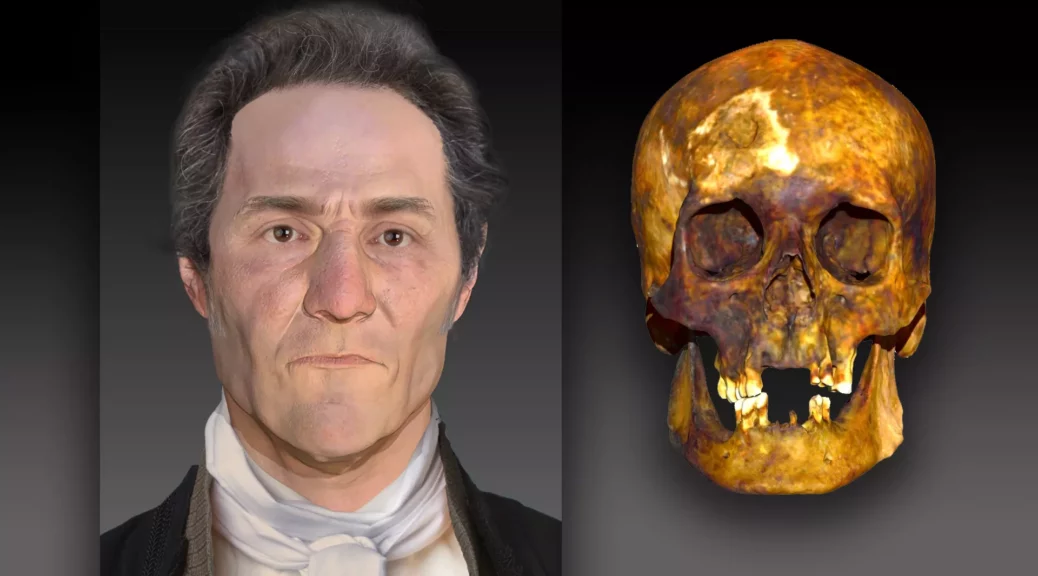

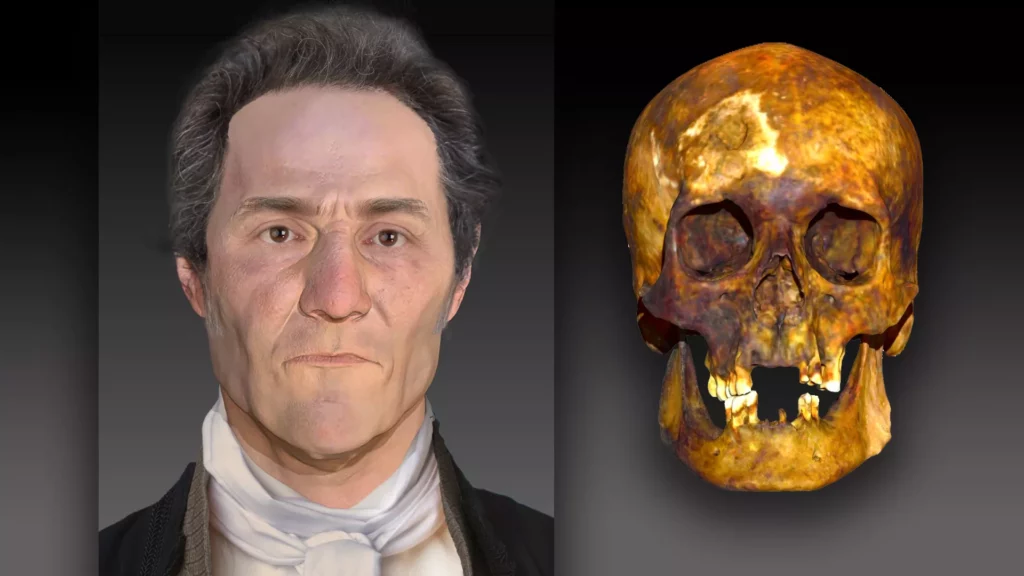

See the face of an 18th century ‘vampire’ buried in Connecticut

In the late 18th century, a man was buried in Griswold, Connecticut, with his femur bones arranged in a criss-cross manner — a placement indicating that locals thought he was a vampire. However, little else was known about him.

More than 200 years later, DNA evidence is revealing what he may have looked like. (And yes, he was genetically human.)

After performing DNA analyses, forensic scientists from a Virginia-based DNA technology company named Parabon NanoLabs, and the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory (AFDIL), a branch of the U.S. Armed Forces Medical Examiner System based in Delaware, concluded that at the time of death, the deceased male (known as JB55) was about 55 years old and suffered from tuberculosis.

Using 3D facial reconstruction software, a forensic artist determined that JB55 likely had fair skin, brown or hazel eyes, brown or black hair and some freckles, according to a statement.

Based on the positioning of the legs and skull in the grave, researchers suspect that at some point the body was disinterred and reburied, a practice often associated with the belief that someone was a vampire. Historically, some people once thought that those who died of tuberculosis were actually vampires, according to the statement.

