Woman: A Human Skeleton Dating Back 28 Million Years

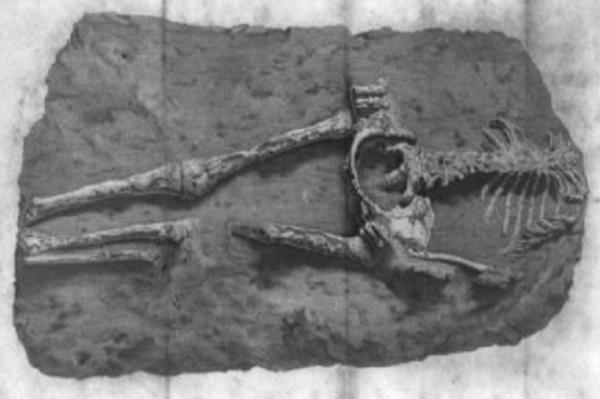

In 1810 the British seized the French Island of Guadeloupe and sent a large stone slab back to England containing a skeleton of a headless and footless woman. This particular skeleton has become the object of controversy regarding the age of the skeleton and the Creation debate. We will discuss this skeleton and add to this debate.

We came across this oddity when reading the website Bad Archaelogy.wordpress.com written by Keith Fitzpatrick Matthews, an English archaeologist. Frankly, his precision and attention to specific detail regarding the skeleton were refreshing even though they demonstrated a traditional and narrow perspective. We understand that science must be rigorous.

We also understand that it is necessary for science to disprove various theories in order to get to an accurate and truthful assessment of any object, artefact, or skeleton. However, narrowness and rigid adherence to traditional methodologies do not guarantee correctness. Since science, itself, is an exercise in probabilistic truth; it can’t guarantee certainty.

So, what do we have? Well, we have a skeleton found in a slab of rock one mile long with an unknown date of origin. Matthews states that the original investigator declared the stone to be a kind of sandstone made up of a concretion of calcareous sand. Well, so far so good. Additionally, Matthews tells us that there is a graveyard near the site of the skeleton’s excavation began at the time of Columbus’ discovery of the island in the Caribbean in 1493.

Therefore, he believes this skeleton is not of Miocene age, 28 million to 5 million years old, but of a recent date, possibly in the 15th century.

Now, this skeleton may indeed be a 15th-century skeleton. However, it is not proven to be so. It still could be of a much older age even 28 million years old.

This skeleton’s age may not be “discredited” at all because of the probabilistic nature of science and the fact that a modern age has not been proven either. To properly determine its age one would have to examine the geology of the matrix surrounding the skeleton, examine the skeleton, itself, and properly study the geology of the island of Guadeloupe. To the best of my knowledge, none of these things has been done. So, there is a real lack of evidence on the side of traditional “mainline” archaeology to support a claim of a recent, 15th century, the age for this skeleton.

Now, can we find any other evidence to support a claim of an older age? Yes! First, the skeleton was embedded in rock. This is a process that takes some time. Second, we can consider a new technique, one that I have pioneered, that is the use of plate tectonics – the movement of the continental plates.

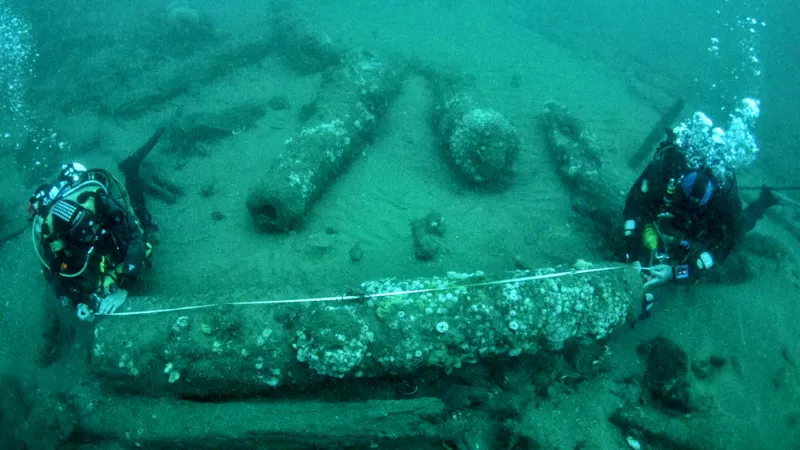

If we do this we arrive at an unexpected surprise. Guadeloupe, as with all the islands of the West Indies rests on the Caribbean plate and neither on North America nor South American plates.

This means if we extend the location of Guadeloupe backward in time we find that at the end of the Cretaceous Period, 66 million years ago, it was located south to southwest of the Yucatan.

With the meteorite impact that killed the dinosaurs, a huge tidal wave of 1100 feet in height flooded all of Mexico and the surrounding area and could have carried the bodies of individuals to Guadeloupe.

A closer look at the eastern side of the island shows an indentation that could have been caused by this tidal wave. Of course, additional geological research is needed to confirm this.

So, we claim that the skeleton has not been discredited until further research is done. Furthermore, the fact of the Caribbean plate movements due to place Guadeloupe much closer to the Yucatan opens the door to the possibility that the skeleton maybe not be 28 million years old but 66 million years old. The question is still open.

Author’s Note: There is an impact crater in the Chesapeake Bay in the state of Virginia that is 35 million years old. The crater is 53 miles wide and fractured the Earth to a depth of between 6 to 12 miles. This impact could have resulted in a massive tidal wave that carried the Guadeloupe Woman to her present resting place.