The earliest known depiction of biblical heroines Jael and Deborah was discovered at a Jewish synagogue in Israel

The earliest known depiction of biblical heroines Jael and Deborah was discovered at a Jewish synagogue at Huqoq in Israel,

A team of specialists and students led by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill professor Jodi Magness recently returned to Israel’s Lower Galilee to continue unearthing nearly 1,600-year-old mosaics.

The team continues its 10th season of excavation this summer at a synagogue in the ancient Jewish village of Huqoq in Lower Galilee. Discoveries made this year include the first known depiction of the biblical heroines Deborah and Jael as described in the book of Judges.

This season, project director Magness, the Kenan Distinguished Professor of religious studies in Carolina’s College of Arts and Sciences, and assistant director Dennis Mizzi of the University of Malta focused on the southwest section of the synagogue, which was built in the late fourth-early fifth century C.E.

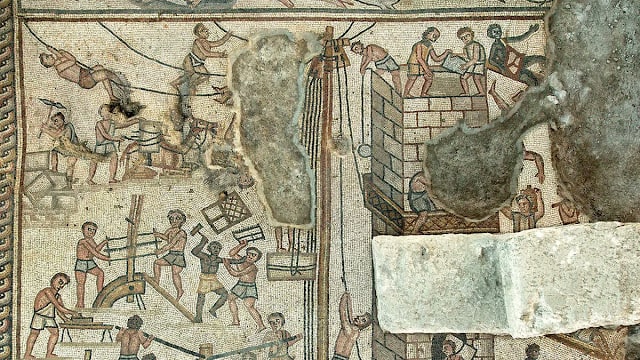

The newly discovered mosaic panels depicting the heroines are made of local cut stone from Galilee and were found on the floor on the south end of the synagogue’s west aisle.

The story of Deborah, a judge, and prophet who helped Israelite general Barak defeat the Canaanite army, is found in the fourth chapter of the Book of Judges.

After the victory, the passage says, the Canaanite commander Sisera fled to the tent of Jael (Yael-a Kenite woman), where she drove a tent peg into his temple and killed him.

The uppermost register of the newly-discovered Huqoq mosaic shows Deborah under a palm tree, gazing at Barak, who is equipped with a shield. Only a small part of the middle register is preserved, which appears to show Sisera seated. The lowest register depicts Sisera lying deceased on the ground, bleeding from the head as Jael hammers a tent stake through his temple.

A fragmented Hebrew dedicatory inscription inside a wreath is also among the newly unearthed mosaics, which are flanked by panels measuring 6 feet tall and 2 feet wide and depicting two vases with budding vines. The vines form medallions that frame four animals eating clusters of grapes: a hare, a fox, a leopard, and a wild boar.

Sponsors of the project are UNC-Chapel Hill, Austin College, Baylor University, Brigham Young University, and the University of Toronto.

Students and staff from Carolina and the consortium schools participated in the dig. Financial support for the 2022 season was also provided by the National Geographic Society, the Loeb Classical Library Foundation, the Kenan Charitable Trust, and the Carolina Center for Jewish Studies at UNC-Chapel Hill.

The mosaics have been removed from the site for conservation, and the excavated areas have been backfilled. Excavations are scheduled to continue in the summer of 2023.