Vast cemetery of Bronze Age burial mounds unearthed near Stonehenge

Archaeologists have discovered a vast cemetery of Bronze Age burial mounds, thought to be up to 4,400 years old, ahead of a building development less than 10 miles (16 kilometers) from Stonehenge.

The cemetery includes more than 20 circular mounds, known as barrows, built between 2400 B.C. and 1500 B.C. on a chalk hillside near Harnham on the outskirts of Salisbury in southwest England.

Other than the site’s proximity to Stonehenge, there’s no evidence that the cemetery was connected with the famous monument. But the barrows were built around the same time as some of the central stages of Stonehenge, according to a statement from Cotswold Archaeology, a private firm conducting the excavations.

Many archaeologists now think Stonehenge, too, was mainly a burial ground, although it also may have functioned as a communal gathering place or even a calendar.

The newfound barrows range in size, with the smallest measuring about 33 feet (10 meters) across and the largest spanning 165 feet (50 m). But most of the barrows are between 65 and 100 feet (20 and 30 m) across.

Ancient barrows

The barrows at the cemetery are grouped in “pairs or small clusters of six or so,” Alistair Barclay, an archaeologist at Cotswold Archaeology and the site’s post-excavation manager, told Live Science in an email.

After arriving at the site in 2022, the archaeologists have now fully excavated five barrows in two areas. Four of the barrows had previously been identified, but the fifth was unknown, possibly because it had been covered by loose soil washed down from an uphill area.

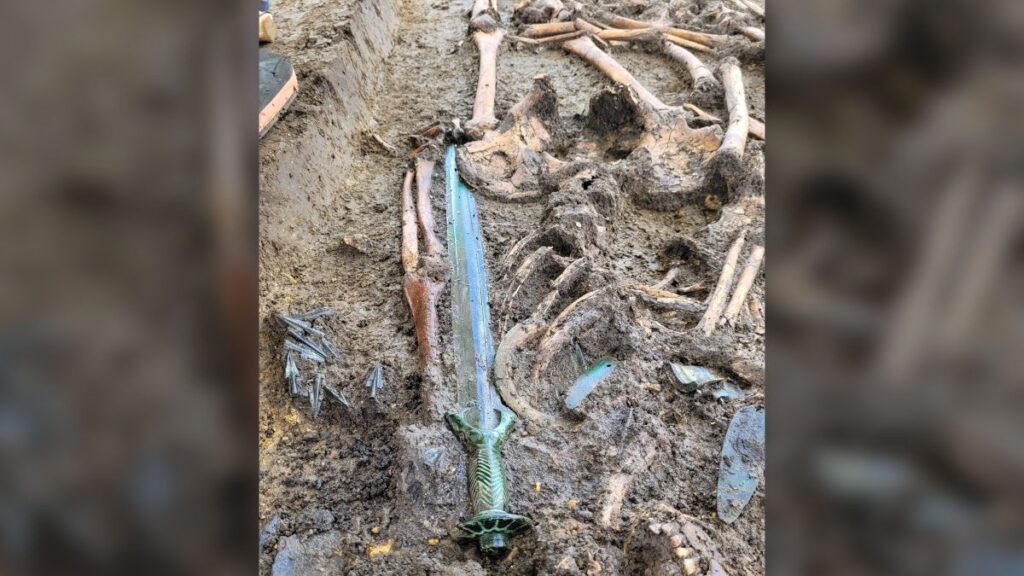

One of the barrows was originally enclosed by an oval-shaped ditch that was replaced in prehistory with a nearly circular ditch. That suggests this barrow might have been built before the others, during the Neolithic period, which ended around 2400 B.C.; a mass grave near its center held the skeletal remains of adults and children, the statement said.

The oval ditch also cut through pits of red deer (Cervus elaphus) antlers, which were highly prized in the Neolithic for making tools, ritual artifacts, and small items like pins and combs.

The antlers will now be checked for signs of deliberate breakage or wear that could indicate they were once used to make tools, the statement said.

Prehistoric burials

The archaeologists have excavated the remains of nine other burials and three artifacts from graves among the barrows. In some cases, the grave goods were pottery “beakers” — distinctive round drinking vessels — indicating that the people buried there were from the Bronze Age “Bell Beaker culture,” which was widespread in Britain after about 2450 B.C.

The Cotswold Archaeology team has also found evidence of later occupations at the site, including what may be traces of an Iron Age cultivation area. It consists of more than 240 pits and postholes.

Some of the pits may have been used to store grain, but most were used for discarding rubbish — a boon to archaeologists studying how people lived and farmed the land at that time.

The team also found evidence of a Saxon building at the site, along with other artifacts from the Anglo-Saxon age (fifth to 11th centuries A.D.)