Humans May Have Smoked Tobacco 12,300 Years Ago, Scientists Find New Evidence in Utah

Humankind’s addiction to tobacco runs deep: Archaeologists in Utah have discovered what appears to be the earliest known use of wild tobacco, stretching back 12,500 years—some 9,000 years earlier than the previously dated evidence.

A team from the Far Western Anthropological Research Group in Henderson, Nevada, and the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in Cortez, Colorado, found Nicotiana attenuata, or coyote tobacco, seeds around a manmade hearth or firepit at the Wishbone site in Utah’s Great Salt Lake Desert, not far from Salt Lake City.

The researchers published their findings in the journal Nature Human Behavior.

Wishbone got its name from the large number of waterfowl bones found at the site, where ducks were likely the mainstay of the prehistoric human diet. But tobacco wouldn’t have grown in what was then a marshy area, with its closest natural habitat some eight miles away.

“It was a completely-out-of-nowhere find. It’s very uncommon to find tobacco seeds, even at later sites: they are really small and they are not food, so they don’t occur very often,” Far Western’s Daron Duke, the paper’s lead author, told Haaretz. “Theoretically, it is possible a duck could nibble on a tobacco plant, but that duck would have to avoid hundreds of square kilometres of its typical diet, go up a rocky mountain range, which they don’t do, and eat a fairly uncommon plant.”

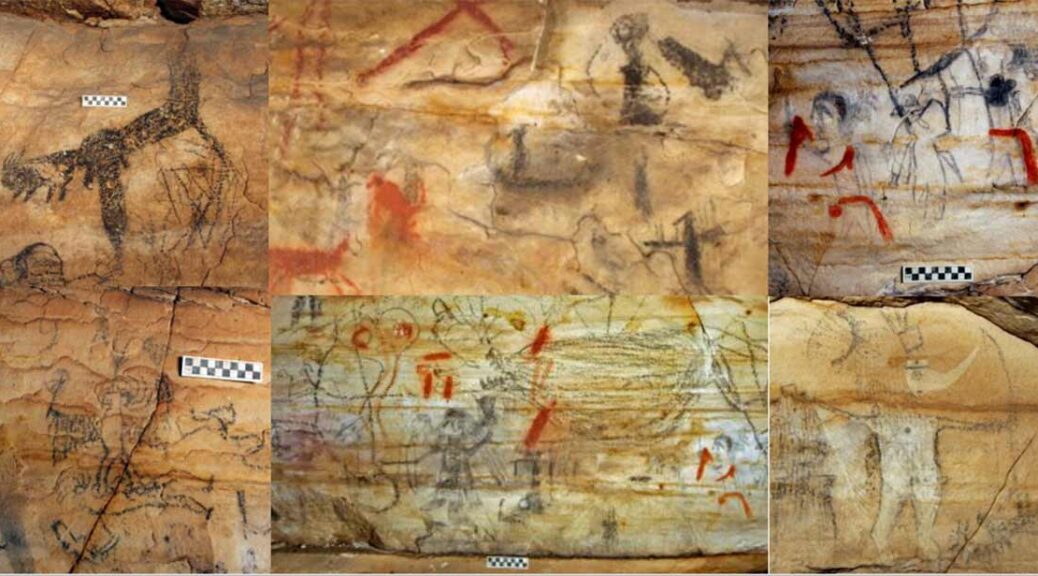

Also in the ashes were seeds from other plants that ancient humans are known to have consumed, suggesting that people intentionally brought tobacco seeds to the site—the population at Wishbone appears to have travelled widely each year.

The seeds wouldn’t have burned well, so they were probably not being used to feed the fire. Most likely, the ancients liked to chew tobacco, releasing the addictive nicotine for a dopamine high.

“To see them, fireside, using tobacco—we can pretty readily imagine what they were getting out of it,” Duke told Scientific American. “It’s very human to imbibe.”

Duke has been conducting research at Wishbone, in the Utah Test and Training Range, for 20 years, and found the remnants of the ancient hearth—just a “little black smudge on the open mudflats of the Great Salt Lake Desert,” he told CNN—back in 2015.

The site has also yielded Haskett-style spear tips made from obsidian, a kind of volcanic glass, that would have been used to hunt large game.

Wishbone has a “unique potential to tell us about how people lived,” Duke told Inverse. “It truly is a fascinating place to work, as one of the most barren settings you can find in the United States.”

To figure out what materials had been left behind in the ashes, scientists used a technique called manual flotation, submerging the sediment samples in water and separating organic and non-organic material.

Radiocarbon dating showed the fire burned approximately 12,300 years ago, with four wild tobacco seeds identified amid the charred remains.

Before the team’s discovery, the earliest documented use of tobacco was in smoking pipes used in the Alabama region some 3,300 years ago, which was dated in 2018.

The new evidence suggests that tobacco use was already firmly entrenched in Native American cultures by that point in time.

“People in the past were the ultimate botanists and identified the intoxicant values of tobacco quickly upon arriving in the Americas,” Duke told Live Science.

The long-held Clovis theory suggests people began travelling over the land bridge that connected Siberia and Alaska some 13,500 to 13,000 years ago. But some recent archaeological discoveries—including the continent’s oldest human footprints—suggest that pre-Clovis people had a presence in North America during the Ice Age, perhaps up to 20,000 or 30,000 years ago.

“On a global scale, tobacco is the king of intoxicant plants, and now we can directly trace its cultural roots to the Ice Age,” Duke told Reuters.