Unique and very well-preserved prehistoric engravings found in southwestern Catalonia

Significant prehistoric rock art has been discovered in La Febro, in southwestern Catalonia. The team that discovered the art inside Cova de la Vila described it as “exceptional, both for its singularity and excellent state of conservation.”

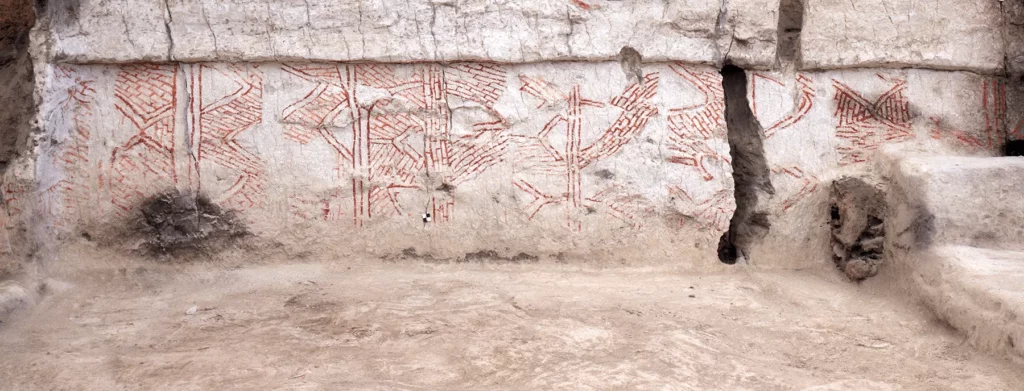

In the Cova de la Vila cave in La Febró (Tarragona), in northeastern Spain’s region of Catalonia, more than 100 prehistoric engravings have been found, arranged on an eight-meter panel.

According to experts, it is a composition related to the worldview of agricultural societies and farmers of the territory. One of the singularities of this mural is that it is made exclusively with the engraving technique, with stone or wood tools.

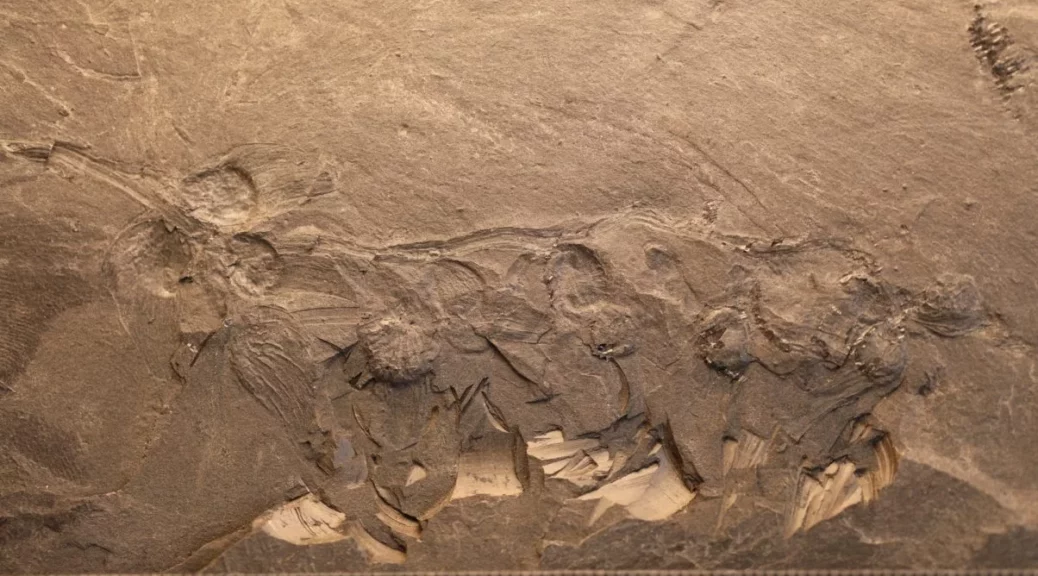

The engravings include shapes that resemble horses, cows, suns, and stars.

