Ritual site of a Mesopotamian god of war found in Iraq that was used for animal sacrifices

Archaeologists have discovered 5,000-year-old sacred places in Iraq for 5,000 years which have been used for rituals intended to appease a Mesopotamian warrior god.

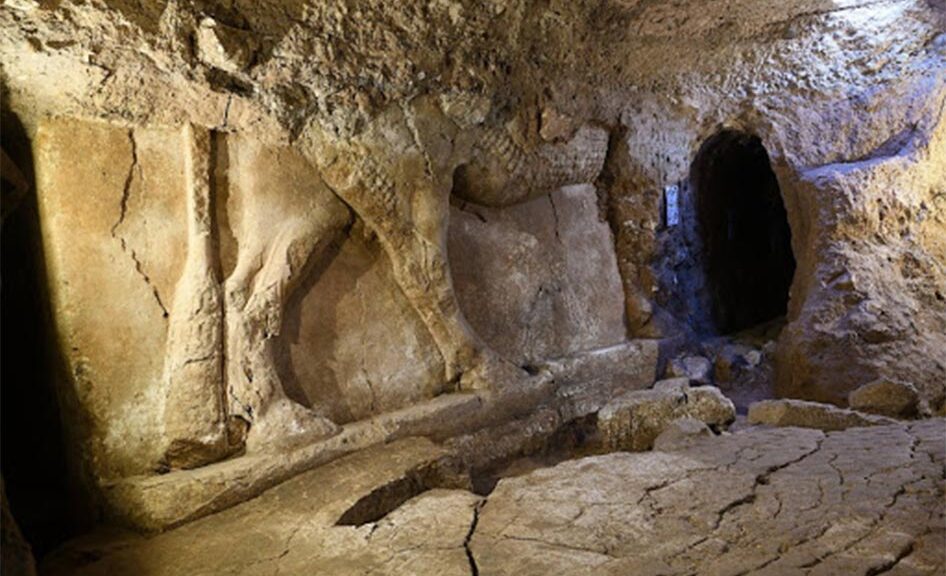

The team working at the Telloh site believes it was used for parties, animal sacrifices and other processions dedicated to Ningirsu – the hero-god of war, hunting and weather.

Next to the pit were cups, bowls, jars and animal bones which, according to experts, are the remains of animal sacrifices. However, a bronze duck-shaped object was also discovered that may have been dedicated to Nanshe, a goddess associated with water, swamps and water birds, LiveScience reported. The ritual site is located in what was once Girus, which was the city of ancient Sumer, one of the first cities in the world.

A sacred place has been hidden in Iraq for 5,000 years and has been used for rituals to appease a Mesopotamian warrior god and a recent excavation has exposed its horrible past. Archaeologists working at the Telloh site have discovered that the area was used for festivals, animal sacrifices and other processions dedicated to Ningirsu – the hero-god of war, hunting and weather

The area has been of interest to archaeologists for years, as it is home to important Sumerian remains and artefacts. Recently, experts have investigated the centre of Girsu where the Ningirsu temple once stood.

Here they found more than 300 ceremonial ceramic cups, bowls, jars and beakers, all of which have been damaged over time. There was also a treasure trove of animal bones hidden under the dirt, which archaeologists say are remains of the animal sacrifices held in the ritual pit.

Here they found over 300 ceremonial ceramic cups, bowls, jars and beakers, all of which have been damaged over time. There was also a treasure trove of animal bones hidden under the dirt, which archaeologists believe to be the remains of animal sacrifices held in the ritual pit

The city was used about 5,000 years ago to appease a Mesopotamian god of war. A bronze figurine that looks like a duck has also been discovered, which the team, who told LiveScience in an email, believe they were dedicated to Nanshe, a goddess associated with water, swamps and water birds, as well as a vase engraved with text on the goddess.

Sébastien Rey, director of the Tello / Ancient Girsu project at the British Museum, and Tina Greenfield, a zooarchaeologist at the University of Saskatchewan, led this excavation at the site.

The area has been of interest to archaeologists for years, as it is home to important Sumerian remains and artefacts. Experts recently investigated the centre of Girsu, where the Ningirsu temple once stood

The ritual site is located in what was once Girus, which was the city of ancient Sumer – one of the first cities in the world. Because a thick layer of ash was found on the ground, the team speculates that massive parties have taken place in the area.

These clues link the region to the place “where, according to cuneiform texts, religious festivals were held and where the people of Girsu gathered to feast and honour their gods,” said Rey and Greenfield in the email.

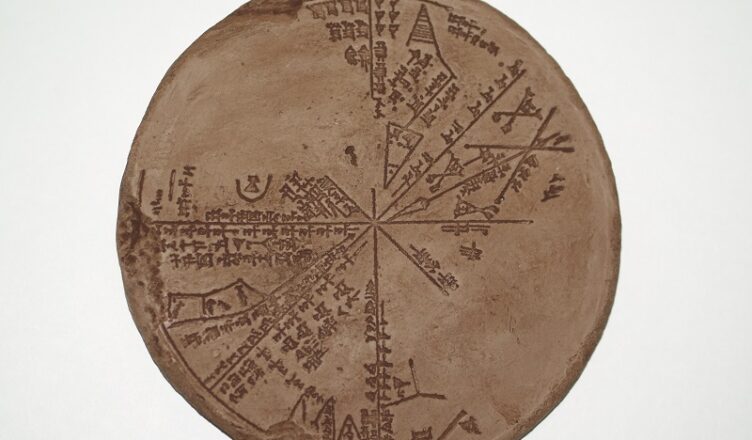

Clay tablets, also known as cuneiform tablets found in Girsu, depict residents holding religious ceremonies in the sacred square. The text tells of a religious celebration in honour of Ningirsu that took place twice a year and lasted three or four days, said Rey and Greenfield.

WHAT IS OLD MESOPOTAMIA?

A historic area of the Middle East that covers most of what is now known as Iraq, but which also extends to include parts of Syria and Turkey. The term “Mesopotamia” comes from Greek, which means “between two rivers”.

The two rivers to which the name refers are the Tiger and the Euphrates. Unlike many other empires (such as the Greeks and Romans), Mesopotamia was made up of many different cultures and groups.

Mesopotamia should be better understood as a region which has produced several empires and civilizations rather than any civilization. Mesopotamia is known as the “cradle of civilization” mainly due to two developments: the invention of the “city” as we know it today and the invention of writing.

Mesopotamia is an ancient region of the Middle East that is most of modern Iraq and parts of other countries. They invented cities, the wheel and agriculture and gave women almost equal rights

Thought to be responsible for many early developments, he is also credited with the invention of the wheel. They also gave the world the first massive domestication of animals, cultivated large tracts of land, and invented tools and weapons.

In addition to these practical developments, the region has seen the birth of wine, beer and the delimitation of time in hours, minutes and seconds. The fertile land between the two rivers is believed to have provided a comfortable existence for hunter-gatherers which led to the agricultural revolution.

A common thread throughout the region is the equal treatment of women. Women enjoyed almost equal rights and could own land, file for divorce, own their own business, and enter into commercial contracts.