Did Hindu’s build Egyptian Pyramids?

Egyptian Pyramids, Mayan Pyramid Temples, Babylonian Ziggurats (Shikara in Sanskrit) and Hindu temples—all look like a cone. The design and structure are same. Hindus were the originators. Hindus taught the world that God lives in a high place-sacred mountain MERU.

The Greeks changed the name to Mount Olympus. Hindus are the only race in the world continuing temple buildings in the same way and worshipping God in it. All others made them as museums.

We took this concept of ‘sacred mountain’ to Cambodia and built the largest temple complex in the world Angkor Wat and Borobudur in Indonesia. We used the temple for Gods, where as others used them for God like kings.

Scholars around the world knew the connection between India and Egypt from 1400 BC. That was the time Mittanni King Dasaratha wrote ten letters (it is available in all the encyclopaedias as Amarna letters) after marrying his daughter to Egyptian king Amhenotep (Sramana Dev). Tushratta/ Dasaratha was a king who ruled Syria (now a Muslim country), but his name and his forefather names are in Sanskrit.

To confirm they are Indian Hindus we have an inscription giving the Vedic Gods Mitra, Varuna, Indra and Nasatya (Asvini Devas) in an agreement with the Hittites and a horse manual with Sanskrit numbers.

(Though all these things were in encyclopaedias from 1930s, the ruling British were very careful not to teach this or about South East Asian Hindu Empire to Indian History students. All these excavations were done by non British scholars! British were very successful in sowing the poisonous seeds of divisive Aryan Dravidian Invasion theory which is not in Sangam Tamil or Sanskrit literature.

They carefully hid facts like Tamils worshipped Indra, Varuna, Vishnu, Skanda and Durga which was found in the oldest Tamil book Tolkappiam).

Bible which was put to writing around 945 BC (Hutchinson Encyclopaedia) also gave Sanskrit words for imports from India such as karpasa (cotton),Tuke (Siki for peacock or Suka for parrots), Kapi (monkey)etc.

But many of us do not know that the first king of Egypt was Manu, the law giver. But they were not Dasaratha of Valmiki Ramayana or Manu of Manu Dharma Sastra.

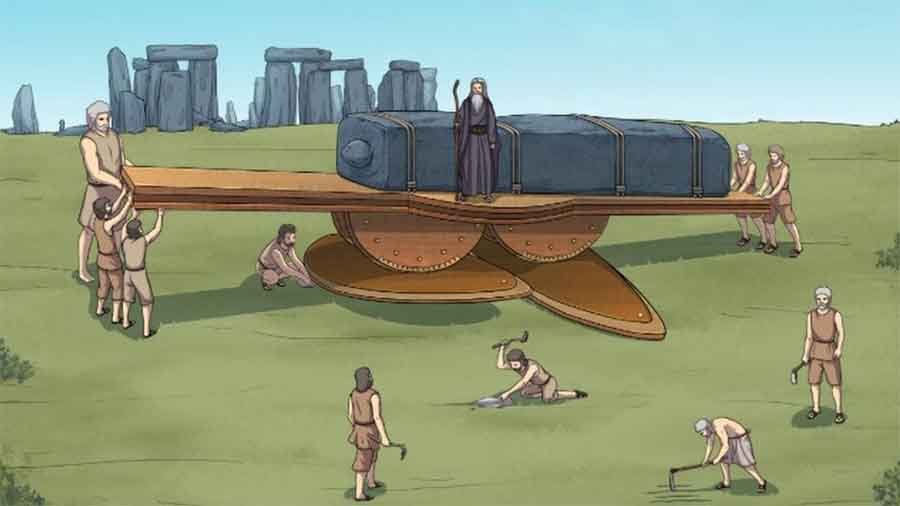

Many of us do not know that the Egyptian builders used the Sanskrit word Sutra for measurements during building Egyptian Pyramids.

Sulba Sutras are Vedic manuals giving measurements for Yaga Kundas (fire pits for sacrificial fire ceremonies). It contains Pythagorean Theorem and other Vedic mathematics. Sutra means thread/plumb line,also book of formulas.

Arta Dama, a Mittanni king, married his daughter to Egyptian king Tuthmose IV and the daughter of Sutharna was married to Amenhotep III (1390 BC). Another daughter was married to his son Akhenaten.

