Did the Celts build “America’s Stonehenge” 4,000 years ago?

Studying the origins of the aptly named Mystery Hill megaliths, also known as America’s Stonehenge, whets one’s curiosity but does not satisfy—unless one is satisfied by the excitement of confounding mystery alone.

The site, in North Salem, N.H., includes stone monoliths and chambers spread across 30 acres. The stones are said to have complex astronomical alignments. A 4.5-ton stone slab that seems to be the focal point of the site may have served as an altar for sacrifice. It is grooved with a channel for draining, possibly the blood of a victim.

A variety of characteristics have fueled a theory that America’s Stonehenge was built by Europeans as long ago as 2,000 B.C.—thousands of years before the first evidence of Viking settlement in North America. Archaeologists are divided. Some say the evidence is lacking to support this theory and that the site may have been constructed in relatively recent times.

Many similar sites are found on the stretch from Maine to Connecticut, though none as expansive as Mystery Hill. Here’s a look at the site’s characteristics and the views of various experts.

Why it May Have Been the Celts

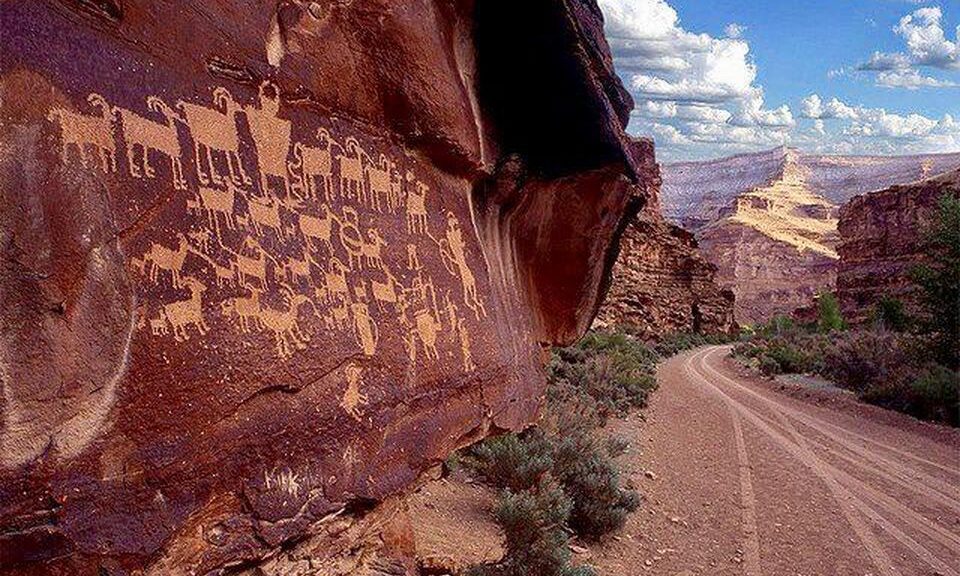

1. Glyphs seem to suggest an archaic Irish language, though any deciphering of the glyphs has been controversial.

2. It seems from the astronomical alignment that the megaliths mark cross-quarter holidays. These holidays are only celebrated by the Celts, according to astronomer Alan Hill. Some have compared the megaliths to Stonehenge.

3. “Carbon-14 results coincide with the date of a major immigration by Celts,” according to a book by David Goudsward and Robert Stone titled “America’s Stonehenge: The Mystery Hill Story, from Ice Age to Stone Age.” Stone bought the site in the 1950s and opened it to public viewing and to further research. Goudsward and Stone continue: “The Celtiberians [Celtic-speaking people of the Iberian Peninsula] interacted with Carthaginians, a nationality almost certain to have the skill to cross the Atlantic. However, there is not of the ornamentation on the stones that would be indicative of Celts.”

Why it May Have Been the Natives

1. Archaeologists have found Native American artefacts on-site that are more than 1,000 years old.

2. The use of stone-on-stone tools shows workmanship similar to that employed by Native Americans.

Glyphs of the Celts?

Ogham is an Irish script used in the fifth to sixth centuries that consists of crosshatches. Glyphs that may be ogham are said to have been found on the stones.

