World-first Temple? Ancient site older than Gobeklitepe may have been unearthed in turkey

According to a Turkish university rector, new archeological excavations have uncovered an old site older than Gobeklitepe, regarded as the oldest temple in the world.

The Anadolu Agency’s Ibrahim Ozcosar, the rector of Mardin Artuklu University, said the Boncuklu Tarla (Beaded Field) discoveries in Gobeklitepe, a prominent archeological site in the southeastern Sanliurfa region of Turkey and even 1,000 years older.

Work on archaeological digs began in 2012 in the neolithic Boncuklu Tarla district in Dargecit.

Throughout the years Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Hittites, Assyrians, Romans, Seljuks, and Ottomans have been known to have been home to the city.

“It is possible to consider this as a finding that proves the first settlers [in the area] were believers,” Ozcosar said.

“This area is important in terms of being one of the first settled areas of humanity and shows that the first people settling here were believers,” he added, pointing to the similar discoveries in Gobeklitepe and Boncuklu Tarla.

Ergul Kodas, an archaeologist at Artuklu University and advisor to the excavation area, told Anadolu Agency that the history of the Boncuklu Tarla is estimated to be around 12,000-years old.

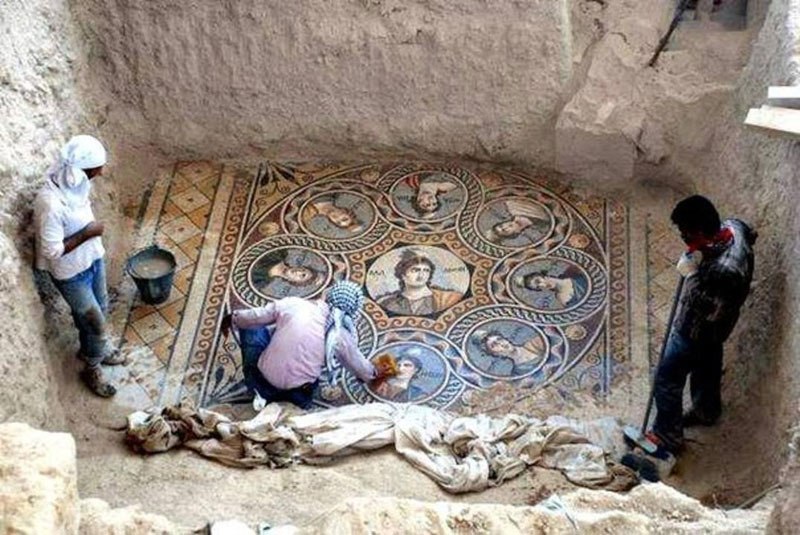

“Several special structures which we can call temples and special buildings were unearthed in the settlement, in addition to many houses and dwellings,” Kodas said.

“This is a new key point to inform us on many topics such as how the [people] in northern Mesopotamia and the upper Tigris began to settle, how the transition from hunter-gatherer life to food production happened and how cultural and religious structures changed,” he added.

According to Kodas, there are buildings in the area similar to those in Gobeklitepe. Boncuklu Tarla is almost 300 kilometers east of Gobeklitepe.

“We have identified examples of buildings which we call public area, temples, religious places in Boncuklu Tarla that are older compared to discoveries in Gobeklitepe,” he added.

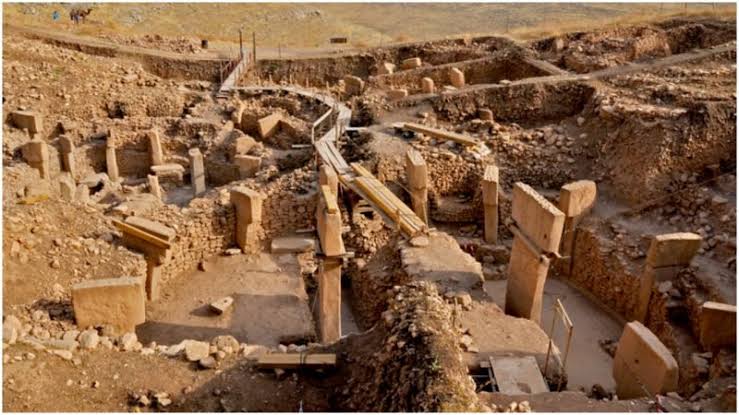

Gobeklitepe, declared an official UNESCO World Heritage Site last year, was discovered in 1963 by researchers from the universities of Istanbul and Chicago.

The German Archaeological Institute and Sanliurfa Museum have been carrying out joint excavations at the site since 1995.

They found T-shaped obelisks from the Neolithic era towering 10-20 feet (3-6 meters) high and weighing 40-60 tons.

During excavations, various historical artifacts, including a 26-inch (65-centimeter) long human statue dating back 12,000 years, have also been discovered.