Archaeologists discover medieval skeleton with his boots still on in London

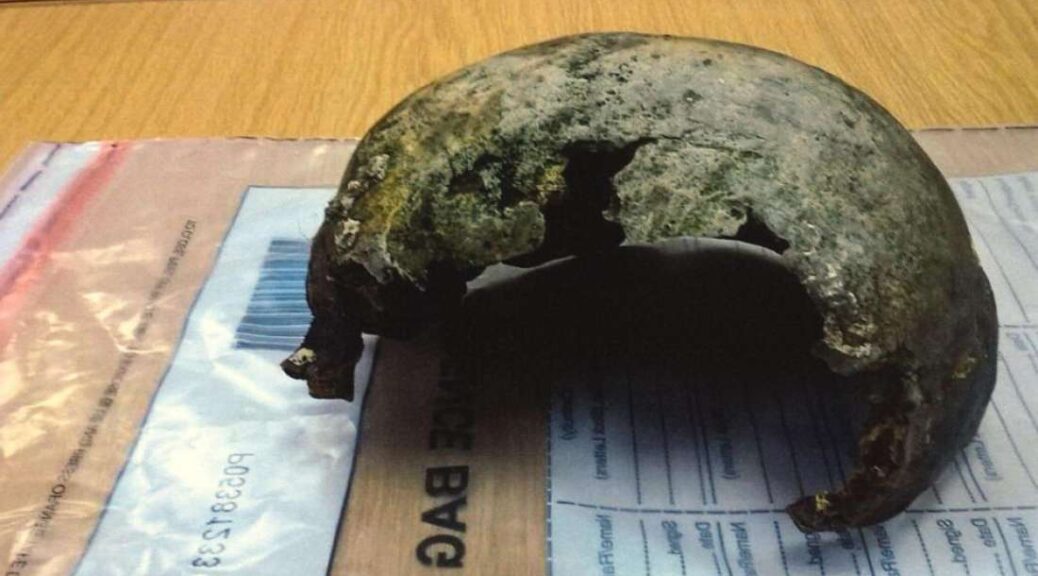

Archaeologists excavating a site along with the Thames Tideway Tunnel—a massive pipeline nicknamed London’s “super sewer”—have revealed the skeleton of a medieval man who literally died with his boots on.

“It’s extremely rare to discover any boots from the late 15th century, let alone a skeleton still wearing them,” says Beth Richardson of the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA).

“And these are very unusual boots for the period—thigh boots, with the tops, turned down. They would have been expensive, and how this man came to own them is a mystery. Were they secondhand? Did he steal them? We don’t know.”

Unearthing skeletons amid major construction projects is not unusual in London, where throughout the centuries land has been reused countless times and many burial grounds have been built over and forgotten. (Learn more about London’s rich history.)

However, archaeologists noticed right away that this skeleton was different.

The position of the body—face down, right arm over the head, left arm bent back on itself—suggests that the man was not deliberately buried. It is also unlikely that he would have been laid to rest in leather boots, which were expensive and highly prized.

In light of those clues, archaeologists believe the man died accidentally and his body was never recuperated, although the cause of death is unclear. Perhaps he fell into the river and could not swim. Or possibly he became trapped in the tidal mud and drowned.

Sailor, fisherman, or “mudlarker”?

500 years ago this stretch of the Thames—2 miles or so downstream from the Tower of London—was a bustling maritime neighbourhood of wharves and warehouses, workshops and taverns.

The river was flanked by the Bermondsey Wall, a medieval earthwork about fifteen feet high built to protect riverbank property from tidal surges.

Given the neighbourhood, the booted man may have been a sailor or a fisherman, a possibility reinforced by physical clues.

Pronounced grooves in his teeth may have been caused by repeatedly clenching a rope. Or perhaps he was a “mudlarker,” a slang term for those who scavenge along the Thames muddy shore at low tide.

The man’s wader-like thigh boots would have been ideal for such work.

“We know he was very powerfully built,” says Niamh Carty, an osteologist, or skeletal specialist, at MOLA.

“The muscle attachments on his chest and shoulder are very noticeable. The muscles were built by doing lots of heavy, repetitive work over a long period of time.”

It was work that took a physical toll. Albeit only in his early thirties, the booted man suffered from osteoarthritis, and vertebrae in his back had already begun to fuse as the result of years of bending and lifting.

Wounds to his left hip suggest he walked with a limp, and his nose had been broken at least once. There is evidence of blunt force trauma on his forehead that had healed before he died.

“He did not have an easy life,” says Carty. “Early thirties was middle age back then, but even so, his biological age was older.”

The examination is continuing. Isotope investigation will shed light on where the man grew up, whether he was an immigrant or a native Londoner, and what kind of diet he had.

“His family never had any answers or a grave,” says Carty. “What we are doing is an act of remembrance. We’re allowing his story to finally be told.”