Five 1,500-Year-Old Gold Foil Figures Unearthed in Norway

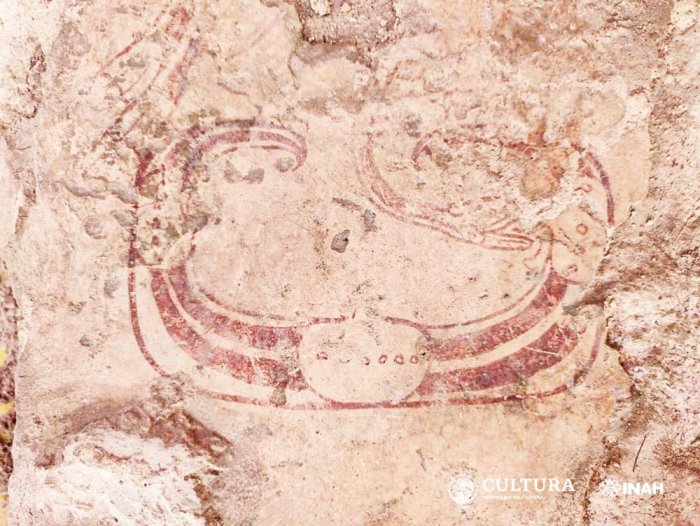

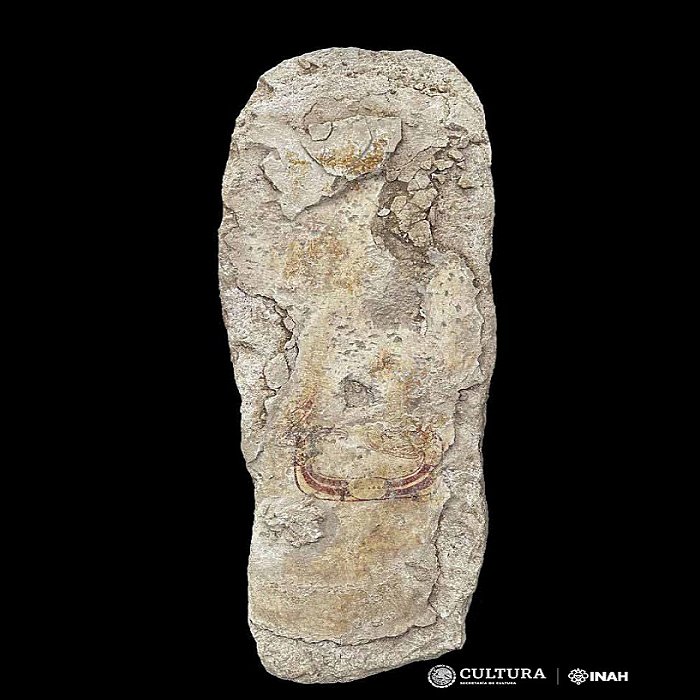

The pieces are tiny, about the size of a fingernail. They are flat and thin as paper, often square, and stamped with a motif. Usually, they depict a man and a woman in various types of clothing, jewellery, and hairstyles. They are from what we call the Merovingian period in Norway, which starts around 550 and goes into the Viking Age. A time of turbulent climates and turbulent power relations.

In previous excavations, archaeologists have found 30 such gold foil figures here at Hov, connected to what the archaeologists believe was once a temple where people worshiped and made sacrifices to the gods. The archaeologists had talked about how they should not be disappointed if they did not find more gold foil figures this time.

But then something sparkled in the ground.

“It was incredibly exciting,” archaeologist Kathrine Stene says.

She is the project leader for the excavation, which has been ongoing along the road here all summer and into autumn, due to the upgrade of the E6 highway between Mjøsa Bridge and Lillehammer.

A religious offering?

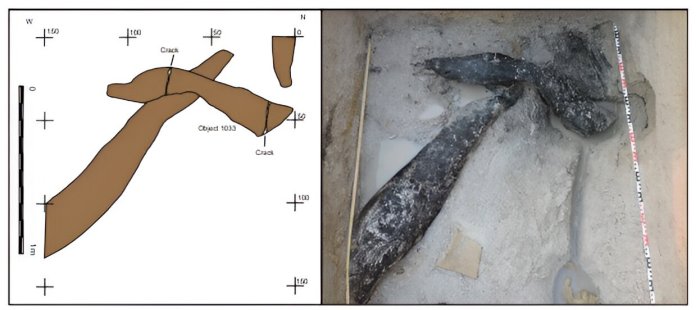

Archaeologists have found five gold foil figures in the last couple of weeks. Three of them were found where the wall of the temple once stood. Two of them were found in separate post holes.

Finding a gold foil figure is spectacular and rare in itself. But the five gold foil figures that were found at Hov this time offer something extra: They were found and excavated where they were most likely originally placed. Knowing where something was once placed helps archaeologists understand more.

“It’s extra special that we can link the gold foil figures to the various parts of the building’s construction,” Stene says.

The many gold foil figures found here earlier were discovered in and around another post hole in the old temple, on the opposite side of the two that recently appeared.

It’s possible that some of the gold foil figures they found here earlier were also placed in the wall, but there’s uncertainty about exactly where they were once found. Now, with these three that we found under the actual structure of the wall, it’s clear that they were intentionally placed there before the wall’s construction,” Stene says.

One of the theories about what the gold foil figures were used for is that they may have served as a form of admission ticket to a temple like the one that once stood here at Hov.

