What Powered The Vimanas? India’s 6,000-Year-Old Flying Machines

According to Ancient Indian history – one of the most extensive on the planet – their ancient sacred texts called the ‘Vedas’ speak of incredible flying ships that visited our planet over 6000 years ago. Throughout history, many common myths and legends mention incredible flying machines and how ancient people traveled great distances through the air: the flying carpets of ancient Arabia, Ezekiel’s wheel, Solomons’ ability to travel from one place to another and the magical chariots or ‘vimana’ mentioned in ancient Indian and Chinese texts.

According to Ancient Indian history –one of the most extensive on the planet– their ancient sacred texts called the ‘Vedas’ speak of amazing flying ships that visited our planet over 6000 years ago. While there are many who oppose the existence of the Vimana, millions of people around the world are concerned that thousands of years ago, ancient mankind was visited by incredible flying machines, piloted by the ‘gods’.

With the help of the Vimana, ancient astronauts visited different places on our planet with ease, spreading knowledge and wealth among ancient, primitive civilizations. Reference to the ancient Vimana can be found in the Mahabharata, which is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India:

“At Rama`s behest, the magnificent chariot rose up to a mountain of cloud with a tremendous din. Another passage reads: Bhima flew with his Vimana on an enormous ray which was as brilliant as the sun and made a noise like the thunder of a storm. In the ancient Vymanka-Shastra (the science of aeronautics), there is a description of a Vimana: “An apparatus which can go by its own force, from one place to place or globe to the globe”.

Dr. Raghavan points out, “The text’s revelations become even more astounding. Thirty-one parts of which the machine consists are described, including a photographing mirror underneath.

“The text also enumerates 16 kinds of metal that are needed to construct the flying vehicle: `Metals suitable, lighare 16 kinds`. But only three of them are known to us today. The rest remain untranslatable.”

Another authority who agrees with Dr. Raghavan`s interpretations is Dr. A.V. Krishna Murty, professor of aeronautics at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore.

“It is true,” Dr. Krishna Murty says, “that the ancient Indian Vedas and other text refer to aeronautics, spaceships, flying machines, ancient astronauts. A study of the Sanskrit texts has convinced me that ancient India did know the secret of building flying machines and that those machines were patterned after spaceships coming from other planets.”

However, What Fueled this Ancient Vimana?

The Vaimānika Śāstra, an early 20th-century Sanskrit text on aerospace technology, makes a claim that the vimānas mentioned in ancient Sanskrit epics were advanced aerodynamic flying vehicles, similar to a rocket capable of interplanetary flight as backed up by the ancient alien theory. Revealed in 1952 by G. R. Josye, the texts contain 3000 shlokas in 8 chapters which Shastry claimed were psychically delivered to him by the ancient Hindu sage Bharadvaja. The propulsion of the Vimanas According to Kanjilal (1985) is by a “Mercury Vortex Engines”, a concept similar to electric propulsion. However, many people argue that a far greater, more accessible and ‘free’ power source was available to the ancient Vimana craft. It is noteworthy to mention that a couple of years ago, Chinese researchers discovered ancient Sanskrit documents in Lhasa, Tibet, dating back thousands of years. The ancient texts were sent to the University of Chandigarh for translation. The results were shocking. According to Dr. Ruth Reyna the translated texts, allegedly are ‘blueprints’ for the construction of interstellar spaceships.

According to the translated documents, the propulsion system designed for the spaceships was based on antigravitational technology, and based on a system analogous to that of “laghima,” the unknown power of the ego that exists in man’s physiological makeup, “a centrifugal force strong enough to counteract all gravitational pull.”

Interestingly, according to Hindu Yogis, the mysterious “laghima” force is what enables people to levitate.

Dr. Reyna explained that “on board, these machines which were called ‘Astras,’ the builders of the crafts could have sent a detachment of men to any planet. The manuscripts, however, do not mention how interplanetary communication was achieved, but they do mention a trip from the Earth to the Moon, though it is unclear whether the trip was just planned or actually carried out.”

However, one of the great Indian epics, the Ramayana, does have a highly detailed story in it of a trip to the moon in a Vimana (or “Astra”), and in fact details a battle on the moon with an “Asvin” (or Atlantean” airship.

Indian scientists were extremely reserved about the value of these documents but became less so when the Chinese announced that certain parts of the information were being studied for inclusion in their space program.

But can we actually ‘reverse engineer’ ANCIENT technology? Well… depends on what you think is possible. Interestingly in the Sanskrit Samarangana Sutradhara, it is written:

“Strong and durable must the body of the Vimana be made, like a great flying bird of light material. Inside one must put the mercury engine with its iron heating apparatus underneath. By means of the power latent in the mercury which sets the driving whirlwind in motion, a man sitting inside may travel a great distance in the sky. The movements of the Vimana are such that it can vertically ascend, vertically descend, and move slanting forwards and backwards. With the help of the machines, human beings can fly in the air, and heavenly beings can come down to earth.”

