Skeleton With Stone-Encrusted Teeth Found In Mexico Ancient Ruins

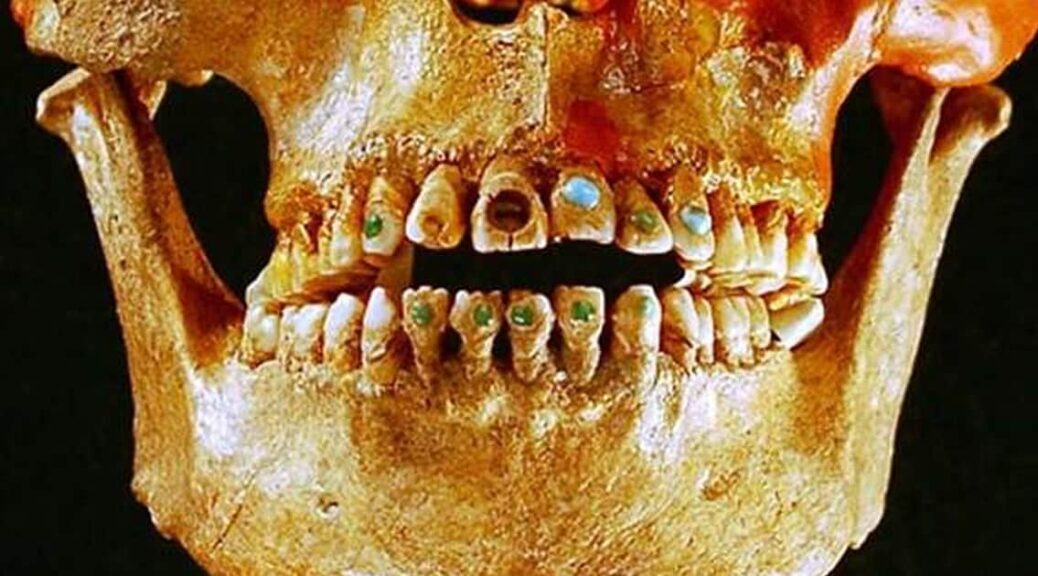

Archaeologists in Mexico have recently uncovered a 1,600-year-old skeleton of a woman who had mineral-encrusted teeth and an intentionally elongated skull – evidence that suggests she was part of her society’s upper class.

While it isn’t uncommon for archaeologists to find deformed remains, the new skeleton is one of the most “extreme” ever recorded.

“Her cranium was elongated by being compressed in a ‘very extreme’ manner, a technique commonly used in the southern part of Mesoamerica, not the central region where she was found,” the team said, according to an AFP report.

The team, led by researchers from the National Anthropology and History Institute in Mexico, found the woman in the ancient ruins of Teotihuacan – a pre-Hispanic civilisation that once lay 50 kilometres (30 miles) north of Mexico City, existing between the 1st and 8th century AD before it mysteriously vanished.

The woman, who the researchers have named The Woman of Tlailotlacan after the location she was found inside the ancient city, not only had an elongated skull, but she had her top two teeth encrusted with pyrite stones – a mineral that looks like gold at first glance.

She also had a fake lower tooth made from serpentine – a feature so distinctive, the team says it’s evidence to suggest that she was a foreigner to the ancient city.

The researchers don’t give any details on how these body modifications were performed 1,600-years-ago, or why they were common in the first place.

But based on other cultures, such as the Mayans, artificial cranial deformation was likely done in infancy using bindings to grow the skull outwards, possibly to signal social status.

While very little is known about the woman’s faux-golden grill, researchers from Mexico did find 2,500-year-old Native American remains with gems embedded in their teeth back in 2009.

In that study, the team said that sophisticated dental practices made the modifications possible, though they were likely used purely for decoration and weren’t symbols of class.

“It’s possible some type of [herb-based] anaesthetic was applied prior to drilling to blunt any pain,” team member José Concepción Jiménez, from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, told National Geographic.

It’s also important to note that the current team’s findings have yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, so we will have to take their word on it for now until they can get their report ready for publication.

The Mexican team aren’t the only ones to discover some interesting human remains lately, either. Back in June, researchers from Australia uncovered 700,000-year-old ‘hobbit’ remains on an island in Indonesia.

More recently, just last week, researchers in China what might be a skull bone belonging to Buddha inside a 1,000-year-old shrine in Nanjing, China.

Needless to say, archaeologists all over the world have been quite busy this year, and we can’t wait to see what they uncover next.