Island in the Clouds: Is Mount Roraima Really A ‘Lost World’ Where Dinosaurs May Still Exist?

Deep within the rainforests of Venezuela, a series of plateaus sit more than 9000 feet (2743 meters) above sea level and rise up 1310 feet (400 m) from the surrounding terrain like table tops. From above, they look like islands in the sky.

These are the tepuis (a Pemón Indian word for mountain), the most famous of which is called Mount Roraima. The tepuis are so unique in their geography that thousands of plant species exist nowhere else on the planet except on these plateaus.

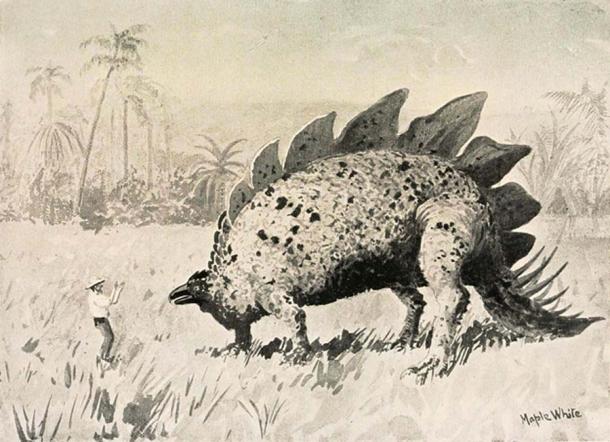

The mystical mountains fascinated explorers and writers for centuries, most notably Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who described an ascent of Mount Roraima in his 1912 novel The Lost World .

In Doyle’s novel, a group of explorers found that dinosaurs and other extinct creatures were still alive and well on the remote plateaus. Some people today still believe this to be a real possibility.

The Real Lost World

Once impenetrable to all but the Pemón indigenous people, Mount Roraima really was a lost world. The mountain plateaus were already established when South America was linked with Africa to form the supercontinent Gondwana, meaning they were first formed perhaps 400 to 250 million years ago.

During this time, molten rock forced its way up through cracks in the sandstone landmass. At the same time, wind and water swept across Gondwana to erode the raised highlands into mountain ranges. The region would come to look much like it does now around 20 million years ago.

Because the tepuis have been isolated for so long atop their high, lonely plateaus, the flora and fauna of the tepuis provide an organic illustration of the processes of evolution.

It is guessed that “at least half of the estimated 10,000 plant species here are unique to tepuis and surrounding lowlands. New species are still being discovered.” (George, 1989).

Although all of the tepuis have been climbed, only a few have been extensively explored. Could this mean that supposedly extinct species, even dinosaurs, may still exist atop these remote plateaus?

Could the Legends be Real?

The Roraima plateaus are so remote and so unique that it is not difficult to imagine Sir Arthur Conan Doyle creating a world alive with prehistoric plants and dinosaurs in his novel The Lost World . Doyle was fascinated with the accounts of British botanist Everard Im Thurn, who climbed to the top of Mount Roraima in December 1884.

Ascending Mount Roraima in 1989 for the National Geographic Society, German explorer Uwe George said, “None of us who followed Im Thurn to Roraima have found primordial creatures or their fossil remains there, but the terrain is so difficult that only a fraction of the tepui’s 44 square miles has so far been explored” (George, 1989). Since his writing, more of Mount Roraima has been investigated and, unsurprisingly, no traces of dinosaurs have been found.

Sacred Ground

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the natives of Venezuela viewed the tepuis as having special mythical significance. According to the Pemón Indians, Mount Roraima is “the stump of a mighty tree that once held all the fruits and tuberous vegetables in the world,” however it was “felled by one of their ancestors, the tree crashed to the ground, unleashing a terrible flood” (Naeem, 2011). They believed that if a person ascended to the top of the tepuis, he or she would not come back alive.

A ‘Crystal Mountain Covered with Diamonds and Waterfalls’

Climbing the tepuis is exceedingly difficult and is made all the more so by the frequent rains that make the rocky footpaths slippery and muddy. The first European explorer to write about the tepuis was Sir Walter Raleigh in 1595. He wrote of a crystal mountain covered with diamonds and waterfalls.

There is a good chance that Sir Raleigh was describing Angel Falls, so named for the mid-20th century American Jimmie Angel who was the first person to fly over the area. Angel Falls were recently featured in Disney’s Up, where the falls are referred to as Paradise Falls.

There is a good chance that Sir Raleigh was describing Angel Falls, so named for the mid-20th century American Jimmie Angel who was the first person to fly over the area. Angel Falls were recently featured in Disney’s Up, where the falls are referred to as Paradise Falls.