A Stunning Jade mask discovered in the tomb of the Maya King in Guatemala

Archaeologists excavating a looted pyramid tomb in the ruins of a Mayan city in Peten, northeast Guatemala, have discovered a mysterious interlocking jade mask believed to have belonged to a previously unknown Mayan king.

Chochkitam, a little-known archaeological site, is located near the Peten Basin, a subregion of the Maya Lowlands in northwest Guatemala.

The area is considered the heartland of the Maya Classic Period, which lasted from 200 to 900 AD.

The site was first reported in 1909, and ongoing studies have revealed three major monumental groups linked by a long central causeway.

In ancient times, the value of jade went far beyond its material value. Mayans considered it a protector of generations, living and dead. For this reason, jade masks were generally used to symbolize deities or ancestors and were used to reflect the affluence and influence of the entombed individuals.

Archaeologists discovered that grave robbers had excavated a tunnel into a royal pyramid’s core following a LiDAR survey in 2021. Further inspection revealed that the intruders had overlooked a specific area within the pyramid’s inner chamber.

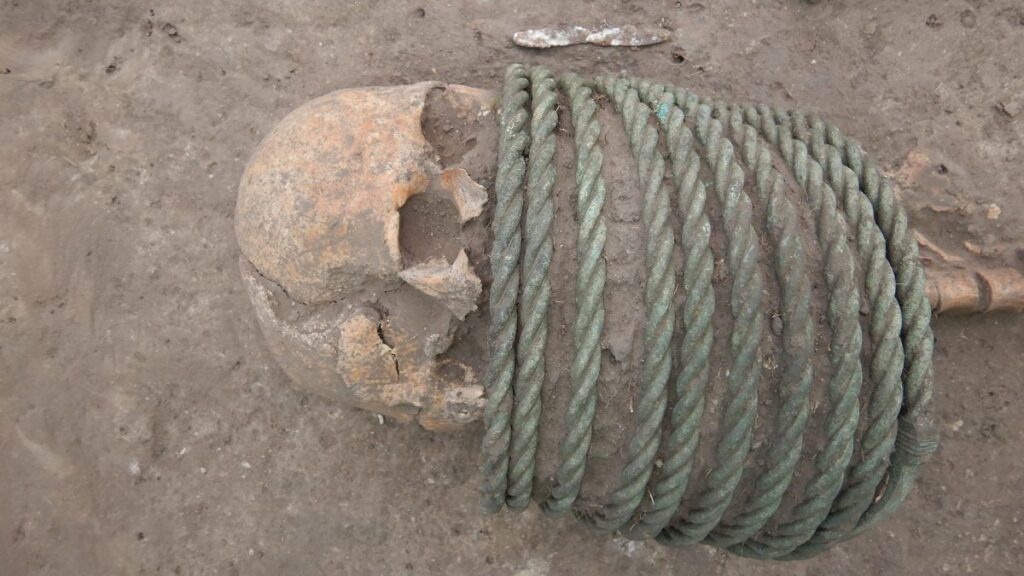

A human skull, and bones, some of them carved with hieroglyphs, a coffin-shaped stone box, ceramic artifacts, and funerary offerings including a pot, oyster shells, and multiple jade pieces that fit together to create a jade mask were found as a result of this oversight.

The name Itzam Kokaj Bahlam is spelled out in carvings and hieroglyphs on some of the bone fragments.

The researchers surmise that this name may belong to the buried Maya king who ruled Chochkitam approximately 350 AD.

The most fascinating feature of all is that a carving on one of the bones shows the ruler clutching the head of a Maya deity, precisely like the assembled jade mask.

All the artifacts and bones discovered in the Chochkitam tomb were brought to the Holmul Archaeological Project (HAP) lab for cleaning and field analysis.

It was there that archaeologists put together the single blocks of jade that they had unearthed, and they were able to reconstruct an entire jade mosaic mask.

Lead archaeologist Francisco Estrada-Belli of Tulane University and his team discovered the burial using LIDAR mapping technology, according to an extensive article in National Geographic. The mask represents a manifestation of the Storm God worshiped by the Mayans.