DNA from child burials reveals ‘profoundly different’ human landscape in ancient Africa

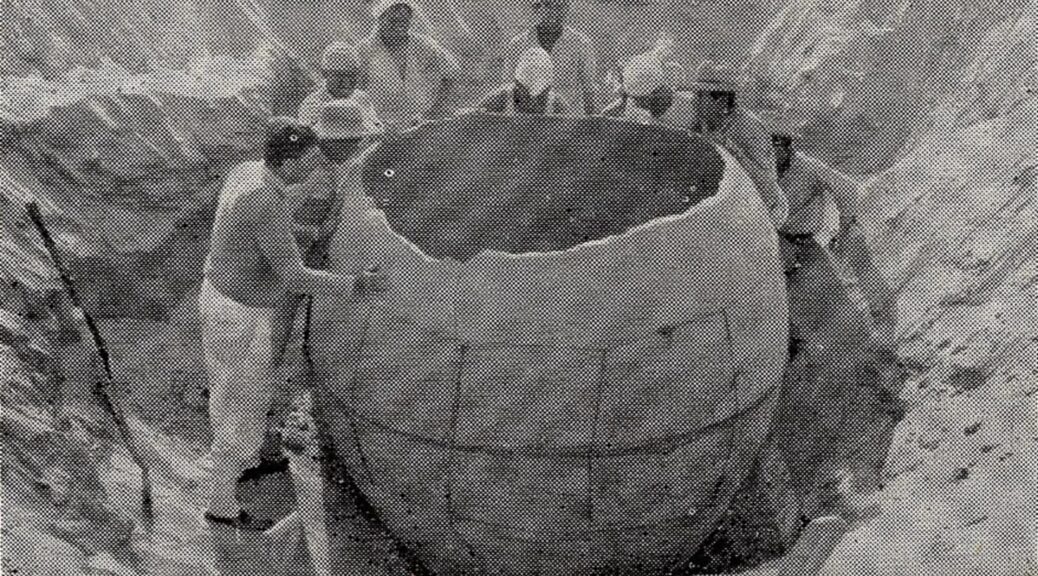

Central Africa is too hot and humid for ancient DNA to survive—or so researchers thought. But now the bones of four children buried thousands of years ago in a rock shelter in the grasslands of Cameroon have yielded enough DNA for scientists to analyze.

It’s the first ancient DNA from humans in the region, and as the team reports today in Nature, it holds multiple surprises. For one, the area today is the homeland of Bantu speakers, the majority group in western and Central Africa.

But the children turned out to be most closely related to hunter-gatherers such as the Baka and Aka—groups traditionally known as “pygmies”—who today live at least 500 kilometres away in the rainforests of western Central Africa.

“In the supposed cradle of Bantu languages and, therefore, Bantu people, these people are basically ‘pygmy’ hunter-gatherers,” says Lluís Quintana-Murci, a population geneticist at the Pasteur Institute and CNRS, the French national research agency, who was not part of the new study.

He and others have long suspected that these groups had a larger range before the Bantu population exploded 3000 years ago.

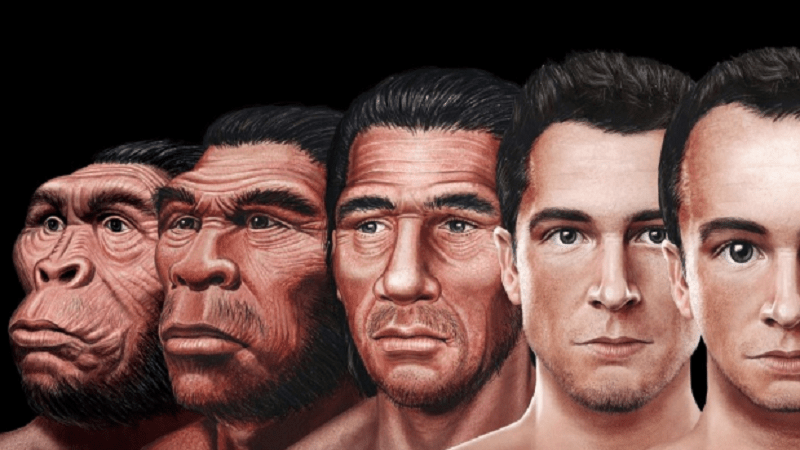

The second big surprise came when the team compared the children’s DNA to other genetic data from Africa and found hints that the Baka, Aka, and other Central African hunter-gatherers belong to one of the most ancient lineages of modern humans, with roots going back 250,000 years.

