Ancient erotic pottery teaches Peruvians to prevent prostate cancer

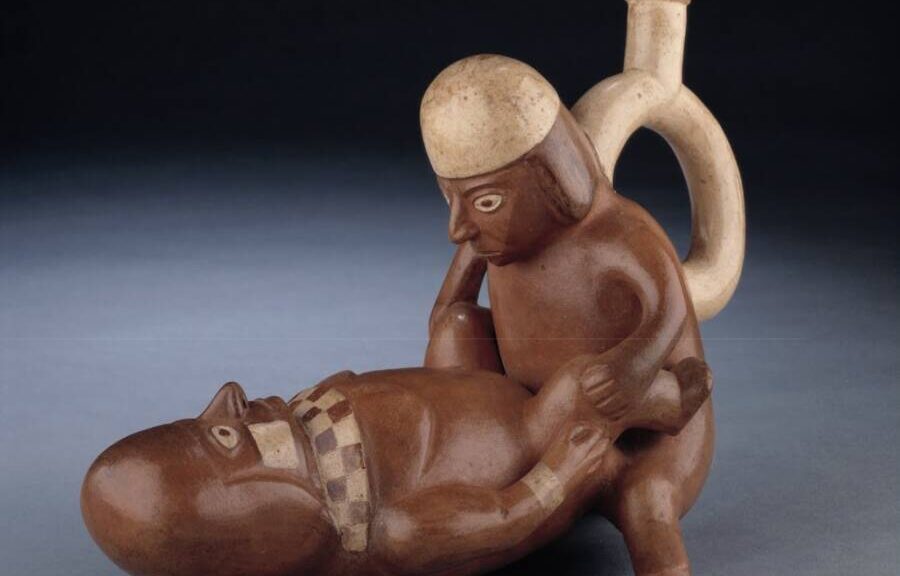

The Larco Museum in Peru boasts one of the finest collections of pre-Columbian Mochica sculptures in the world — and most of them are very sexually explicit. But rather than keep them encased in displays, the museum has recently begun to use the ancient artworks to promote self-screening for cancer.

According to Reuters, the exhibition, called “Touch the Genitals of the Mochica,” launched on Feb. 25, 2022, and allowed men to touch the sculptures, which are over 1,000 years old.

With hundreds of items on display, visitors perused a wide variety of sexualized sculptures. Depicting a range of erotic acts and sexual anatomy, these clay ceramics left some museumgoers visibly shy. Ultimately, the museum encouraged touching them to learn how to spot cancers.

“The aim is to bring closer the knowledge of our ancestors about the human body, expressed through these ceramic vessels that we call the ‘Erotic Huacos,’” said Larco Museum Director Ulla Holmquist.

The exhibit came in the wake of devastating figures regarding access to healthcare during the global COVID-19 pandemic. When the annual average of 8,700 male cancer diagnoses in Peru surpassed 10,000 in 2021, health officials perked up.

The museum partnered with the League Against Cancer, a private company that reported that 45 per cent of those diagnosed cases were too advanced to be cured.

“Timely detection of cancer of the external genitalia in men, both the penis and testicles, is very low,” said Giselle Grillo from the League Against Cancer. “Many do not know how to explore their genitals, what palpation is. With this, we give an early diagnosis.”

The men were told to feel for bumps, smooth or rough spots, and other abnormalities in the ancient art in an effort to model how to undertake a proper self-examination.

The League Against Cancer explained that men should wear gloves before lubricating one finger and then inserting it into the rectum to check for soft or hard bumps around the prostate when performing a personal screening. While the organisation is using the artwork of the Moche culture to promote as much, they’ve also posted instructions online.

The Moche culture thrived in northern Peru from about 150 C.E. through the end of the eighth century and established its capital near present-day Moche in Trujillo. With agriculture as its foundation, the civilization constructed an impressive irrigation network to nurture its crops.

Perhaps most fascinating was their art, which was primarily erotic.

The Moche culture depicted all sorts of activities in their colourful murals and handcrafted ceramics. From fishing and hunting to war and human sacrifice, their iconographies reflected their interests. However, their “huacos,” a pre-Columbian term for handcrafted ceramics, were focused on sex.

As published in the American Anthropologist journal, a 2004 study noted at least 500 huacos were sexually themed. Curiously, most of these depicted heterosexual anal sex and rarely showed vaginal penetration. Scholars believe sex symbolized circulation and flow to the Moche and honored their successful irrigation techniques, the basis of their agricultural society. Historians also posited that the loss of fluids from the human body represented the disappearance of water from the land.

Mochica art has indeed shown dying warriors bleeding from the nose or people having their eyes torn out by predators — and would catch the attention of cancer-prevention officials 1300 years later.

José Medina, a urologist with League Against Cancer, also wanted to “call on the population to undergo annual medical examinations in order to have a timely diagnosis.”

He said that self-diagnosis is only a first step that will increase early detection, and he was hopeful that the new partnership would raise awareness through its novelty.