But an admission ticket doesn’t lie under a wall.

“Modern excavation has provided more knowledge about this,” Stene says. “The gold foil figures in the post hole were not visible to people. Those we found in the wall would also not have been visible to others. So this doesn’t appear to be an admission ticket, but rather an offering or a religious act to protect the building.”

A small but prominent pagan temple

The temple at Hov was discovered by pure chance in 1993. County conservator Harald Jacobsen drove along the E6 and noticed the soil. He thought it looked like what archaeologists call cultural layers, meaning soil where traces of humans are found. A small investigation proved that he was right, and the finding of two gold foil figures indicated that this was no ordinary place.

Smaller excavations during the 2000s led to the discovery of 28 gold foil figures, and what is referred to as a temple, a house for pagan religious practices.

One of the reasons archaeologists believe this was a temple, besides the gold foil figures, is the absence of other finds that would be natural if people lived there, like cooking pots and whetstones.

A proper excavation of the area had to wait until this year, in connection with the E6 Roterud-Storhove road project. Throughout the autumn and winter, C14 dating will finally determine if it is true that the temple has stood here since around the year 600 – and right up to the 11th century.

“Based on what we have interpreted as post holes, it’s not unreasonable to think that a building has stood here that has looked the same for several hundred years. That’s not a problem, as long as you maintain the building by replacing the load-bearing posts as they rot,” Stene says.

With its 15–16 metres in length, the house is small. Residential homes of the time could easily be 20-30 metres long.

“Because it’s relatively small, we believe the structure served a solely ritualistic function,” says Stene. “It probably wasn’t where they had their feasts. Those were likely held in a larger hall, but maybe they had drinking ceremonies here. Maybe it was just the select circle in society, the elite, who were allowed to enter.”

The archaeologists also believe the building was fairly tall.

“It probably stood out in the landscape. If you came to Mjøsa by boat, it was probably clearly visible,” Stene says.

Out looking for gold foil figures?

In Norway, findings of gold foil figures are rare. The 35 from the temple in Vingrom represent the largest collection we have found in this country.

In a similar temple in Uppåkra in Sweden, archaeologists found 100 gold foil figures.

On the Danish island of Bornholm, over 2,500 gold foil figures were found in a field.

Were there not so many gold foil figures in Norway at that time, or have we just not found them?

“There must be more of them here,” Stene believes.

But most archaeological excavations today are commissioned.

“We dig when new roads and buildings are going to be built, this limits what we can investigate. It’s about being lucky and getting the opportunity. A lot of coincidences are involved here. They are so small, but they shine when you find them. There are probably more out there,” she says. Archaeologists may have found a Viking house the length of almost two tennis courts

Gold foil figures in buildings

Ingunn Marit Røstad, archaeologist at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo, is an expert on the Merovingian period in Norway and gold foil figures. She also believes there are more gold foil figures out there.

“Bornholm is very special, even in Denmark. There aren’t that many other find sites there,” Røstad points out.

There are also other regional differences: In Denmark, there are more individual figures, whereas in Norway and Sweden, it is mostly couples that are depicted.

“But more of these small pieces of gold keep appearing. Either through excavation or with metal detectors. So, more could pop up in various places in Norway as well,” she says.

Due to the continuous new finds, the number of gold foil figures must be regularly updated. The latest numbers Røstad has from 2019 indicate that a total of 3,243 gold foil figures have been found in Scandinavia – 2,708 of them on Bornholm.

Røstad also points out that what’s especially unique about the new gold foil figures from Hov is that they were found in the ground, where they lay. Archaeologists call it context – the place where something is found is part of the story.

“Of all the thousands of gold foil figures we have, only a few have been found on-site and excavated,” Røstad says. “So, it’s extremely valuable that we get good context for the finds from Hov.”

What stands out when gold foil figures are actually excavated – as opposed to just being randomly found in a field – is that archaeologists find them in association with buildings.

Pictures of the elite

Røstad does not place much stock in the theory that the gold foil figures were admission tickets to the temple. They do not have holes suggesting that they were sewn onto clothing, and apart from a few exceptions from Bornholm, they do not have fastenings suggesting they are jewellery. They are dated to the Merovingian period due to the style of clothing and jewellery depicted on the men and women.

“People assume that they’re showing the elite’s clothing during this period,” Røstad says. “A sort of idealised depiction of elite clothing, featuring the elaborate hairstyle that the women have with a distinctive knot. You also see beads, special types of brooches, drinking cups, and drinking horns, which date them to the Merovingian period.”

A common interpretation of the gold foil figures is that they have some sort of ritual significance. Many believe that the couple depicted is the god Frøy and the goddess Gerd. Perhaps the gold foil figures were part of a symbolic act when people celebrated weddings?

Of divine lineage?

Another interpretation deals with the idea that the most powerful families of this time claimed they could trace their lineage back to the gods, and that the gold foil figures in some way signaled that they were of divine lineage.

“This was used to legitimise ruling; you were a leading family because you were descended from the gods,” Røstad says. “Even though they’re tiny, the gold foil figures could have been very significant. Not as jewellery worn visibly to show status, but perhaps they were part of some kind of ritual placement at the high seat where the king or jarl sat.”

The first gold foil figures were found in 1725. In a text from 1791, they were referred to as ‘gullgubber’ (golden old men), and the name just stuck. Even though the vast majority of them actually depict both a man and a woman.