Evidence of advanced Civilizations living on earth more than 100,000 years ago

It only took five minutes for Gavin Schmidt to out-speculate me.

Schmidt is the director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (a.k.a. GISS), a world-class climate science facility. One day last year, I came to GISS with a far-out proposal. In my work as an astrophysicist, I’d begun researching global warming from an “astrobiological perspective.” That meant asking whether any industrial civilization that rises on any planet will, through its own activity, trigger its own version of a climate shift. I was visiting GISS that day hoping to gain some climate science insights and, perhaps, collaborators. That’s how I ended up in Gavin’s office.

Just as I was revving up my pitch, Gavin stopped me in my tracks.

“Wait for a second,” he said. “How do you know we’re the only time there’s been a civilization on our own planet?”

It took me a few seconds to pick up my jaw off the floor. I had certainly come into Gavin’s office prepared for eye rolls at the mention of “exo-civilizations.” But the civilizations he was asking about would have existed many millions of years ago. Sitting there, seeing Earth’s vast evolutionary past telescope before my mind’s eye, I felt a kind of temporal vertigo. “Yeah,” I stammered. “Could we tell if there’d been an industrial civilization that deep in time?”

We never got back to aliens. Instead, that first conversation launched a new study we’ve recently published in the International Journal of Astrobiology. Though neither of us could see it at that moment, Gavin’s penetrating question opened a window not just onto Earth’s past, but also onto our own future.

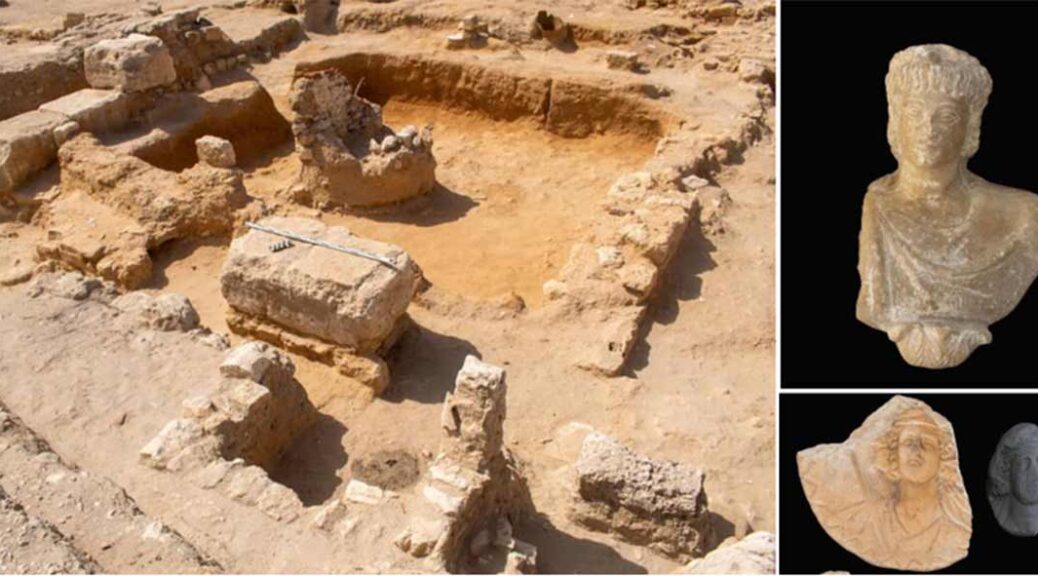

We’re used to imagining extinct civilizations in terms of sunken statues and subterranean ruins. These kinds of artefacts of previous societies are fine if you’re only interested in the timescales of a few thousands of years. But once you roll the clock back to tens of millions or hundreds of millions of years, things get more complicated.

When it comes to direct evidence of an industrial civilization—things like cities, factories, and roads—the geologic record doesn’t go back past what’s called the Quaternary period 2.6 million years ago. For example, the oldest large-scale stretch of ancient surface lies in the Negev Desert. It’s “just” 1.8 million years old—older surfaces are mostly visible in cross-section via something like a cliff face or rock cuts. Go back much further than the Quaternary, and everything has been turned over and crushed to dust.

And, if we’re going back this far, we’re not talking about human civilizations anymore. Homo sapiens didn’t make their appearance on the planet until just 300,000 years or so ago. That means the question shifts to other species, which is why Gavin called the idea the Silurian hypothesis, after an old Doctor Who episode with intelligent reptiles.

So could researchers find clear evidence that an ancient species built a relatively short-lived industrial civilization long before our own? Perhaps, for example, some early mammal rose briefly to civilization building during the Paleocene epoch, about 60 million years ago. There are fossils, of course. But the fraction of life that gets fossilized is always minuscule and varies a lot depending on time and habitat. It would be easy, therefore, to miss an industrial civilization that lasted only 100,000 years—which would be 500 times longer than our industrial civilization has made it so far.

Given that all direct evidence would be long gone after many millions of years, what kinds of evidence might then still exist? The best way to answer this question is to figure out what evidence we’d leave behind if human civilization collapsed at its current stage of development.