Julio Serrano, Montserrat Roca, and Francesc Rubinat were the cavers responsible for the discovery; they collaborated with Josep Vallverd, Antonio Rodrguez-Hidalgo, and Diego Lombao, researchers from the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES-CERCA), and Ramón Vias, an expert in prehistoric rock art.

It was in May 2021, during some scans and topographical work by a group of speleologists in the Barranc de la Cova del Corral, that they discovered the Cova de la Vila, a cavity excavated by Salvador Vilaseca in the 1940s and whose coordinates appear to have been lost.

The set is very homogeneous stylistically and presents few overlaps. From the stylistic point of view, the set is part of the post-Paleolithic schematic art. It is an art associated with peasant and livestock communities during the transition period between the Chalcolithic and the Bronze Age, that is, between 5,000 and 3,000 years BC.

In Catalonia, these types of ensembles, in underground cavities, are very rare, being the case of the Sala dels Gravats of the karstic complex of Cova de la Vila exceptional for being inside a cave and possibly associated with an archaeological context.

These types of representations are uncommon in Catalan territory, though some examples can be found, such as the Vallmajor Cave in Albinyana, Baix Penedès. In the peninsular area, it would be classified as “underground black schematic and abstract schematic,” which are heterogeneous groups distinguished by their formal or typological, thematic, and technical affinities.

La Pileta and Nerja in Málaga, La Murcielaguina in Córdoba, and the Los Enebralejos caves in Segovia, the Galera del Flex in Burgos, or the Maja Cave in Soria are some Andalusian caves with painted (black or red) or engraved representations and similar chronologies.

The engravings are in exceptional condition, but they are extremely fragile due to the instability of the support on which they are found. Because it is a soft and humid surface, changes in the atmospheric conditions in the room may affect the conservation of the panel.

To ensure these climatic conditions, the Department of Culture, the Febró Town Hall, and the IPHES collaborated to close it both outside and inside, ensuring its physical conservation. Similarly, a closure has been installed in the access to the cat flap, which provides direct access to the Sala dels Gravats, to return it to the climatic conditions it had prior to discovery.

A unique set of engravings

The rock art collection of the Sala dels Gravats of the Cova de la Vila karstic complex is completely unique. Despite the fact that its research phase has not yet begun, all indications point to it being one of the best compositions of post-paleolithic subterranean abstract art in the entire Mediterranean region.

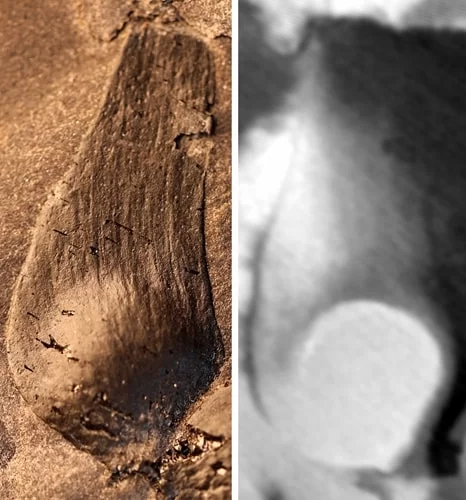

On one of the cave walls, a large number of schematic representations have been discovered. The engraving panel is made up of five horizontal lines, one on top of the other, with different engraved figures that each have their own meaning and symbolism.

Various figures such as quadrupeds, zigzags, linear, angular strokes, and circles are represented. There are several zoomorphs (possibly bovids and equines), steliforms (single and/or stars), and reticulates that stand out. There’s also a composition that looks like an ‘eyeballed’ idol. The overall aesthetic is very consistent, with few stylistic overlaps.

The distribution of the various elements suggests that it could be a composition: zoomorphic in the lower part of the panel, reticulated, particularly in the central part, and steliform in the upper part of the group, with an eye in the upper part of the group.