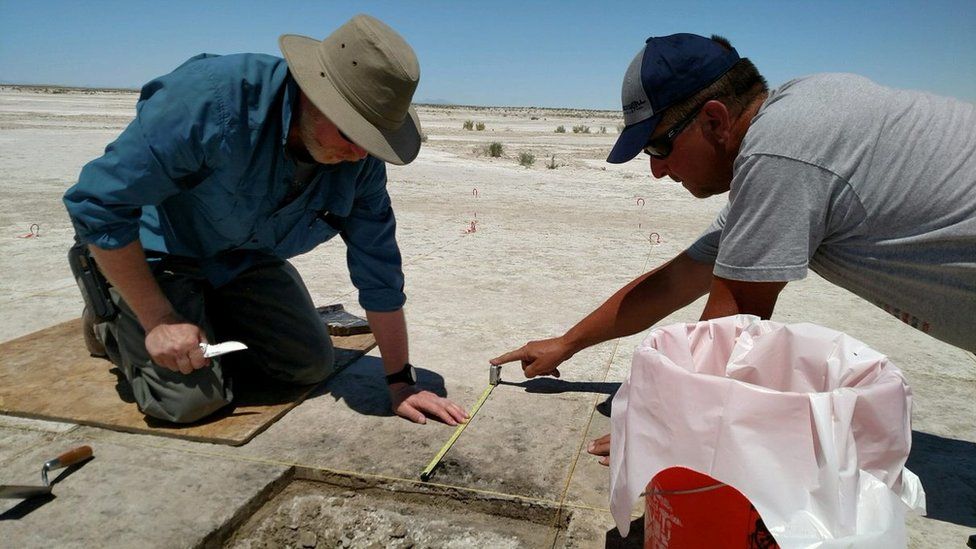

In the new study, geneticists and archaeologists took samples from the DNA-rich inner ear bones of the four children, who were buried 3000 and 8000 years ago at the famous archaeological site of Shum Laka.

The researchers were able to sequence high-quality full genomes from two of the children and partial genomes from the other two.

Comparing the sequences to those of living Africans, they found that the four children were distant cousins and that all had inherited about one-third of their DNA from ancestors most closely related to the hunter-gatherers of western Central Africa.

Another two-thirds of children’s DNA came from an ancient “basal” source in West Africa, including some from a “long lost ghost population of modern humans that we didn’t know about before,” says population geneticist David Reich of Harvard University, leader of the study.

The discovery underscores the diversity of African groups that inhabited the continent before the Bantus began to herd livestock in the grassy highlands of western Central Africa.

The Bantus made pottery and forged iron, and their burgeoning populations rapidly displaced hunter-gatherers across Africa. Analyzing DNA from a time before this expansion offers “a glimpse of a human landscape that is profoundly different than today,” Reich says.

The team compared the children’s DNA to ancient DNA extracted earlier from a 4500-year-old individual from Mota Cave in Ethiopia and sequences from other ancient and living Africans, using various statistical methods to sort out how they all were related, which groups came first, and when they split from one another.

The team’s bold new model pushes back Central African hunter-gatherer origins to 200,000 to 250,000 years ago—not long after our species evolved.

The model suggests their lineage split from three other modern human lineages: one leading to the Khoisan hunter-gatherers in southern Africa, one to East Africans, and one to a now-extinct “ghost” population.

Early diversification of modern humans fits the great variation seen in fossils of early Homo sapiens, says paleoanthropologist Katerina Harvati of the University of Tübingen, who is not part of this study.

The lineages would have parted company and moved off into different parts of Africa 200,000 to 250,000 years ago, preserving their distinctness by only occasionally interbreeding at the boundaries.

But others say that although the new study offers compelling new evidence, the data aren’t yet solid enough to build a reliable model.

“It needs to be further tested with additional whole-genome data from both modern and, if possible, ancient DNA from more Africans,” says evolutionary geneticist Sarah Tishkoff of the University of Pennsylvania.

That may be possible. A third key lesson from the study is that ancient DNA can be extracted from bones in Central Africa after all. “The future is not as bleak for ancient DNA in these regions,” says population geneticist Joshua Akey of Princeton University.