He was the most revolutionary king who established ONE GOD for the Egyptians. His name in Sanskrit means Eka Aten (One Aten is God). He worshiped Surya (sun).

Egyptian kings’ sun worship looks exactly like Brahmins doing Sandhyavandhana. Brahmins do it thrice a day facing sun. Egyptian kings worship the sun in the same way.

Manu=Nara Meru

In my earlier posts I have established that the big conflict between Krishna/Arjuna pair and the Nagas under the leadership of Maya Dhanava just before 3100 BC resulted in a mass exodus of Nagas to South America and Central America.

After Krishna’s burning of Naga lands (Kandava vana) in the Gangetic plains, there were continuous clashes. It was followed by the mass execution of Nagas (Sarpa Yagna) to avenge the assassination of King Parikshit by the Nagas. A Naga hid himself in the fruit basket and killed King Parikshit.

Around 3100 BC another dynasty started their rule in Egypt. Since they were Hindus, they named the first king Manu (Manes). His other name was Narmer i.e. Nara Meru, a pure Sanskrit word meaning Mountain among the Kings. Meru was the holiest and highest mountain in Hindu Mythology. Any high point was named Meru.

We have different Merus around the world. Pameru (Pamir Plateau), KuMeru (Kumari in the South of India). Su Meru (Sumerians) of the Middle East. The word Khmer of Cambodia may be related to Kumari/Ku Meru. I will write about it separately. North and South Poles were also called Merus in Hindu Mythologies (Puranas).

Menes was given a legendary date 3100 BC by the Greeks because Indian Kaliyuga Calendar begins in 3102 BC. Mayans also followed this Kali Yuga Calendar. (Full details are in my posts)

Menes (Manu) was praised the first Law Giver of Egypt by the Greek Historian Diodorous Siculus. Egyptians were just like Indian Hindus. They believed kings were half God, half man. Indian words for kings and palaces are synonymous with Gods and Temples. Diodorous links Heracles (Hercules) with Egypt and India. Hercules was one of the 12 ancient Gods of Egypt and he cleared India of wild animals, says Diodorous.

Narmer palette shows his picture as a strict man punishing the wrong ones.

( In Tamil Khon means King and God, Koil means Palace and temple, In Sanskrit Deva is used for Lord and the King). Khon became Khan in other languages like Kesari/lion gave a new word Caesar. Tele in the Ancient Middle East means temple, which is the corrupted form of Sanskrit word STHALA. Tamils changed it to Thali=temple)

Egyptian kings called themselves children of Surya/sun. This corresponds with the Surya Vamsa of Hindu scriptures. Like Indian Hindu kings, Egyptian kings had two names : 1. Name given at birth 2. Coronation name or Abisheka Nama.

Nile River (Sanskrit word)

River Nile is known as Blue Nile because of its BLUE colour. It is a Sanskrit word NILA meaning blue. If I find only one Sanskrit word from among 1000 place names in Egypt, scholars will laugh at me. But almost all ancient Egyptian names are Sanskrit names. (Just a few examples: Heliopolis= Suryapura, Thebes=Devas, Zawyet el Aryan=Arya of ?, Saqqara= Chakra, Dashuf= Dasyu or Dasa, Asyut=Achyuta, Hierakonpolis=Swarnapura, Amra, Amarna= Amara, Dishashasa=Disa, El Badari= Badri (nath), Beni Hasan=Vani dasan, Naj el der=Naga….?). Please note that Greek words are also in many place names.

Ramses=Rama Seshan?

Ramses is a title for at least seventeen kings in Egypt. Kanchi Paramacharya Swamiji has mentioned this is the name of Rama, Hero of Ramayana, in his 1932 Chennai lectures.

Naga on their heads

Many of the kings have Naga ( Naga gave birth to English word Snake=S+Naka) on their heads. There is no Hindu God without snake on their bodies. But Egyptian Kings look exactly like Lord Shiva of Hindu mythology. Another word for snake is Uraga=Uraes of Egypt.

Belief in Rebirth

The reason for building Pyramids was their belief in after life and rebirth. All the oriental religions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism) believe in after life and Rebirth. Semitic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam) don’t believe in it. This shows very clear connection with the Hindus of India. In Indian mythology we have Nimi (see the Puranas) saving his body like the Egyptians.