Early 20th-Century Ships Spotted in Lake Superior

Michigan researchers have found the wreckage of two ships that disappeared into Lake Superior in 1914 and hope the discovery will lead them to a third that sank at the same time, killing nearly 30 people aboard the trio of lumber-shipping vessels.

The Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society announced the discoveries this month after confirming details with other researchers. Ric Mixter, a board member of the society and a maritime historian, called witnessing the discoveries “a career highlight.”

“It not only solved a chapter in the nation’s darkest day in lumber history, but also showcased a team of historians who have dedicated their lives towards making sure these stories aren’t forgotten,” Mixter said.

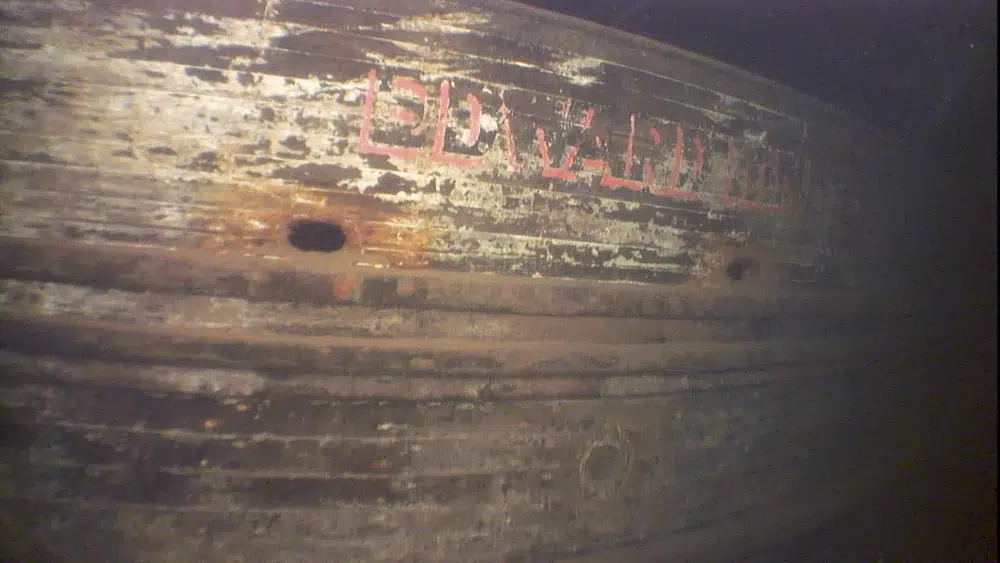

The vessels owned by the Edward Hines Lumber Company sank into the ice-cold lake on Nov. 18, 1914, when a storm swept through as they moved lumber from Baraga, Michigan, to Tonawanda, New York. The steamship C.F. Curtis was towing the schooner barges Selden E. Marvin and Annie M. Peterson; all 28 people aboard were killed.

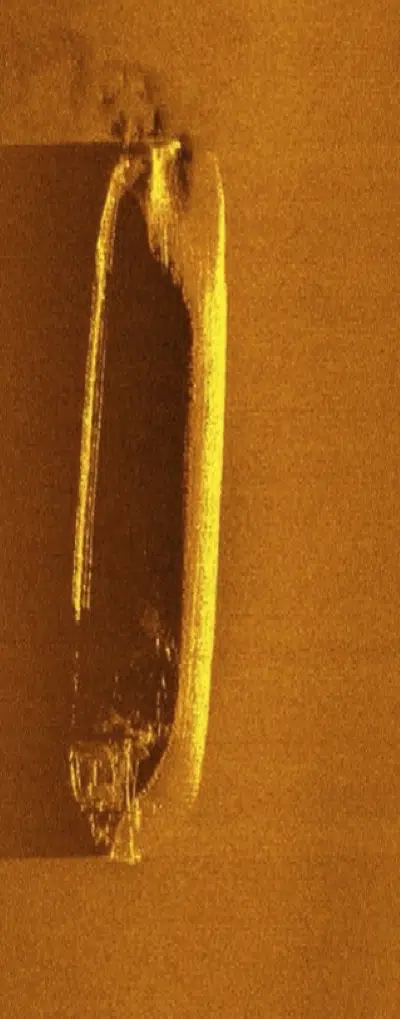

The society’s team found the wreck of the Curtis during the summer of 2021 and the Marvin a year later within a few miles of the first discovery. The organization operates a museum in Whitefish Point and regularly runs searches for shipwrecks, aiming to tell “the lost history of all the Great Lakes” with a focus on Lake Superior, said Corey Adkins, the society’s content and communications director.

“One of the things that makes us proud when we discover these things is helping piece the puzzle together of what happened to these 28 people,” Adkins said. “It’s been 109 years, but maybe there are still some family members that want to know what happened. We’re able to start answering those questions.”

Both wrecks were discovered about 20 miles (32 kilometers) north of Grand Marais, Michigan, farther into the lake than the 1914 accounts suggested the ships sank, Adkins said.

There was also damage to the Marvin’s bow and the Curtis’ stern, making researchers wonder whether a collision contributed, he said.

“Those are all questions we want to consider when we go back out this summer,” Adkins said.

Video footage from the Curtis wreckage showed the maintained hull of the steamship, its wheel, anchor, boiler and still shining gauges — all preserved by Lake Superior’s cold waters, along with other artifacts.

Another recording captured the team’s jubilant cheers as the words “Selden E. Marvin” on the hull came into clear view for the first time on a video feed shot by an underwater drone at the barge wreck site.

“We’re the first human eyes to see it since 1914, since World War I,” one team member mused.