Interestingly, in the Law of the Babylonians, the Hakatha unambiguously states:

“The privilege of operating a flying machine is great. The knowledge of flight is among the most ancient of our inheritances. A gift from ’those from upon high’. We received it from them as a means of saving many lives.”

“The Pushpaka Vimana was a gigantic ‘plane’ the size of a large city entirely capable of holding unlimited numbers of people…”

“…Three flying cities were made for and were used by the Demons… One was in a stationary orbit in the sky, another moving in the sky and one was permanently stationed on the ground. These were docked like modern spaceships in the sky… and at a fixed latitude/longitude.

“Siva’s arrow obviously referred to a blazing missile fired from a satellite specially built for the purpose…Vestiges of onetime prosperous civilization destroyed in battles flicker through these legends…” – Prof. D.K. Kanjilal’s observations of the Matsyapurana

Harnessing Earth’s Natural Energy

But is it possible that the ancient Vimana’s were built so they could access the planet’s natural energy? What if thousands of years ago, ancient flying machines used Earth’s natural energy to charge and reload? Is it possible that ancient monuments like pyramids were, in fact, giant energy transmitters that fueled the ancient Vimana?

Interestingly Stone like metal can be charged and is able to carry out electrical charges. What if ancient sites on Earth were specifically placed on so-called magnetic vortexes or electrical ‘Ley Lines’?

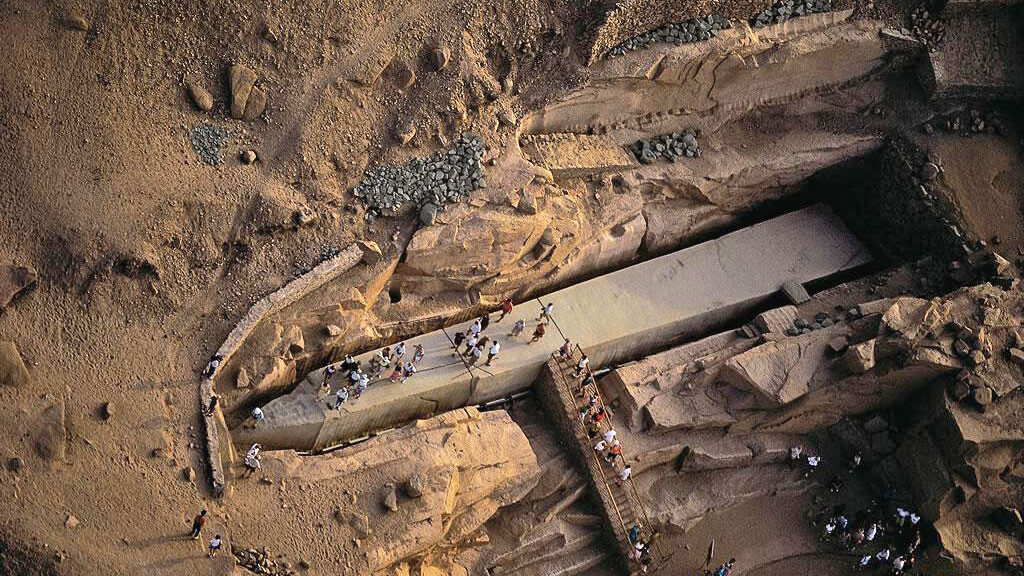

What if there is a far greater meaning to the countless number of ancient Indian Pyramids, monoliths, megalithic statues, steles, obelisks and totems, and what if all of these structures, not only from ancient India but different civilizations around the world, had a special scientific purpose: to transmit vast amounts of energy. Many researchers argue that intricate ancient stonework attributed to the Incas, Egyptians, East Indians, Maya and other ancient civilizations has a specific purpose, and was not only aesthetic in nature. It is noteworthy to mention that many consider the Great Pyramid of Giza as one of the best examples of ancient energy machines. It was a Tesla-like power plant created thousands of years ago. It was a huge ancient structure that was capable of using the Earth’s natural properties in order to create or produce a great amount of energy. This energy is believed to have been used by the ancient Egyptians and other cultures such as the ancient Maya and other cultures around the globe for millennia. This theory, however, has been firmly rejected by mainstream researchers. If we approach the history of ancient civilizations from another perspective, we will encounter that ancient civilizations around the globe were, in fact, extremely sophisticated and used advanced technologies thousands of years before mainstream science ‘reinvented them’.

These advanced technologies were present in ancient Egypt, Ancient Sumer, and in North, Central and South America. Electricity, electrochemistry, electromagnetic technology, metallurgy, advanced engineering, including hydrogeology, chemistry, physics and advanced forms of mathematics and astronomy were all used thousands of years ago to great extents.