17th-Century Coin Hoard Uncovered in Poland

A metal detectorist searching for discarded tractor parts on a Polish farm discovered a completely different type of valuable metal: A spectacular hoard of 17th-century coins buried beneath the soil.

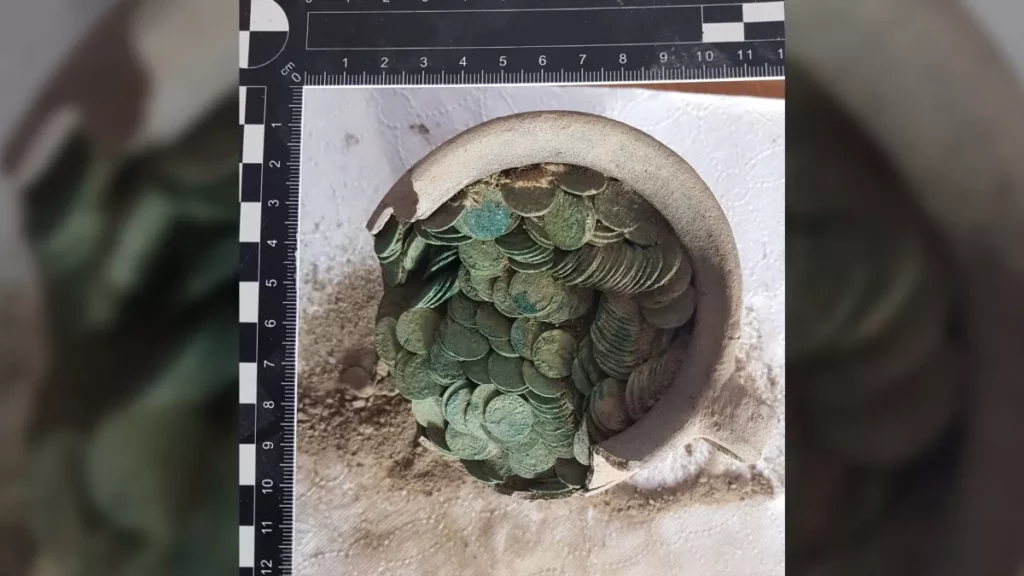

The hoard — a vast stash of about 1,000 copper coins — was found in late February near the small village of Zaniówka in eastern Poland, near the borders with Belarus and Ukraine, by a local man, Michał Łotys.

Łotys was using a new metal detector to find spare parts for his sister’s tractor; and so when the instrument started beeping in one of the farm’s fields, he scraped away a layer of the topsoil. That revealed the coins spilling out of a broken clay “siwak” — a jug in a local style with one handle and a narrow neck.

Using a metal detector to search for buried relics without a permit is illegal in Poland, and so Łotys contacted archaeologists in the nearby city of Lublin, about 95 miles (150 kilometers) southeast of Warsaw, who visited the farm the next day.

Their investigations showed that the location of the hidden hoard was clearly outlined on the surface of the soil, which indicated it had been buried there intentionally, according to a report in the Polish news outlet The First News.

Buried hoard

Dariusz Kopciowski, the director of Lublin’s heritage conservation agency, announced in a Facebook post on March 2 that the hoard has about 1,000 Polish and Lithuanian copper coins minted in the 17th century.

Oxidation after roughly 400 years in the ground means all the copper coins are now colored green; and many have corroded together in layers. But about 115 of the coins are loose, and the entire hoard weighs about 6.6 pounds (3 kilograms), Kopciowski noted.

Investigations show most of the coins were created between 1663 and 1666 in mints in Warsaw; Vilnius in Lithuania; and Brest, which is now in Belarus but was then part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

According to the Polish metal detectorist website Zwiadowca Historii, such coins are known as “boratynki” after Tito Livio Burattini, who was the manager of the Kraków mint at that time.

Burattini, an Italian, was a famed inventor and polymath who introduced copper coins to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth because they were much cheaper to make than the existing silver coins of the realm; and because its treasury was devastated after years of war with Sweden, Russia and Cossacks.

The “boratynki” coins were initially popular, although Burattini was later accused of debasing the copper metal they were made of and reaping huge profits.

For a start, they weren’t very valuable, which meant they could be used in everyday transactions; the entire hoard of 1,000 copper coins from Zaniówka would buy only “about two pairs of shoes” at the time, although they’re worth more now as historical relics, Zwiadowca Historii reported.

The Zaniówka coin hoard will now be transferred to specialists at a museum in the nearby city of Biała Podlaska for further investigations, Kopciowski said.

Fragments of the broken clay jug and several pieces of fabric from the time were also found at the site, he said in the statement.