Ship’s Cargo Offers Clues to Medieval Trade Routes

Research at the University of Gothenburg has shown that the Skaftö wreck had probably taken on cargo in Gdańsk in Poland and was heading towards Belgium when it foundered in the Lysekil archipelago around 1440.

Modern methods of analysis of the cargo are now providing completely new answers about the way trade was conducted in the Middle Ages.

“The analyses we have carried out give us a very detailed picture of the ship’s last journey and also tell us about the geographical origins of its cargo. Much of this is completely new knowledge for us,” says Staffan von Arbin, a maritime archaeologist.

For example, it was not previously known that calcium oxide (CaO), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, was exported from Gotland in the 15th century.

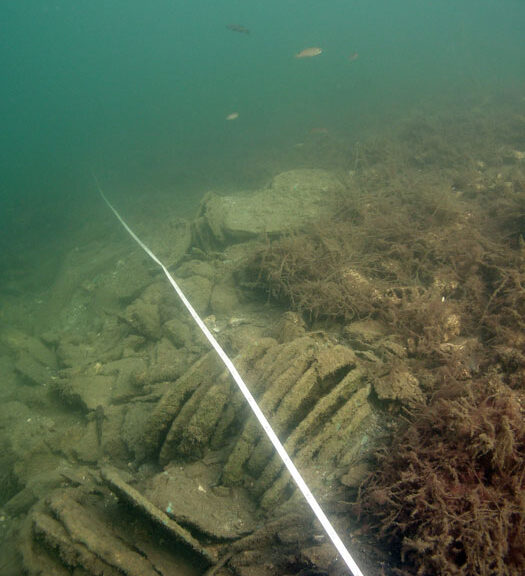

In 2003, the Skaftö wreck was found at the bottom of the sea off Lysekil, north of Gothenburg. But it is only now that researchers have been able to carry out analyses of its cargo using new, modern methods.

An international research team, headed by maritime archaeologist Staffan von Arbin at the University of Gothenburg, has succeeded in mapping the origins of its cargo and the probable route of the ship. The study contributes new knowledge about the goods traded in the Middle Ages and the trade routes in that period.

The cargo included copper, oak timber, quicklime, tar, bricks and roof tiles. Samples of the cargo have been taken up from the wreck during previous underwater archaeological investigations carried out by the Bohusläns museum. But it’s only now that analyses of its cargo have been possible using modern analysis methods.

From Gotland in Sweden

With these analyses, the researchers have been able to establish that the copper was mined in two areas in what is currently Slovakia, for example. The analyses also show that the bricks, timber and probably also the tar originated in Poland, while the quicklime is apparently from Gotland.

According to medieval sources, copper was transported from the Slovakian mining districts in the Carpathian Mountains via river systems down to the coastal town of Gdańsk (Danzig) in Poland. In the Middle Ages, Gdańsk was also the dominant port for exporting Polish oak timber.

“It is therefore very likely that it was in Gdańsk that the ship took on its cargo before it continued on what would be its final voyage.”

Heading for Belgium

The composition of the cargo indicates that the ship was on its way to a western European port when, for unknown reasons, it foundered in the Bohuslän archipelago. Here, too, the research team have drawn conclusions from historical sources.

“We believe that the ship’s final destination was Bruges in Belgium. In the 15th century, this city was a major trading hub. We also know that copper produced in Central Europe was shipped on from there to various Mediterranean ports, including Venice.”

The study presents recent investigations of the composition of the cargo. These results were then compared with other sources from the same period, archaeological and historical. The study has been published in the article Tracing Trade Routes: Examining the Cargo of the 15th-Century Skaftö Wreck, in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology.

Facts in brief

- The Skaftö wreck, which was discovered in 2003, dates back to the late 1430s and is believed to have sunk around 1440. The wreck was the subject of archaeological examinations between 2005 and 2009 by the Bohusläns museum under the leadership of maritime archaeologist Staffan von Arbin.

- ‘The study just published is part of Staffan von Arbin’s upcoming doctoral thesis in archaeology at the University of Gothenburg, which deals with medieval maritime transport geography in the now-Swedish region of Bohulän, which during this period was part of Norway.