The ancient helmet was worn by a soldier in the Greek-Persian wars found in Israel

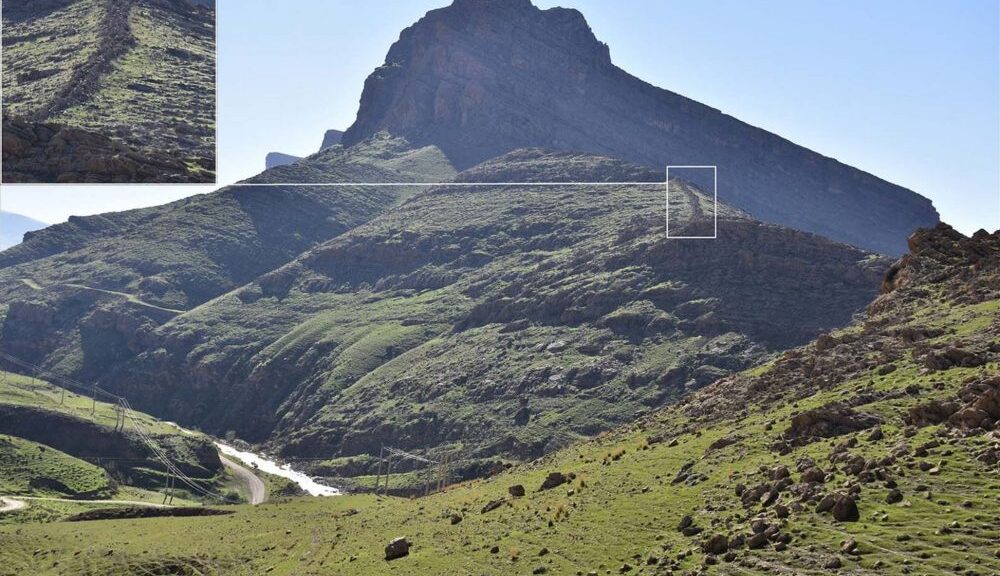

A well-preserved Greek ancient helmet near the Israeli city of Haifa was discovered in 2007 by the crew of a dutch ship crossing the Mediterranean Sea. As required by local law, the dredging vessel’s owner promptly handed the find over to archaeologists from the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA).

Now, reports the Greek City Times, researchers have offered new insights on the object, which is the only intact helmet of its kind found along Israel’s coast.

Crafted in the sixth century B.C., the Corinthian armour was likely used during the Persian Wars, which pitted Greek city-states against the Persian Empire in a series of clashes between 492 and 449 B.C.

“[It] probably belonged to a Greek warrior stationed on one of the warships of the Greek fleet that participated in the naval conflict against the Persians who ruled the country at the time,” says Kobi Sharvit, director of the IAA’s Marine Archaeology Unit, in a statement.

After spending 2,600 years on the seafloor, the helmet’s cracked surface is heavily rusted. But scholars could still discern a delicate, peacock-like pattern above its eyeholes. This unique design helped archaeologists determine that craftsmen made the armour in the Greek city-state of Corinth.

According to Ancient Origin’s Nathan Falde, metalworkers would have fashioned the piece to fit tightly around the head of a particular person—but not so tightly that it couldn’t be swiftly and safely removed in the heat of battle.

“The helmet was expertly fabricated from a single sheet of bronze by means of heating and hammering,” notes the statement. “This technique made it possible to reduce its weight without diminishing its capacity for protecting the head of a warrior.”

As Owen Jarus wrote for Live Science in 2012, archaeologists excavated a similar helmet near the Italian island of Giglio, which is about 1,500 miles from where the crew found the recently analyzed artefact, during the 1950s.

That headgear—also around 2,600 years old—helped modern scholars determine when craftspeople manufactured the Haifa Bay armour.

Experts speculate that the headpiece’s owner was a wealthy individual, as most soldiers wouldn’t have been able to afford such elaborate gear.

“The gilding and figural ornaments make this one of the most ornate pieces of early Greek armour discovered,” wrote Sharvit and scholar John Hale in a research summary quoted by UPI.

One theory raised by researchers speculates that the helmet belonged to a mercenary who fought alongside the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II, per the Express’ Sebastian Kettley.

Another explanation posits that a Greek soldier stationed in the Mediterranean donned the headpiece, only to drop it into the water or lose it when his ship sank.

Though archaeologists aren’t sure exactly who owned the artefact, they do know that the warrior sailed the seas at a time when Persia controlled much of the Middle East.

As Live Science’s Jarus explains in a more recent article, the Persians attempted to invade Greece around 490 B.C. but were defeated near Athens during the Battle of Marathon.

A second attack by the Persians culminated in the Battle of Thermopylae, which saw a heavily outnumbered group of Spartans led by King Leonidas mount a doomed last stand against Xerxes’ Persian forces. (The 480 B.C. clash is heavily dramatized in the film 300.) But while Thermopylae ended in a Greek loss, the tides of war soon turned, with the Greeks forcing the Persians out of the region the following year.

In the decades after the Persians’ failed invasions, the Greek military continued the fight by campaigning against enemy troops stationed in the eastern Mediterranean.

Ancient Origins notes that the helmet’s owner was likely active during this later phase of the war—“when the Persians were often on the defensive” rather than offensive—and may have served on either a patrol ship or a battleship.