Karen Wright, who wrote an article for Discovery Magazine in 1998 after visiting Mystery Hill, described what she felt to be dubious deciphering: “Various authors [have made interpretations,] consulting languages from ogham to Russian. The most baroque interpretation, a translation based on Iberic/Punic, was ascribed to three evenly spaced parallel grooves in a rust-coloured cast: ‘In Baal, on behalf of the Canaanites this is dedicated,’ read the translation.

“This, I decided, was the archaeological equivalent of the scene from Lassie in which the dog barks once and Jimmy is given to understand that the leg of a six-year-old girl named Sally has been trapped under a fallen tree 30 yards north of the falls on Coldwater Creek near the old mine shaft and oh, by the way, she’s diabetic too, so bring some insulin.”

Carbon Dating

In 1969, archaeologist James Whittall unearthed stone tools at the site, along with charcoal flakes that could be carbon dated. The dating showed the tools’ user was working around 1,000 B.C., according to Goudsward and Stone.

Whittall recovered charcoal from several other locations on-site and carbon dating ranged from 2,000 B.C. to 400 B.C.

Dating Using Astronomical Alignments

Astrological alignments concur. Astronomer Dr. Louis Winkler, the principal site scientist, found the positions of some stones align with where the stars and other celestial objects would have been about 2,000 years ago. He has also done radiocarbon and laser theodolite dating to support a Bronze Age origin (2,000 B.C.–1,500 B.C.).

Anthropologist Bob Goodby of the New Hampshire Archaeological Society (NHAS) said the alignments are “coincidental.”

“With so much stone around, it wouldn’t be that difficult to find some alignments that correspond to celestial things,” Goodby told Boston University publication the Bridge. This isn’t the only “coincidence” cited by critics of the ancient-European-origin theory, nor the only one cited as a little too “coincidental” by supporters of the theory.

For example, critic Richard Boisvert, New Hampshire’s deputy state archaeologist, admitted the structures resemble ancient European megalithic structures, but that it’s a coincidence. He told Discovery that it’s a case of the same form-fitting the same function.

Professor of astronomy at New Hampshire Technical Institute Alan Hill does not see the astronomical alignments as coincidence. He told New York Times that the megaliths mark cross-quarter days, the halfway points between the solstices and equinoxes. Celts are the only ones to celebrate cross-quarter holidays, he said. Hill dismissed the theory that the structures are cellars built in the past few centuries, partly because the doors are not wide enough to admit wheelbarrows. A local lawyer and mystery novelist, David Brody, told the Times there are too many similarly puzzling stones and structures in the region to write it all off as coincidence.

Stone-on-Stone Tools Suggest Primitive Builders

The builders apparently used stone tools, not metal tools. Boisvert’s boss, New Hampshire state archaeologist Gary Hume, told Discovery the stone-on-stone workmanship is similar to that of Native Americans. He was hesitant to say the megaliths could be 4,000 years old, but he seemed to leave the possibility open. He said he wasn’t going to question “the two reputable surveyors who had vouched for the alignments,” wrote Wright.

The Natives and the Celts are not the only groups archaeologists have pinned as the potential builders. Some say it may have been the Phoenicians, the people of an ancient kingdom on the Mediterranean. The standing stones align with the location of the polestar Thuban during Phoenician times, according to Wright.

Jonathan Pattee, a shoemaker and his family lived on the site throughout much of the 19th century, and many say he and his family built the structures. Dennis Stone, Robert Stone’s son who is also currently owner and operator of the site, told Discovery that some of the structures were probably built by Pattee, but certainly not all. Others have also said the intricacies of construction and alignment were not likely carried out by the Pattee family, and the family would have used metal tools, not stone tools.

Goodby and other critics of the ancient-origin theory say archaeologists would have found signs of people living on or near the site, such as burial grounds. He said the sacrificial stone was probably actually a place for inhabitants in more recent history to make soap. Whatever the theories, as Goudsward and Stone write: “There has been so much damage in the last four millennia that no matter who you believe built the site, there is just enough physical evidence to warrant further investigation along that line. This has produced a spectrum of theories as wide and expansive as the skies that may or may not be charted by the ancient monoliths.”