Archaeologists Discover 3,500-Year-Old “Griffin Warrior” Tomb Full of Treasures

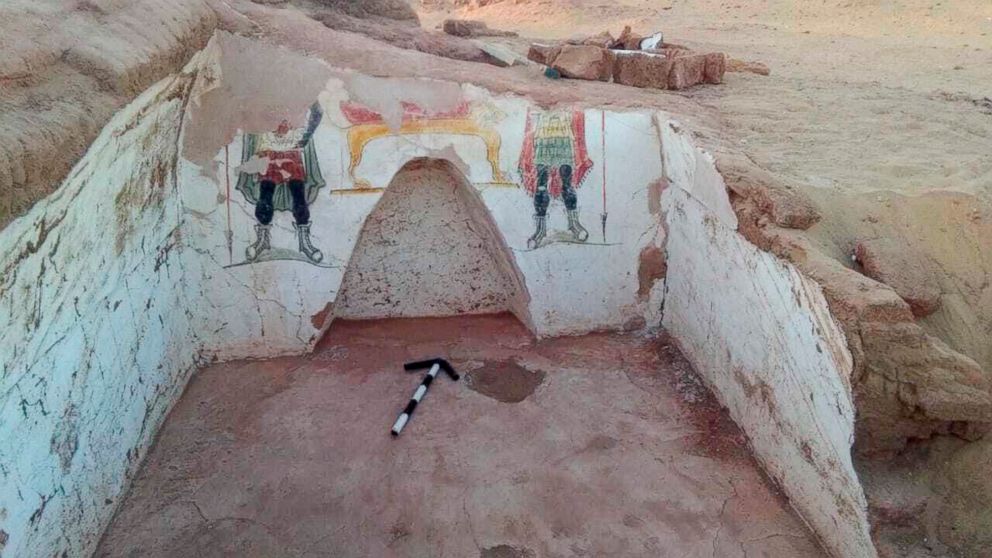

Jack Davis and Sharon Stocker, archaeologists in UC’s classics department, found the two beehive-shaped tombs in Pylos, Greece, last year while investigating the area around the grave of an individual they have called the “Griffin Warrior,” a Greek man whose final resting place they discovered nearby in 2015.

Like the Griffin Warrior’s tomb, the princely tombs overlooking the Mediterranean Sea also contained a wealth of cultural artefacts and delicate jewellery that could help historians fill in gaps in our knowledge of early Greek civilization.

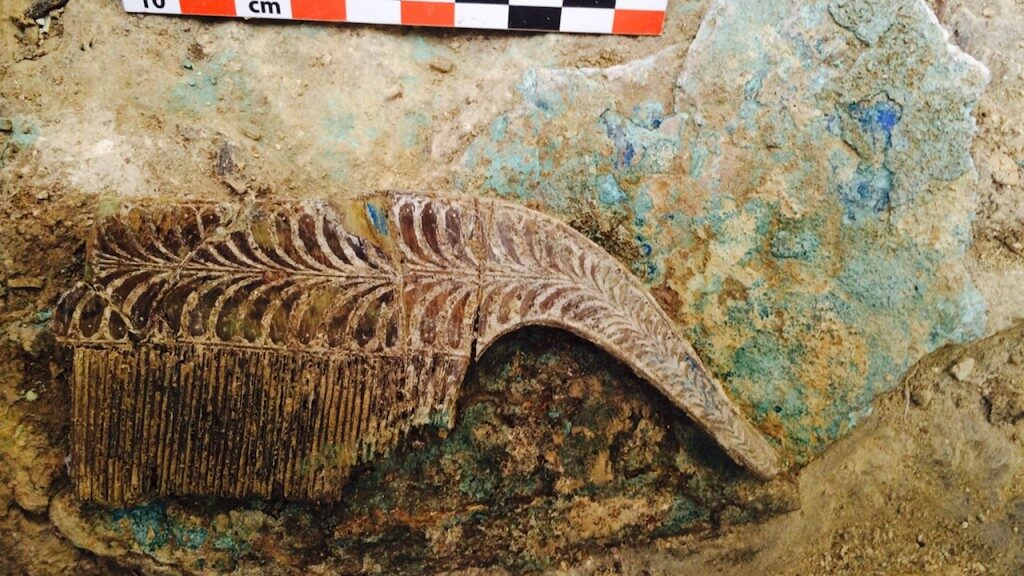

The warrior was buried with a bronze sword, ivory combs, gold rings, and seal stones, gemstones carved with images depicting Minoan influences. Although the archaeologists don’t yet know where in Greece the griffin warrior was from, it’s clear from the wealth of objects found in his grave that he held a high station in society, and the particulars of the object are leading archaeologists to revise some accepted theories about Mycenaean Greece.

The warrior was buried with a bronze sword, ivory combs, gold rings, and seal stones, gemstones carved with images depicting Minoan influences. Although the archaeologists don’t yet know where in Greece the griffin warrior was from, it’s clear from the wealth of objects found in his grave that he held a high station in society, and the particulars of the object are leading archaeologists to revise some accepted theories about Mycenaean Greece.