“The remains were found with the femur bones removed and crossed over the chest,” Ellen Greytak, director of bioinformatics at Parabon NanoLabs and the technical lead for the organization’s Snapshot Advanced DNA Analysis division, told Live Science. “This way they wouldn’t be able to walk around and attack the living.”

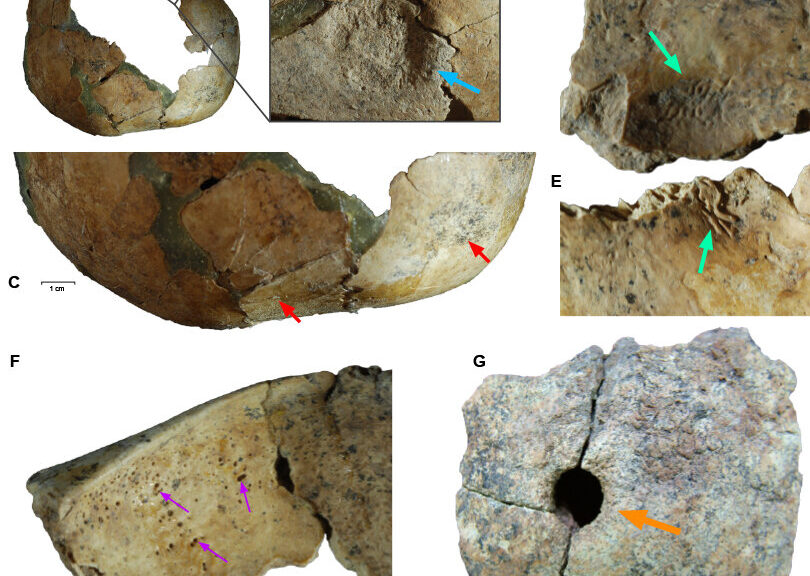

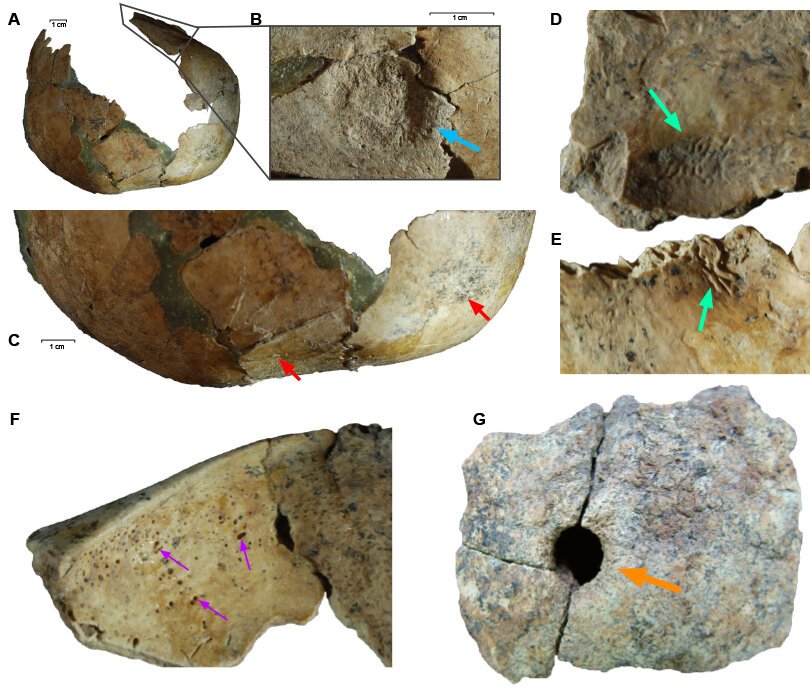

To perform the analyses, forensic scientists began by extracting DNA from the man’s skeletal remains. However, working with bones that were more than two centuries old proved challenging.

“The technology doesn’t work well with bones, especially if those bones are historical,” Greytak said. “When bones become old, they break down and fragment over time. Also, when remains have been sitting in the environment for hundreds of years, the DNA from the environment from things like bacteria and fungi also end up in the sample. We wanted to show that we could still extract DNA from difficult historical samples.”

In traditional genome sequencing, researchers strive to sequence each piece of the human genome 30 times, which is known as “30X coverage.” In the case of the decomposed remains of JB55, the sequencing only yielded about 2.5X coverage.

To supplement this, researchers extracted DNA from an individual buried nearby who was believed to be a relative of JB55. Those samples yielded even poorer coverage: approximately 0.68X.

“We did determine that they were third-degree relatives or first cousins,” Greytak said.

Archaeologists originally unearthed the supposed vampire’s remains in 1990.

In 2019, forensic scientists extracted his DNA and ran it through an online genealogical database, determining that JB55 was actually a man named John Barber, a poor farmer who likely died of tuberculosis.

The nickname JB55 was based on the epitaph spelled out on his coffin in brass tacks, denoting his initials and age at death.

This week, researchers will unveil their new findings, including facial reconstruction, at the International Symposium on Human Identification (ISHI) conference, held from Oct. 31 to Nov. 3 in Washington, D.C.