Now that our industrial civilization has truly gone global, humanity’s collective activity is laying down a variety of traces that will be detectable by scientists 100 million years in the future. The extensive use of fertilizer, for example, keeps 7 billion people fed, but it also means we’re redirecting the planet’s flows of nitrogen into food production. Future researchers should see this in characteristics of nitrogen showing up in sediments from our era. Likewise our relentless hunger for the rare-Earth elements used in electronic gizmos. Far more of these atoms are now wandering around the planet’s surface because of us than would otherwise be the case. They might also show up in future sediments, too. Even our creation, and use, of synthetic steroids has now become so pervasive that it too may be detectable in geologic strata 10 million years from now.

And then there’s all that plastic. Studies have shown that increasing amounts of plastic “marine litter” are being deposited on the seafloor everywhere from coastal areas to deep basins, and even in the Arctic. Wind, sun, and waves grind down large-scale plastic artefacts, leaving the seas full of microscopic plastic particles that will eventually rain down on the ocean floor, creating a layer that could persist for geological timescales.

The big question is how long any of these traces of our civilization will last. In our study, we found that each had the possibility of making it into future sediments. Ironically, however, the most promising marker of humanity’s presence as an advanced civilization is a by-product of one activity that may threaten it most.

When we burn fossil fuels, we’re releasing carbon back into the atmosphere that was once part of living tissues. This ancient carbon is depleted in one of that element’s three naturally occurring varieties or isotopes. The more fossil fuels we burn, the more the balance of these carbon isotopes shifts. Atmospheric scientists call this shift the Suess effect and the change in isotopic ratios of carbon due to fossil-fuel use is easy to see over the past century. Increases in temperature also leave isotopic signals. These shifts should be apparent to any future scientist who chemically analyzes exposed layers of rock from our era. Along with these spikes, this Anthropocene layer might also hold brief peaks in nitrogen, plastic nanoparticles, and even synthetic steroids. So if these are traces our civilization is bound to leave for the future, might the same “signals” exist right now in rocks just waiting to tell us of civilizations long gone?

Fifty-six million years ago, Earth passed through the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). During the PETM, the planet’s average temperature climbed as high as 15 degrees Fahrenheit above what we experience today. It was a world almost without ice, as typical summer temperatures at the poles reached close to a balmy 70 degrees Fahrenheit. Looking at the isotopic record from the PETM, scientists see both carbon and oxygen isotope ratios spiking in exactly the way we expect to see in the Anthropocene record. There are also other events like the PETM in Earth’s history that show traces like our hypothetical Anthropocene signal. These include an event a few million years after the PETM dubbed the Eocene Layers of Mysterious Origin, and massive events in the Cretaceous that left the ocean without oxygen for many millennia (or even longer).

Are these events indications of previous nonhuman industrial civilizations? Almost certainly not. While there is evidence that the PETM may have been driven by a massive release of buried fossil carbon into the air, it’s the timescale of these changes that matter. The PETM’s isotope spikes rise and fall over a few hundred thousand years. But what makes the Anthropocene so remarkable in terms of Earth’s history is the speed at which we’re dumping fossil carbon into the atmosphere. There have been geological periods where Earth’s CO2 has been as high or higher than it is today, but never before in the planet’s multibillion-year history has so much buried carbon been dumped back into the atmosphere so quickly. So the isotopic spikes we do see in the geologic record may not be spiky enough to fit the Silurian hypothesis’s bill.

But there is a conundrum here. If an earlier species’ industrial activity is short-lived, we might not be able to easily see it. The PETM’s spikes mostly show us Earth’s timescales for responding to whatever caused it, not necessarily the timescale of the cause. So it might take both dedicated and novel detection methods to find evidence of a truly short-lived event in ancient sediments. In other words, if you’re not explicitly looking for it, you might not see it. That recognition was, perhaps, the most concrete conclusion of our study.

It’s not often that you write a paper proposing a hypothesis that you don’t support. Gavin and I don’t believe the Earth once hosted a 50-million-year-old Paleocene civilization. But by asking if we could “see” truly ancient industrial civilizations, we were forced to ask about the generic kinds of impacts any civilization might have on a planet. That’s exactly what the astrobiological perspective on climate change is all about. Civilization building means harvesting energy from the planet to do work (i.e., the work of civilization building). Once the civilization reaches truly planetary scales, there has to be some feedback on the coupled planetary systems that gave it life (air, water, rock). This will be particularly true for young civilizations like ours still climbing up the ladder of technological capacity. There is, in other words, no free lunch. While some energy sources will have a lower impact—say solar versus fossil fuels—you can’t power a global civilization without some degree of impact on the planet.

Once you realize, through climate change, the need to find lower-impact energy sources, the less impact you will leave. So the more sustainable your civilization becomes, the smaller the signal you’ll leave for future generations.

In addition, our work also opened up the speculative possibility that some planets might have fossil-fuel-driven cycles of civilization building and collapse. If a civilization uses fossil fuels, the climate change they trigger can lead to a large decrease in ocean oxygen levels. These low oxygen levels (called ocean anoxia) help trigger the conditions needed for making fossil fuels like oil and coal in the first place. In this way, a civilization and its demise might sow the seed for new civilizations in the future.

By asking about civilizations lost in deep time, we’re also asking about the possibility for universal rules guiding the evolution of all biospheres in all their creative potential, including the emergence of civilizations. Even without pickup-driving Paleocenians, we’re only now learning to see how rich that potential might be.