The discovery was made near the southwest coast of Greece, close to the Palace of Nestor, which is part of the Pylos Regional Archaeological Project. The palace, named for King Nestor of Pylos in Homer’s The Illiad, is one of the best-preserved Bronze Age palaces on the Greek mainland, despite having been nearly destroyed by fire in 1200 BCE. Dr. Sharon Stocker and Dr. Jack W. Davis from the University of Cincinnati have been excavating at Pylos for the past 25 years.

The Palace of Nestor is an incredible source of archaeological information, though it has been more than 75 years since the last discovery of this magnitude: in 1939, Carl Blegen unearthed a number of tablets inscribed with Linear B script, writing that, borrowing heavily from the Minoan Linear A script, became the earliest known form of written Greek.

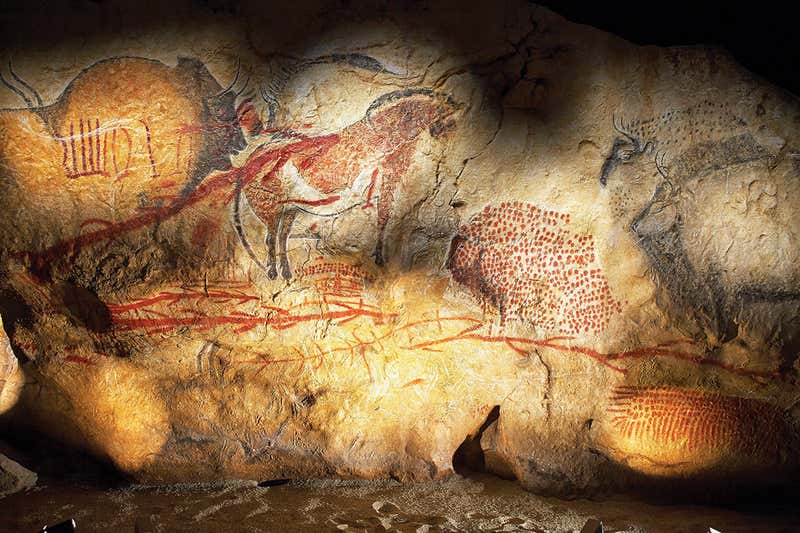

Like the Linear B tablets, many of the objects found in the Griffin Warrior’s tomb display Minoan imagery, such as bulls and bull-leaping, a seemingly impossible athletic feat where a person jumps over a charging bull. These images of bull-leapers, also known as Toreadors, are common in Minoan culture and can be seen in many places, such as the stucco frescoes at the Palace of Knossos, The archaeologists have determined that the Griffin Warrior predates the Palace of Nestor, which might point to Mycenaean Greece flourishing earlier than previously thought in Pylos. Mycenaean Greece (1600–1100 BCE), the first advanced culture on the mainland, was a civilization in transition.

After mainland Greece invaded and occupied Minoan Crete around 1420 BCE, Greeks began to adapt, rather than destroy, the more sophisticated Minoan culture. Dr Davis believes that the presence of Minoan imagery on the Griffin Warrior’s artefacts “suggests that contact between Crete and Greece were very close… and that here in Pylos they… were in the process of incorporating Minoan ideas into their own ideology.”

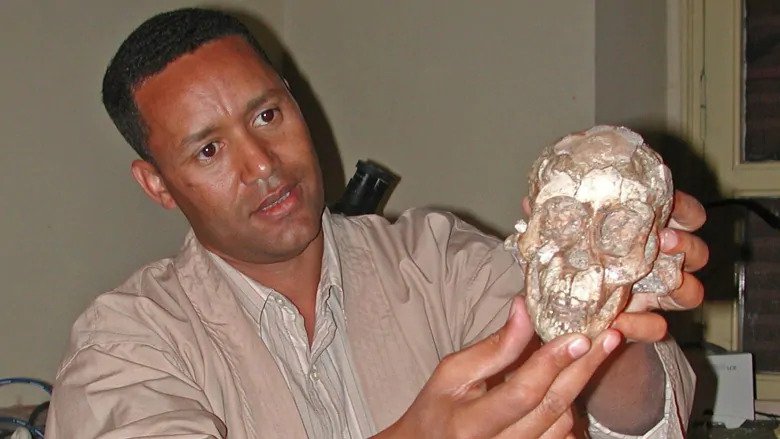

The archaeologists hope to do DNA testing on the Griffin Warrior’s teeth to try to determine his birthplace, which might help explain the meaning and purpose of the Minoan rings and stones in his tomb — e.g., whether these artefacts were personally important to him, aspects of Minoan culture that had been adopted by the Mycenaean people, or had been looted from Crete.

The Griffin Warrior’s discovery and further investigation into his birthplace might lead archaeologists to further reevaluate the history and timeline of Mycenaean Greek culture and its relation to Minoan Crete. This finding has revealed a wealth of new information, but work continues at the Pylos dig site to see how much more can be illuminated about Mycenaean Greece.