Maya Farmers May Have Planned for Population Growth

For years, experts in climate science and ecology have held up the agricultural practices of the ancient Maya as prime examples of what not to do.

“There’s a narrative that depicts the Maya as people who engaged in unchecked agricultural development,” said Andrew Scherer, an associate professor of anthropology at Brown University. “The narrative goes: The population grew too large, the agriculture scaled up, and then everything fell apart.”

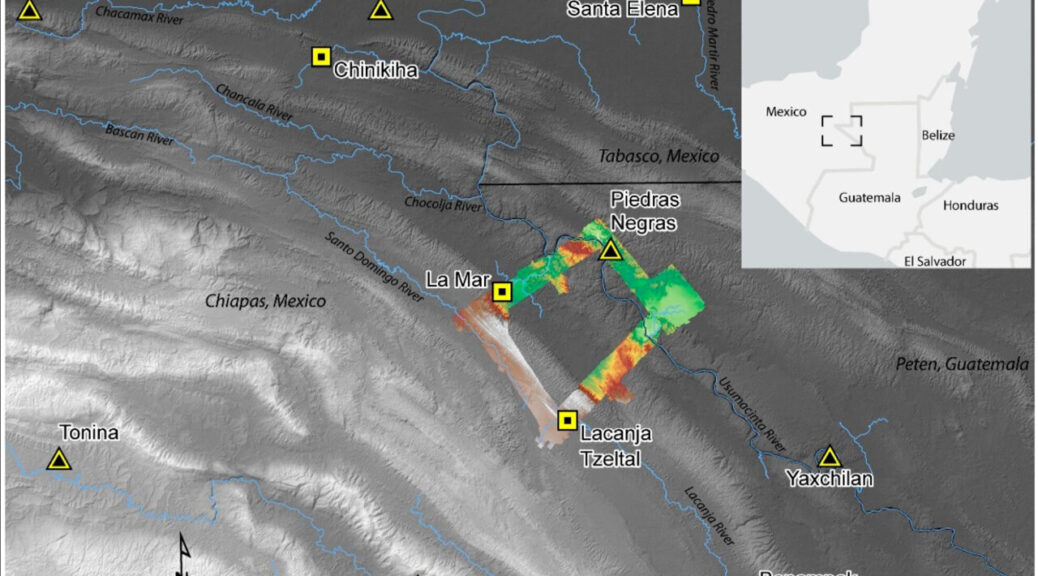

But a new study, authored by Scherer, students at Brown and scholars at other institutions, suggests that that narrative doesn’t tell the full story. Using drones and lidar, a remote sensing technology, a team led by Scherer and Charles Golden of Brandeis University surveyed a small area in the Western Maya Lowlands situated at today’s border between Mexico and Guatemala.

Scherer’s lidar survey — and, later, boots-on-the-ground surveying — revealed extensive systems of sophisticated irrigation and terracing in and outside the region’s towns, but no huge population booms to match.

The findings demonstrate that between 350 and 900 A.D., some Maya kingdoms were living comfortably, with sustainable agricultural systems and no demonstrated food insecurity. “It’s exciting to talk about the really large populations that the Maya maintained in some places; to survive for so long with such density was a testament to their technological accomplishments,” Scherer said.

“But it’s important to understand that that narrative doesn’t translate across the whole of the Maya region. People weren’t always living cheek to jowl. Some areas that had the potential for agricultural development were never even occupied.”

The research group’s findings were published in the journal Remote Sensing. When Scherer’s team embarked on the lidar survey, they weren’t necessarily attempting to debunk long-held assumptions about Maya agricultural practices. Rather, their primary motivation was to learn more about the infrastructure of a relatively understudied region.

While some parts of the western Maya area are well studied, such as the well-known site of Palenque, others are less understood, owing to the dense tropical canopy that has long hidden ancient communities from view. It wasn’t until 2019, in fact, that Scherer and colleagues uncovered the kingdom of Sak T’zi’, which archaeologists had been trying to find for decades.

The team chose to survey a rectangle of land connecting three Maya kingdoms: Piedras Negras, La Mar and Sak Tz’i’, whose political capital was centred on the archaeological site of Lacanjá Tzeltal. Despite being roughly 15 miles away from one another as the crow flies, these three urban centres had very different population sizes and governing power, Scherer said.

“Today, the world has hundreds of different nation-states, but they’re not really each other’s equals in terms of the leverage they have in the geopolitical landscape,” Scherer said. “This is what we see in the Maya empire as well.”

Scherer explained that all three kingdoms were governed by an ajaw, or a lord — positioning them as equals, in theory. But Piedras Negras, the largest kingdom, was led by a k’uhul ajaw, a “holy lord,” a special honorific not claimed by the lords of La Mar and Sak Tz’i’. La Mar and Sak Tz’i’ weren’t exactly equal peers, either: While La Mar was much more populous than the Sak T’zi’ capital Lacanjá Tzeltal, the latter was more independent, often switching alliances and never appearing to be subordinate to other kingdoms, suggesting it had greater political autonomy.

The lidar survey showed that, despite their differences, these three kingdoms boasted one major similarity: agriculture that yielded a food surplus.

“What we found in the lidar survey points to strategic thinking on the Maya’s part in this area,” Scherer said.

“We saw evidence of long-term agricultural infrastructure in an area with relatively low population density — suggesting that they didn’t create some crop fields late in the game as a last-ditch attempt to increase yields, but rather that they thought a few steps ahead.”

In all three kingdoms, the lidar revealed signs of what the researchers call “agricultural intensification” — the modification of land to increase the volume and predictability of crop yields. Agricultural intensification methods in these Maya kingdoms, where the primary crop was maize, included building terraces and creating water management systems with dams and channelled fields. Penetrating through the often-dense jungle, the lidar showed evidence of extensive terracing and expansive irrigation channels across the region, suggesting that these kingdoms were not only prepared for population growth but also likely saw food surpluses every year.

“It suggests that by the Late Classic Period, around 600 to 800 A.D., the area’s farmers were producing more food than they were consuming,” Scherer said. “It’s likely that much of the surplus food was sold at urban marketplaces, both as producer and as part of prepared foods like tamales and gruel, and used to pay tribute, a tax of sorts, to local lords.”

Scherer said he hopes the study provides scholars with a more nuanced view of the ancient Maya — and perhaps even offers inspiration for members of the modern-day agricultural sector who are looking for sustainable ways to grow food for an ever-growing global population. Today, he said, significant parts of the region are being cleared for cattle ranching and palm oil plantations. But in areas where people still raise corn and other crops, they report that they have three harvests a year — and it’s likely that those high yields may be due in part to the channelling and other modifications that the ancient Maya made to the landscape.

“In conversations about contemporary climate or ecological crises, the Maya are often brought up as a cautionary tale: ‘They screwed up; we don’t want to repeat their mistakes,’” Scherer said. “But maybe the Maya were more forward-thinking than we give them credit for. Our survey shows there’s a good argument to be made that their agricultural practices were very much sustainable.”

Aside from Scherer and Golden, study authors include Brown PhD students Mark Agostini, Morgan Clark, Joshua Schnell and Bethany Whitlock; recent Brown PhD graduates Mallory Matsumoto, now an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin, and Alejandra Roche Recinos, now a visiting assistant professor at Reed College; and researchers from McMaster University and the University of Florida. The research was funded in part by the Alphawood Foundation, the National Science Foundation and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.