Norway’s Medieval Monks Discussed Their Meals in Silence

Mealtime peace is a well-known concept in many Norwegian homes: You should sit still at the table and enjoy the food you are served. Monks back in the day took this to a new level. Speaking during meals was forbidden, and so a new sign language was born.

The monastery on a small Oslo island

Marianne Vedeler is a professor of Archeology at the Museum of Cultural History. She says that the silent meals took place on Hovedøya, a small island in the Oslofjord.

“A small group of monks came here in the 12th century. They had travelled from Kirkstead in England and wanted to establish a monastery here in Norway. They were Cistercian monks and had a very strict monastic order,” she says.

The rules covered all aspects of how they should live and were regulated down to how much bread they could eat per day.

“The rules were written down, so we know a lot about how these monks lived in the Middle Ages,” Vedeler says.

The regulations for Cistercian monks were international and thus followed them to Hovedøya in Oslo.

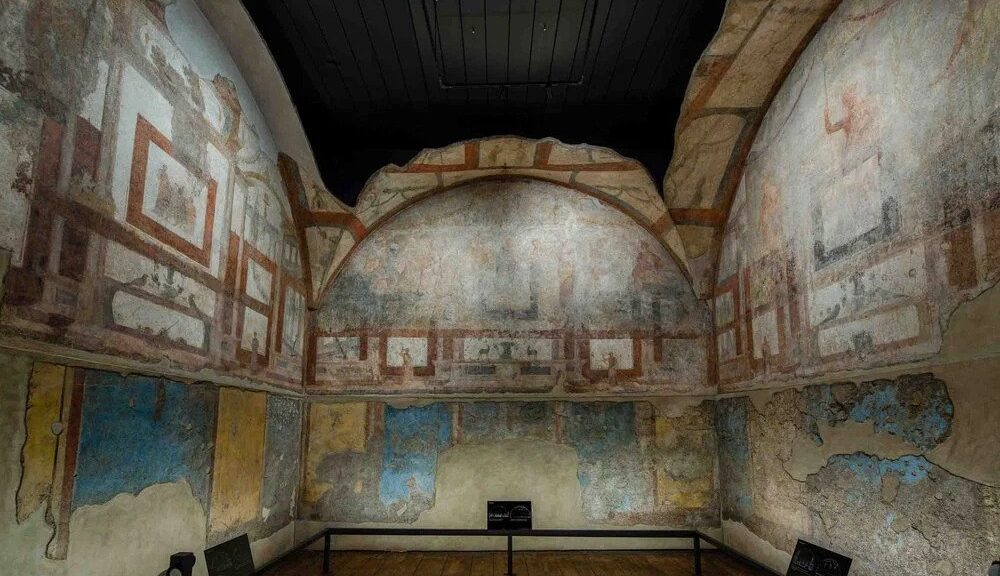

“Here they were to live like the Cistercian monks in monasteries in France and England. And the monasteries were to be designed according to the same template,” Vedeler says.

She has examined ruins, food remains, and fish bones that remain after the monks on the island Hovedøya.

Silent since the 6th century

The Monastic monks’ motto was “Ora et labora” – to pray and work. This was to occupy most of the day. It was generally desirable to minimise talking as much as possible. Their thoughts were to be turned towards God.

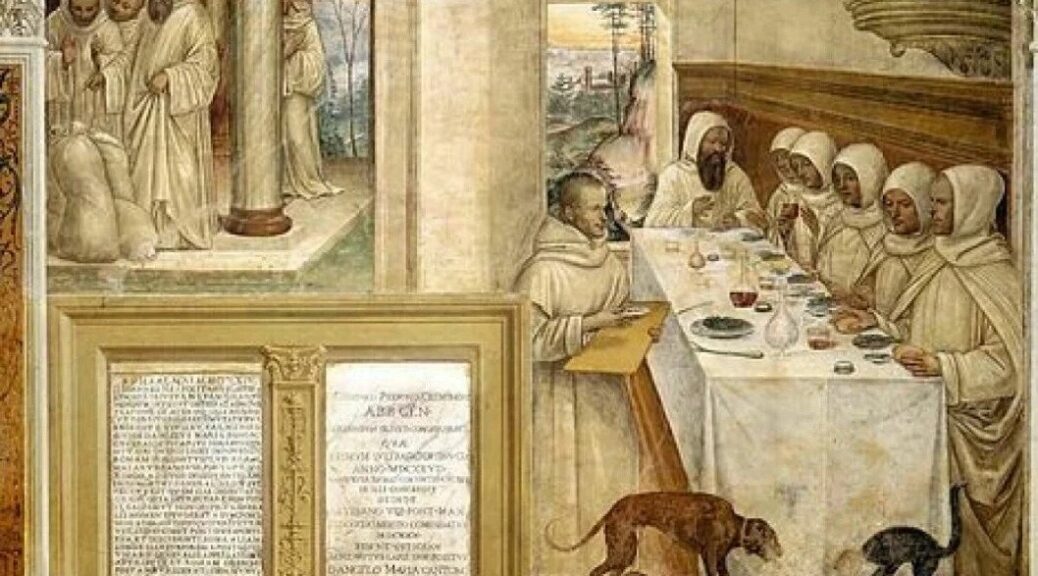

The two daily meals were also important. Everyone sat on one side of the table. By doing this, they avoided a possible conversation partner in front of them.

According to an article in the scientific journal Gastronomica, the rules of silent meals were introduced as early as the 6th century with ‘The Rule of Saint Benedict’. Saint Benedict encouraged the monks to communicate in other ways than using their voices during meals.

To accomplish this, monks at the mighty and prosperous Monastery of Cluny in France began remaining silent throughout their meals. The article in Gastronomica makes references to a biography in which Vikings captured a group of monks that they tried to force to speak. They were unsuccessful.

Monk sign language

Vedeler says that the ban on talking may have led to the monks enjoying their meals more. It was important for the monks to find a place to live where they could sustain themselves by fishing and growing fruit and vegetables. They were pescatarians and ate seafood in addition to a largely vegetarian diet.

“This is why Hovedøya was an ideal place to set up the monastery,” she says.

In addition to what could be captured in the sea, the monks constructed a fish farm on land where they could keep freshwater fish. These species of fish have their own specific signs in the sign language.

Kirk Ambrose, a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, has created a list of how different foods were communicated through sign language. The monks had signs for, amongst other things, honey, beans, eggs, and seven different species of fish.

To signal fish, the monks moved their hands like a fishtail in water. For squid, they would spread their fingers and wave them. If you wanted an eel, your hands had to be held together as if you were holding an eel. Pike could be communicated using the same sign as for fish, but with a faster movement because the pike is a fast swimmer.

Ambrose further writes that some of the signs are used by Cistercian monks even to this day.